Brenda Banks, One Of The First Black Women Animators In America, Dies At 72

Brenda Banks, who has died aged 72, blazed a quiet trail through the animation world, building up an impressive résumé in an industry where few Black women had succeeded before. As an animator, she worked with directors such as Ralph Bakshi — who claimed, erroneously, to have discovered her — and on iconic characters like the Looney Tunes and The Simpsons. Known as a private person, Banks shied away from the spotlight, but her talent spoke for itself.

Although Banks passed away on December 31, 2020, the industry is only now learning of her death. This is largely thanks to historian and animator Tom Sito, who shared the news via Facebook, noting that he’d learned of her passing through the Animation Guild. It’s in this post — particularly the comments left by others — that we are now seeing a much clearer picture of the artist Banks was.

Decades of Experience

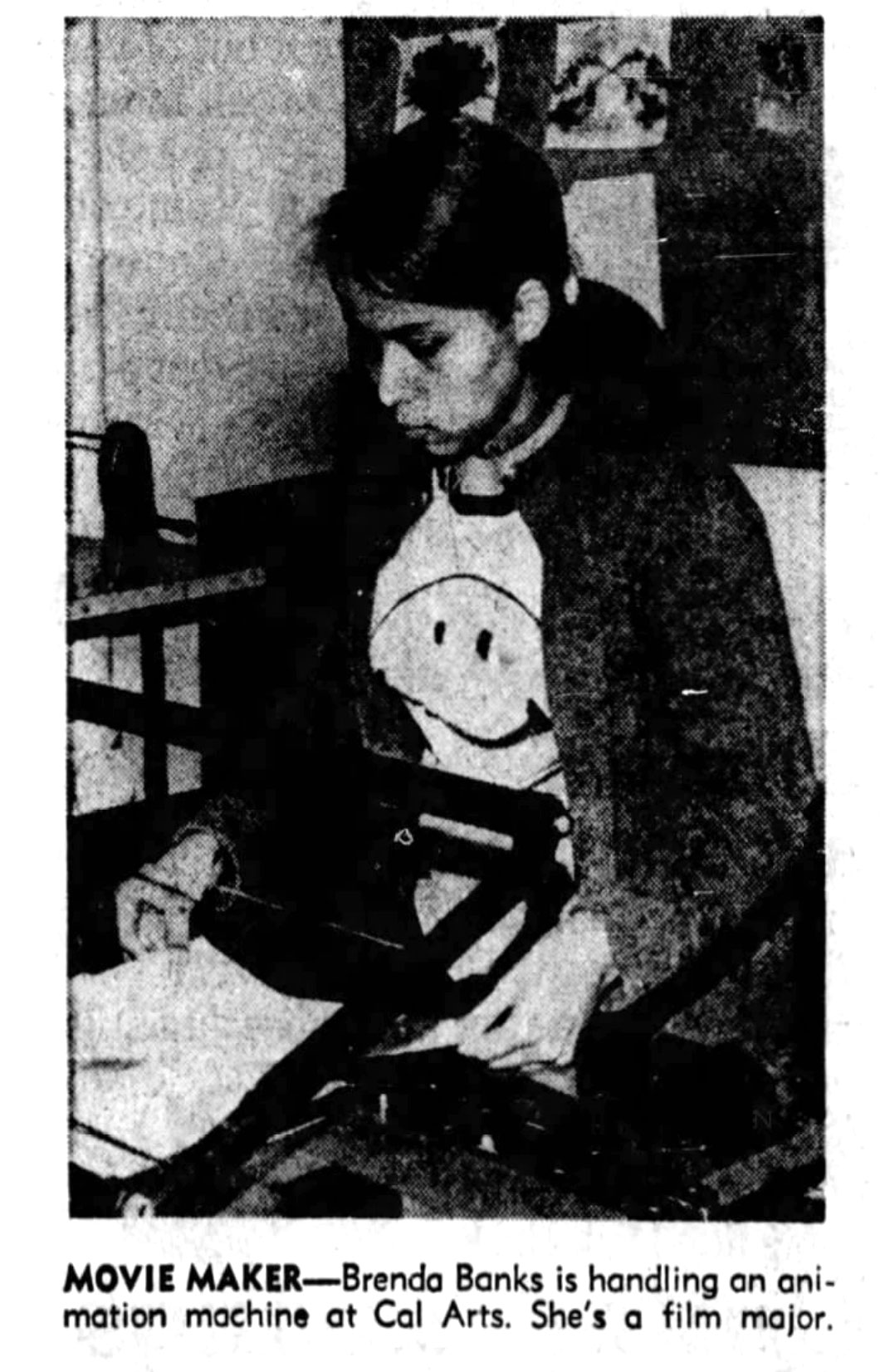

Brenda Lee Banks was born in Los Angeles on July 19, 1948. She graduated from Fremont High School in L.A. in 1967 then attended California Institute of the Arts. The exact timeline of her attendance remains unclear, but this photo in the Los Angeles Times confirms that she was there in 1972. Fellow artists commenting on Sito’s post recall her being there even in the late-1960s (when the art school was known as Chouinard and located in Los Angeles) and as late as 1977.

