The Russian Animated Series ‘Jinglekids’ Aims For Ambitious Visuals With A Small Team

You may have noticed the Russian-made animated children’s series Jinglekids (Jingliks) is now available on Netflix. And you might also have taken note of the high quality of animation in the show, which is produced by Open Alliance Media.

JingleKids is set in Jingle City, where humans characters and furry creatures go through a number of adventures together. The series was adapted from the original children’s books (called Jingliks).

Getting to the desired level of quality for the show involved several leaps and bounds from showrunner and director Anton Vereschagin, who shared with Cartoon Brew the technical and structural challenges of making an animated series in Russia.

A brief history of the show

Vereschagin took on director, showrunner, art lead and production supervisor roles, and also dove into 3d production itself while getting Jinglekids up and running. “After we produced the first four episodes,” he said, “Disney Russia acquired exclusive tv rights for the series for almost two years. Then there was a series of sales worldwide, then the show came to China on VOD platform Tencent, and in April Jinglekids came onto Netflix in 190 countries around the world.”

Production began with a small team in Saint Petersburg, before being sold to Open Alliance, which then started Open Alliance Media to produce the series.

For Vereschagin, that meant not only moving forward with the show, but also setting up an entire studio, building a pipeline, and hiring a team. “For the first couple of months there were just a few of us. We never had enough people. At maximum, we had 40 people working on the show regularly, although we had a lot of freelance animators from all over the world, too.”

