Learn A Valuable Lesson About Storytelling From Hayao Miyazaki

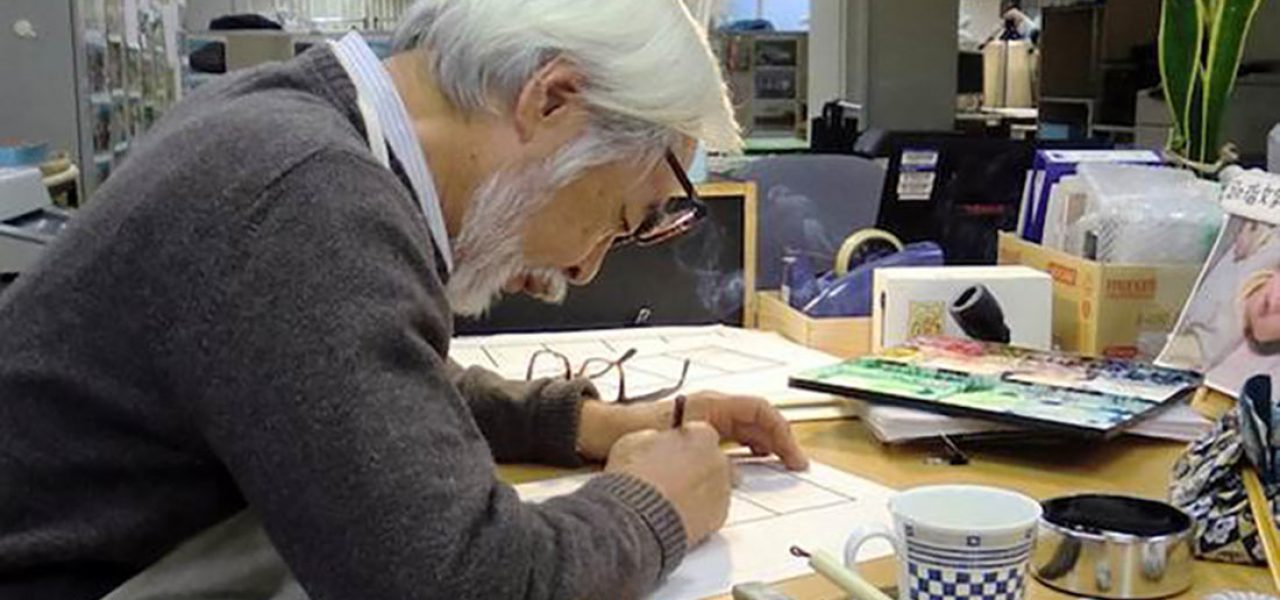

Japan’s most revered animation filmmaker of all time, Hayao Miyazaki, was born on this day, January 5, in 1941. And at age 76, he’s showing no signs of slowing down: he recently threatened to un-retire and make another feature film.

In honor of his birthday, you can read below a brief but inspiring excerpt from the anthology book Starting Point, 1979-1996, in which Miyazaki describes how to develop an idea for a film.

When Miyazaki wrote this in 1979, he had over a decade of experience working in animation and manga, but hadn’t yet completed his first feature. Over the next four decades, Miyazaki would follow this approach, and the results of his legendary career speak for themselves:

The Idea—the Origin of Everything

Is the starting point of an animated film the time when the project is given the go-ahead and production begins? Is it at that point that you, as the animator, first go over your ideas for that story? No, that isn’t the starting point. Everything begins much earlier, perhaps before you even think of becoming an animator. The stories and original works—even initial project planning—are only triggers.

Inspired by that trigger, what rushes forth from inside you is the world you have already drawn inside yourself, the many landscapes you have stored up, the thoughts and feelings that seek expression.

When people speak of a beautiful sunset, do they hurriedly riffle through a book of photographs of sunsets or go in search of a sunset? No, you speak about the sunset by drawing on the many sunsets stored inside you—feelings deeply etched in the folds of your consciousness of the sunset you saw while carried on your mother’s back so long ago that the memory is nearly a dream; or the sunset-washed landscape you saw when, for the first time in your life, you were enchanted by the scene around you; or the sunsets you witnessed that were wrapped in loneliness, anguish, or warmth.

You who want to become animators already have a lot of material for the stories you want to tell, the feelings you want to express, and the imaginary worlds you want to bring alive. At times these may be borrowed from a dream someone related, a fantasy, or an embarrassingly self-involved interior life. But everyone moves forward from this stage. In order for it not to remain merely egotistical, when you tell others about your dream you must turn it into a world unto itself. As you go through the process of sharpening your powers of imagination and technique, the material takes shape. If that shape is amorphous, you can start with a vague yearning. It all begins with having something that you want to express.

Say a project has been decided on and you have been inspired by something. A certain sentiment, a slight sliver of emotion – whatever it is, it must be something you feel drawn to and that you want to depict. It cannot solely be something that others might find amusing, it must be something that you yourself would like to see. It is fine if, at times, the original starting point of a full-length feature film is the image of a girl tilting her head to the side.

From within the confusion of your mind, you start to capture the hazy figure of what you want to express. And then you start to draw. It doesn’t matter if the story isn’t yet complete. The story will follow. Later still the characters take shape. You draw a picture that establishes the underlying tone for a specific world. Of course, what you have drawn will not be your final product. At times, your work may be rejected entirely. When I mentioned earlier that you must have the will to go to any length, this is what I meant. When you draw that first picture, it is only the beginning of an immense journey. This is the start of the preparation stage of the film.

What kind of world, serious or comedic; what degree of distortion; what setting; what climate; what content; what period; whether there is one sun or three; what kinds of characters will appear; what is the main theme…? The answers to all of these questions gradually become clearer as you continue to draw. Don’t just follow a ready-made story. Rather, consider a possible development in the story, or whether a particular kind of character can be added. Make the tree trunk thicker, spread its branches further – or go to the tips of the small branches (this could be the starting point of the idea), and on to the leaves beyond as the branches grow and grow.

Draw many pictures, as many as you can. Eventually a world is created. To create one world means to discard other inconsistent or clashing worlds. If something is very important to you, you can keep it carefully stored in your heart for use at another time. Those who have experienced an outpouring of an amazing number of pictures from inside themselves can feel it. They feel that the fragment of a picture they envisioned, the other trunk of a story that was thrown out while piecing together a narrative, the memory of pining for a girl, the knowledge about a subject gained as they delved deeply into a hobby – all of these play a role and become entwined into one thick strand. The scattered material within you has found its direction and started to flow.

.png)