What Did Israeli Animators Do For Summer Vacation? They Saved Their Animation Industry

Heading home from this year’s Annecy Festival, animators and Israeli Animation Guild representatives Ben Molina and Ayala Sharot were on a high.

They’d spent a week making contacts, seeing films, and promoting the Israeli animation community. When they returned home, even better news was waiting for them: after years of discussion, the Israeli government was finally going to announce a pilot tax credit system for the film industry.

“The government came up with this new plan of subsidizing foreign productions that come to film in Israel,” Sharot told Cartoon Brew. “The idea was to give 30% cash back on all foreign investment coming in.”

This initiative, spearheaded by the Ministries of Culture and Sport, Foreign Affairs, Tourism, Economy and Industry, and Finance, was not unlike tax credit systems in many other countries. It was a way to encourage foreign productions and tourism in a country where security concerns and bureaucracy have frequently hindered the film industry.

When the program was finally ready to be officially announced in late June 2022, Molina and Sharot were stunned by the details of the plan: animation had been excluded.

Animation getting the short shift is nothing new. One would be hard-pressed to find a corner of the world where animation is treated on par with its live-action peers. Still, Molina, manager of the Israeli Animation Guild, and Sharot, the Guild chairwoman, were shocked and angered by the government’s erasure of animation from its plans.

“In like two words, they erased our entire industry and essence,” said Molina. “We were pissed. The Guild jumped right into battle. We sent an email to all the Guild members saying this was a red alert and an animation emergency.”

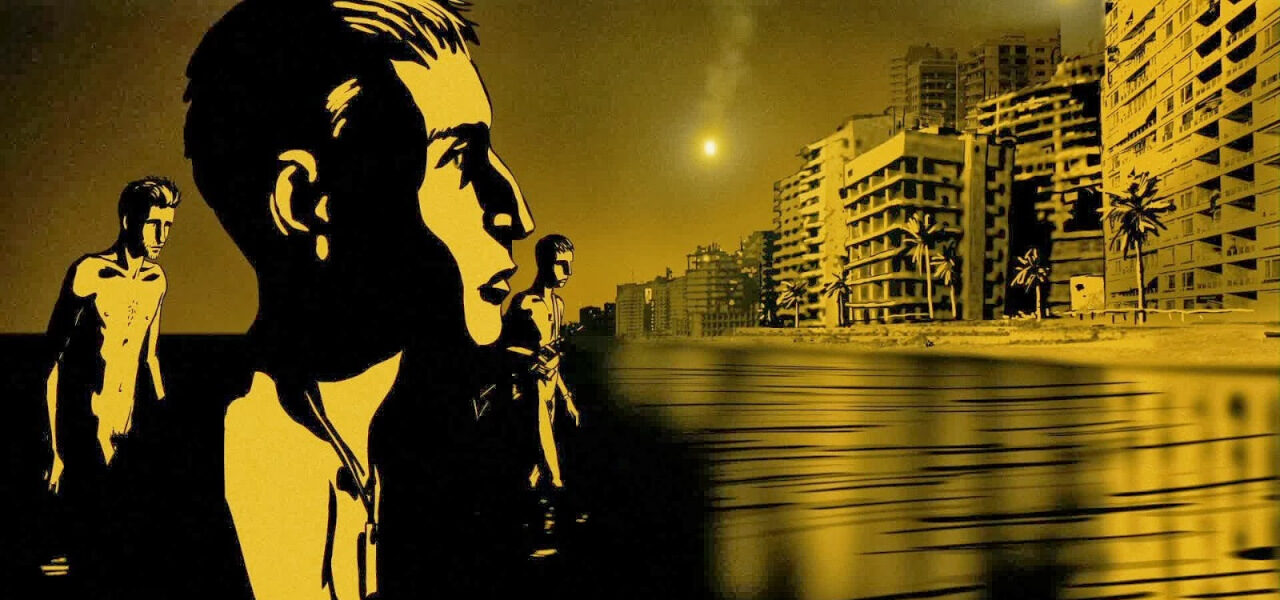

Molina and his associates made phone calls and sent emails to the relevant ministries. They called on union and guild members to send letters to the five ministries responsible for the program. After that, “we approached studio owners, independent animators, teachers, and even the big shots like Ari Folman [Waltz with Bashir], Etgar Keret [A Brief History of Us], and Gidi Dar [Legend of Destruction]. We also managed to get the director, screenwriters, and producer guilds to sign a petition,” he explained.

“As soon as people realized what we were doing, they just volunteered to help,” added Sharot. “One of our community members — a brilliant director and a mother of two children — spent a whole weekend at her computer collecting data, making phone calls to studio owners, and then creating this fantastic document for us. Everyone did their own little part, and it really brought the community together. ”

Once they had their petitions and data, they approached the various ministries. First up was the Ministry of Culture and Sport, who quickly realized that they’d made a mistake and threw their full support behind having animation included in the legislation.

In relatively rapid succession the Guild managed, with the help of the Ministry of Culture and Sport, to get Tourism, Economy, and Foreign Affairs on board. That left Finance. They were not as easily convinced of animation’s economic relevance.

“There were a lot of internal debates,” recalled Molina. “It’s crazy. I believe it’s the first time that the ministries talked with each other about animation. I think that’s an incredible achievement on its own.”

“Governments talked about cinema but never about animation,” Sharot agreed. “That’s the same everywhere. We were like, ‘Hey guys, there’s an industry here and it’s art and it’s economics and it’s good publicity for Israel.”

Sharot believes the government’s definition of cinema is out of date. “The tax credit initiative was started as a way to promote tourism to Israel. If foreign productions came to Israel, [audiences] would see the beautiful landscapes of Israel and maybe come to visit. Of course, you can’t really achieve that in animation. So our case was that film production is different today from, say, the 1980s. You film on greenscreens and use visual effects.”

Furthering the economic argument, Molina pointed out that, “We saw that a production could employ 30 full-time animators for an entire year. With cinema, it’s maybe a few months of shooting and editing, and then you’re done and people go back to the market. So, animation has more potential for creating a stable industry.”

While appealing to the various ministries, Molina and Sharot were constantly frustrated by the unwillingness of organizations to provide any type of explanation for animation’s omission.

“When they ruled out animation, they had no explanation,” said Molina. “It seemed like there was something else going on behind the scenes. Someone seems to have asked specifically that animation not be included, and we just don’t understand why.”

In many countries, there are often internal battles between the live action, documentary, and animation industries. There’s a relatively small pie available to the cinematic arts, and rather than share it equitably, there’s usually some group who wants a larger piece.

In late July, just as the Guild was preparing to file a lawsuit, they got a call from the Ministry of Culture telling them to be patient, and that good news was on the way.

The Ministry of Finance had had a change of heart. At the end of July, it was announced that animation would now be included in the new tax credit system. Exhausted, stressed, and emotionally spent, Molina and Sharot were, more than anything, ecstatic.

The entire process proved a revelation.

“The most beautiful thing was that it brought the animation community together,” said Sharot. “People are starting to understand that it’s an ecosystem that feeds off each other. It’s not just one studio that can make it. You need everyone. That’s the only way to make the industry grow.”

The experience was also a hasty initiation for Molina and Sharot into the messy world of politics. “We started to understand that we have to be politicians,” said Molina. “We have to have representation.”

Or as Sharot puts its, “Sometimes an artist has to learn to be a politician.”