Banks’s early credits include working as an animator on Flip Wilson’s tv specials, produced at DePatie-Freleng Enterprises in 1972 and 1974. Bakshi would later claim that she had walked into his studio one day, saying she had never animated and asking for a job. Her credit as an animator on the Flip Wilson specials make clear that she had already broken into the industry by the time Bakshi found her.

Bakshi hired Banks for his 1974 film Coonskin, on which she worked uncredited. She subsequently worked on the director’s Wizards (1977), Lord of the Rings (1978), American Pop (1981), Hey Good Lookin’ (1982), and finally Fire and Ice (1983), where she was described as a veteran guiding the rookies in the biography Unfiltered: The Complete Ralph Bakshi by Jon M. Gibson and Chris McDonnell.

In his book Forbidden Animation: Censored Cartoons and Blacklisted Animators in America, Karl F. Cohen gives some context Banks’s work with Bakshi, quoting a 1982 Village Voice article by Carol Cooper:

… Bakshi had trained about ten black animators to work on Coonskin and Hey Good Lookin’ at a time when there were no black animators working at Disney. Apparently there never had been any at Disney, and there were very few elsewhere in the animation industry … when [Bakshi] made Wizards he hired Brenda Banks, “for a time the only black female animator working in Hollywood.”

It wasn’t the case that there were no Black animators at Disney — Floyd Norman began there in 1956 and others like Ron Husband and Phil Mendez worked in either animation or Imagineering in the 1970s — but the fact remains that there were few Black artists in these spaces.

In between these films and afterwards, Banks worked on several series and tv movies, such as the Dr. Seuss special The Hoober-Bloob Highway (1975). She also worked on iconic characters like Heathcliff, The Smurfs, Scooby-Doo, Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck, Charlie Brown, and the Jetsons, among many others. Someone on Facebook recalled working with her at the now-defunct Vortex Media Arts on a CD-ROM game of The Simpsons. A few others recalled working with her on the final two seasons of Fox’s King of the Hill, around 2007 and 2008, where she worked in layout. This role was her last known industry job.

Whatever studio she found herself at, be it Hanna-Barbera or Warner Bros., Banks was remembered for her kindness and humor. Many also described her as quiet — shy, even — and immensely talented. She animated well and fast, and often giggled while doing so.

A Silent Force in the Industry

Banks’s name is mentioned in passing in books like Hollywood Heroines: The Most Influential Women in Film History by Laura L. S. Bauer and Drawing the Line: The Untold Story of the Animation Unions from Bosko to Bart Simpson by Tom Sito. She’s listed alongside names like Reiko Okuyama, Retta Scott, Mary Blair, Nancy Beiman, and Linda Simensky. While countless books and articles document these other women, little can be found about Banks.

Beiman commented on Sito’s Facebook post: “I met Brenda when she was in Jules Engels’ program at Cal Arts. Her film involved brilliant caricatures of the Three Stooges as a triple headed dinosaur. Her drawing was spectacular. I recall that she was very shy. I really admired her work at Bakshi’s.” Beiman also recalled Banks having a physical disability, needing leg braces before having surgery.

As a Black woman with a disability, Banks entered the industry with the odds stacked against her success. Animator Lee Crowe, a former colleague, wrote on Facebook that Banks didn’t want to be known for being the (supposed) first Black woman animator.

That’s a sentiment many “firsts” certainly share: not wanting any glory or recognition for having to overcome barriers that shouldn’t have been there in the first place. The sense that glorifying one person can detract from the systemic problems that affect a marginalized group, and that a space can only be truly equitable once diverse voices are normalized. Nevertheless, by acknowledging the accomplishments of these hidden figures, the path for those who follow continues to expand.

No details about Banks’s cause of death or surviving family are available at this time, but we will update the story should that information become available.

Image at top: a crew photo of the animators on Ralph Bakshi’s “The Lord of the Rings” with Banks circled.