Setting up an animation pipeline

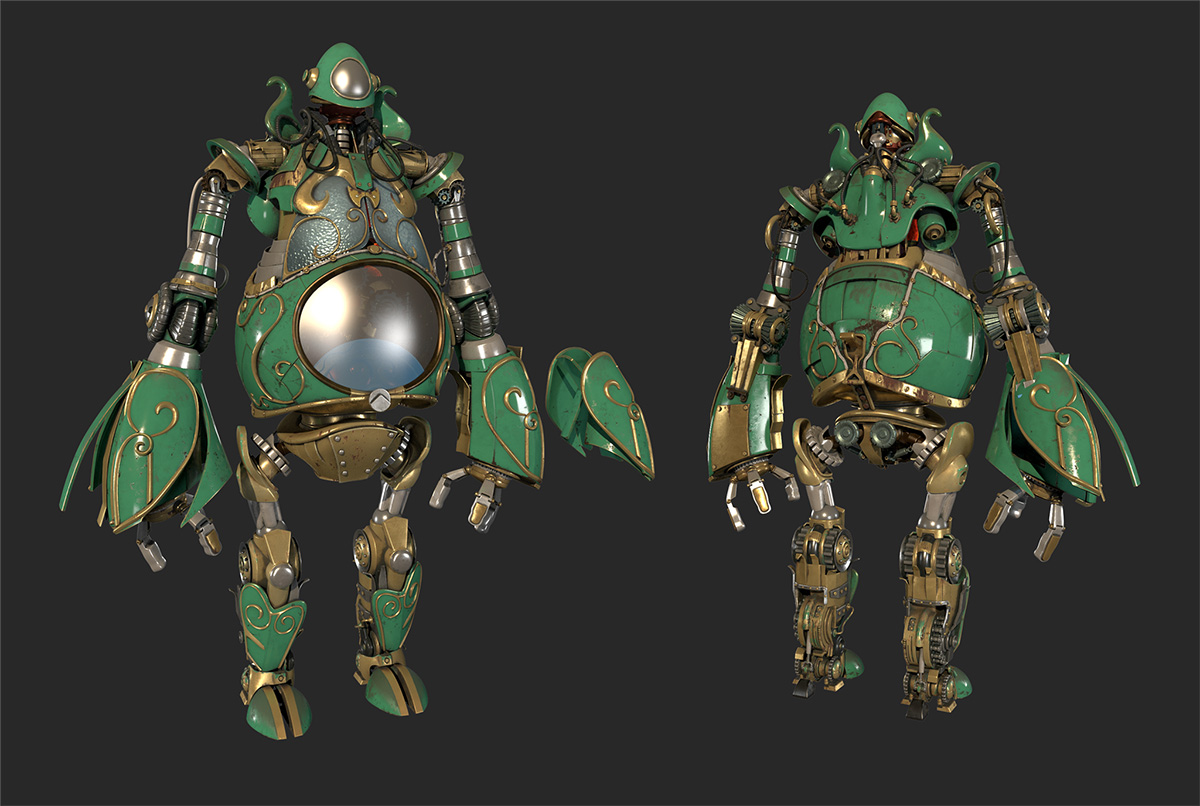

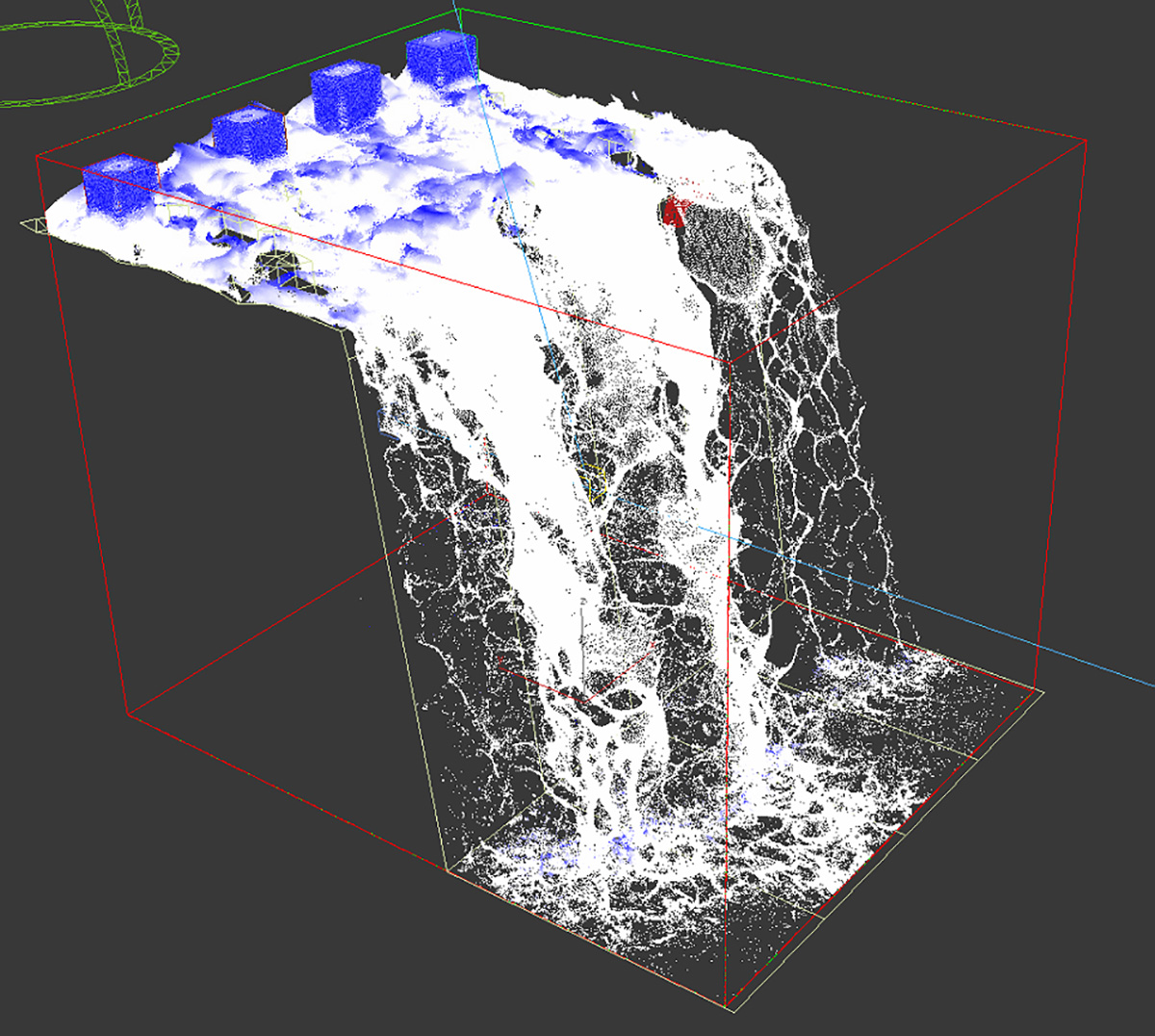

The main tool at the disposal of the team for animation was Autodesk’s Maya. Pixologic’s Zbrush was utilized for sculpting, with both Foundry’s Mari and Allegorithmic’s Substance used for texturing. Peregrine Labs’ Yeti enabled hair and fur simulations, Chaos Group’s Phoenix for FX sims, V-Ray for rendering, and Nuke for compositing. From a project management point of view, Shotgun provided shot management and Thinkbox’s Deadline was used for render management.

In many ways, that is a very standard pipeline for animation and visual effects. But Vereschagin notes, in particular, that it was the adoption of V-Ray that allowed his small team to complete the ambitious work. “First, I was afraid. At that time V-Ray wasn’t that popular in animation production and I was in the middle of production of the first pilot episode. But I decided to take the risk of dramatically changing the pipeline and now I think it was one of the best decisions I’ve made on the project. I finally got what I wanted – an out-of-the-box solution — you just take it and use it, a newcomer can figure out how to use it in two weeks.”

“We met the guys from Chaos Group,” added Vereschagin, “and they gave us 50 licenses for render nodes and four licenses for four months of workstations for free and guaranteed ultra support. I hired a render TD, Pavel Igumnov, who was a V-Ray beta tester and we started to use the new renderer. By the end of production of the pilot episode, Chaos Group provided V-Ray with almost all the functions we needed. Our V-Ray experience and quality of the imagery inspired a few studios in Russia to use V-Ray as well.”

