Hundreds Of Cartoons From 1926 Have Just Become Public Domain

EDITOR’S NOTE: Today, we’re launching a new regular column called Cartoon Study, in which our newest contributor – historian and animator Vincent Alexander – will explore animation from the past, as well as document how classical animation informs and inspires contemporary animation practices. Future articles in the series will be available only to those who have signed up for a Cartoon Brew site account (it’s free and you can sign up by clicking on the CB circle on the right-hand side of page). Without further delay, we’re turning over this exciting historical survey to Vincent…

You may have heard that A.A. Milne’s book Winnie-the-Pooh entered the public domain in the U.S. on January 1, 2022, but Pooh is just the tip of the iceberg for cartoon fans.

Animated films from 1926 are now available for anyone to post, sample, or remix as they see fit. Copyrights can be tricky, so characters featured in these shorts may not be public domain, but the films themselves are up for grabs. There’s also the caveat that these are silent-era films, so added soundtracks may not be free to use. For the purposes of this story, I have used public domain recordings from 1922 and earlier for background music in the clips so they can be shared freely.

I think a lot of people view silent-era cartoons as a footnote in animation history. I’ve certainly made that mistake in the past. But a brief glance over the treasure trove of animation produced in 1926 reveals a level of creativity that is truly staggering.

For starters, take a look at this clip from the hilarious and underrated 1926 Max Fleischer cartoon It’s the Cats (newly restored by Thunderbean Animation) which combines animation, live-action, puppetry, stop-motion, and everything else to create a wacky climax unlike any you’ve ever seen:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

One of the best films of 1926 is the visually stunning fantasy The Adventures of Prince Achmed, the earliest surviving animated feature (released over a decade before Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs). Pioneering female animator Lotte Reiniger crafted the film using silhouette animation techniques that are still inspiring. Just look at the ornate detail of the sets and expressive movements of the shadow puppets, which Reiniger created almost entirely by herself at 24 frames per second:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

Felix the Cat, the first bona fide animated cartoon star, was the most popular cartoon character in the world in 1926. Producer Pat Sullivan took all the credit, but the real genius behind Felix was Otto Messmer, who was anonymously writing, directing, and animating the cartoons that Sullivan put his name to (Messmer also wrote and drew the daily newspaper strip, which Sullivan signed). It was Messmer’s creative personality that gave life to Felix, and his films are full of reality-bending pleasures like this one from Two-Lip Time:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

The other famous cartoon cat of the era was Krazy Kat, loosely based on George Herriman’s comic strip masterpiece. The mid-’20s Krazys were animated by Bill Nolan, who doesn’t get enough love these days considering he created rubber hose animation, which has had a recent resurgence thanks to Cuphead. Just look at the restless, elastic energy in this Bill Nolan scene from Scents and Nonsense (from Tommy José Stathes’ collection):

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

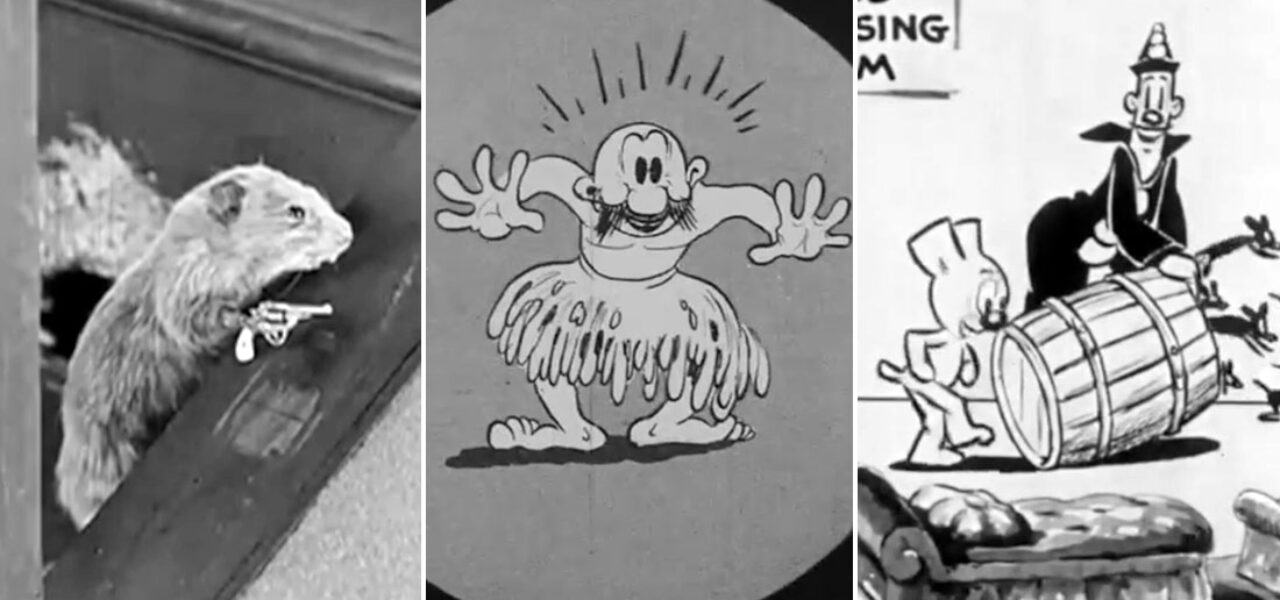

The most inventive cartoons of the 1920s were the Out of the Inkwell shorts from Max Fleischer, who later produced the Betty Boop and Popeye cartoons. The series starred Ko-Ko the Clown and his dog Fitz, who would frequently jump off the drawing board into the real world. The demented finale to the classic Ko-Ko the Convict is a must-see. This thing just keeps topping itself in visual insanity:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

Max Fleischer created the Out of the Inkwell series to show off his invention, the rotoscope, which allowed animation to be traced from live-action footage. By 1926, however, Ko-Ko had been given a heavily caricatured redesign by Dick Huemer and the studio relied less on rotoscoping in favor of wonderful only-in-a-cartoon gags like this one from Ko-Ko Hot After It:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

The Fleischer studio still found special occasions to pull out the old rotoscope, as in this eye-popping bit from Ko-Ko’s Queen. Note that the crew had to build a giant tabletop set just to make this scene work:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

Another series that cleverly combined live-action and animation was Walter Lantz’s Hot Dog cartoons, which began in 1926 and starred Pete the Pup (not to be confused with Lantz’s 1932 creation Pooch the Pup… this will all be on the test). That’s Walter Lantz himself getting blown to kingdom come in this clip from Pete’s Haunted House:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

Walt Disney puzzled a lot of people when he said, as late as 1930, that “my ambition was to be able to make cartoons as good as the Aesop’s Fables series.” Paul Terry’s work is usually considered lower-tier among golden age cartoon fans, but it’s easy to see why his silent Fables were crowd-pleasers. This bit from Hunting in 1950, starring the long-suffering Farmer Al Falfa, is sharper and funnier than many of Terry’s sound films.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

Speaking of Walt Disney, we’re a little way off from Mickey Mouse entering the public domain, but there are plenty of proto-Mickey rodents scampering around in Disney’s Alice Comedies, with Alice’s Brown Derby being a top-notch example:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

Even at this early stage, you can see Disney flirting with a vestigial form of character animation. This great scene from Alice Helps the Romance gets laughs from acting nuances, something Disney would expand on in the 1930s:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

On the flip side, these early Disney cartoons differ slightly from the studio’s later work in their blunt and callous sense of humor. Alice’s Orphan is particularly cynical:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

Some of the silent Disney cartoons are downright morbid. The bizarre Alice’s Mysterious Mystery concerns a dog-killing operation run by cloaked villains that evoke the Ku Klux Klan. The KKK was at the height of its influence in the 1920s, so I wonder what the reaction was to this expressly negative depiction of the group.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

Similarly gruesome is the Mutt and Jeff short Dog Gone, where Jeff dons a dog suit to win some prize money at the dog show (the dumbest and therefore funniest get-rich-quick scheme in film history) and nearly gets ground into sausage links. This is truly sick stuff, but really, really funny. Imagine trying to pitch this to a network today:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

The Mutt and Jeff cartoons, based on Bud Fisher’s comic strip, are sadly underrated, probably because so few survive out of the 292(!) films produced. Playing with Fire delivers one hilarious joke after another, and ends on this all-timer of a sight gag:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

Another incredibly creative joke, from Lots of Water. I don’t recall ever seeing another gag like this in all of the 96 years since this cartoon came out:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

Fleischer veteran Dick Huemer directed the Mutt and Jeff cartoons of the 1925/26 series, and some of the dark imagination of the Fleischer cartoons found its way into the films. The wonderfully spooky Slick Sleuths features a transformative shadowy character named The Phantom, who has so many creative possibilities he could helm his own animated series. Maybe that can still happen now that the film is in the public domain.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

Charley Bowers, a director on the Mutt and Jeff series, might’ve been the first animator to make the switch to live-action filmmaking. His jaw-dropping films, which he wrote, directed, and starred in, combine Chaplin-esque slapstick with crazy stop-motion effects to create surreal visual fireworks. This guy was way ahead of his time, as evidenced in Egged On:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

This bit from Charley Bowers’ Now You Tell One seems like it should be a meme:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

The oldest existing clay-animated film (later dubbed “claymation” by Will Vinton) is 1926’s Long Live the Bull! by Chinese-American animator Joseph Sunn. This series was called Ralph Wolfe’s Mud Stuff, suggesting that the figures were supposed to look like mud come to life:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

For anime fans, A Story of Tobacco is a fascinating early Japanese animated short by Noburō Ōfuji, which takes a cue from the Out of the Inkwell cartoons, only using paper cut-outs instead of traditional cel animation:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

And outside of traditional narrative film, German artist Hans Richter was one of the first to experiment with abstract animation. His 1926 film Filmstudie uses mixed media to create a bizarre dadaist nightmare with floating eyeballs:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

Watching these 1926 cartoons, it’s interesting to see the larger culture reflected in them. Flappers are an iconic element of the Roaring Twenties, and “vamps” show up all over the place in cartoons of the time, most notably Felix the Cat Busts a Bubble:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

And even though these cartoons are silent, they make it clear they were produced in the Jazz Age. One character does the Charleston in Disney’s Alice Helps the Romance, a dance craze that was at the height of its popularity in 1926:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

In some cases, details pop up that you wouldn’t expect to see in films this old. I certainly wasn’t prepared to see the word “swag” show up in Felix the Cat Hunts the Hunter:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 13, 2022

To finish things off, here’s the spectacular grand finale to Koko’s Toot Toot. I hope this article inspired you to play around with or just watch cartoons from 1926. There’s a lot of great stuff to discover.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) January 14, 2022

Some of the restorations featured here are by Steve Stanchfield at Thunderbean Animation, Tommy José Stathes of the Stathes Archive, and maxfleischercartoons.com.