Tech challenges

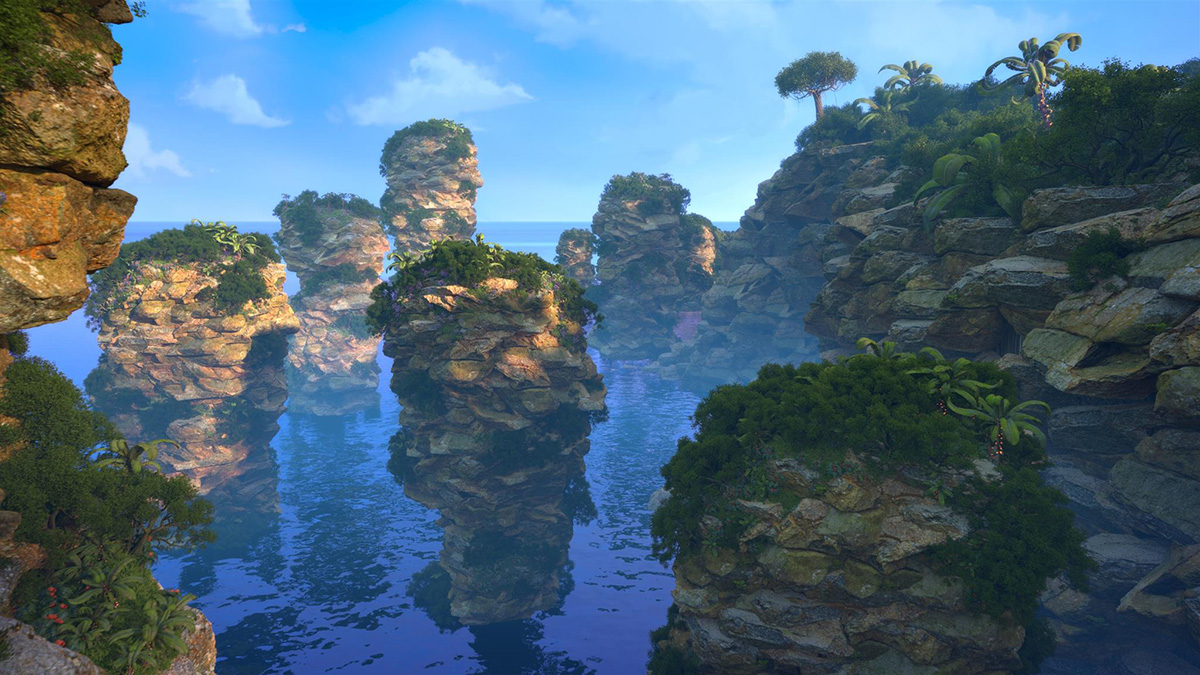

Despite the positive experience with V-Ray, the production on Jinglekids still faced a few uphill battles in reaching the level of quality they were after. One was render times. “Sometimes one frame would take 10 hours to render because of a very heavy and detailed environments,” said Vereschagin. “Or there’d be an inability to optimize the scene and some scenes wouldn’t even make it to the ‘blade’ memory. Rendering didn’t have all the functions we needed right away, and on the pilot we did face a lot of problems.”

Later, the team was able to bring render times down to 40 minutes per frame for full HD and two hours per frame for 4K scenes, but it was tough at the very beginning to make things work efficiently. “If you take a closer look to the intro to the show, you’d notice it has noise,” admitted Vereschagin. “Flying over Jingle City was a great idea, but the scene was incredibly heavy so we couldn’t avoid noise while rendering. And due to the delivery schedule, I decided to leave it the way it is. Unfortunately, I’ve never had the resources to re-render it and make it as awesome as it should’ve been.”

There were other challenges, too, as the production journey continued. Vereschagin did not initially like the way that rocks in the show looked, even though sculpting them in cg was taking some time. “So starting in the tenth episode we tried using 3d scans instead and it was a great decision – we could make a rock build in a day.”

Further hurdles were mostly about the time taken to complete modeling or simulations. For example, character rigs were at first too complicated, and so later were simplified. Wind was simulated for much of the natural environment, but this proved too time consuming, and was later built only into leaves on trees, ignoring the impact on grass and bushes. Dynamics in character fur and hair was also kept simple.

Production in Russia

If technological pressures on a new team as the show ramped up weren’t challenging enough, Vereschagin suggested that finding the right talent in Russia was another obstacle. “Until the last few years, we didn’t have any courses or universities where you could specifically study computer graphics. You could get a director’s degree, an artist degree, but nothing with a narrow specialization.

“Most of the industry pros are self-taught,” he continued. “At the same time, the number of projects has gone up dramatically, and studios hunt the talent and in Russia you can’t obligate someone to work for you for a fixed term – you can’t have a year contract due to the labor regulations, so the studios spend a lot to train people, but no one can stop the people from leaving the studio if they find a more attractive job.”

Still, with Jinglekids, the creators have managed to produce something that does stand out, and now will receive even more worldwide exposure by being on Netflix. It’s a long way from the project’s early beginnings, with Vereschagin accounting its success to the series being very ‘creator-driven.’

“I’ve run it as if I was working on a very personal artistic project,” said Vereschagin. “So did almost every member of our team. Each episode ends with ‘to our children’ and that is what we really mean. Also, every little detail is essential. Even the way the stones are laid out on the bottom of the river. The detail is what makes the universe true.”

.png)