How ‘Ready Player One’ Combined Virtual Production And Motion Capture Tools To Create Digital Characters

Much of Steven Spielberg’s Ready Player One is set in the Oasis, a virtual reality world full of digital avatars, game and film characters, and expansive cg environments. To produce that world, the director relied heavily on a virtual production methodology overseen by Digital Domain where actors were filmed in motion capture volumes and where shots could be designed and tweaked live with a simul-cam or ‘v-cam.’

The result was a template that visual effects studio Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) could then use to bring those digital characters and environments to life for the Oasis. One of the studio’s toughest challenges was translating motion and facial capture from real-life actors to their digital counterparts, especially since the characters inside the Oasis did not necessarily need to appear humanoid or photoreal.

Cartoon Brew looks at the steps involved in Ready Player One’s virtual production paradigm, including the previs, shooting process, and how the motion capture was adapted for digital character translations.

A virtual shoot

Spielberg has of course stepped into the world of virtual production and motion capture before, for the films The Adventures of Tintin and The BFG. In many ways, Ready Player One’s Oasis scenes were handled in similar ways; the actors are filmed wearing motion capture gear in a capture volume. A simul-cam set-up allowed for the filmmakers to frame the actors against proxy cg sets and set-pieces, and to also allow for shots to be ‘virtually’ re-shot afterwards. The motion capture data and the virtual camera data became a template for the final vfx shots.

Leavesden studios in the U.K. was the location for the motion capture shoot. Here, Digital Domain and Audiomotion combined to build a capture volume made up of Vicon motion capture cameras. Spielberg had earlier scouted some of the virtual sets at Digital Domain’s own capture volume in Los Angeles, including with the use of different vr headsets.

Additional capture volumes at Leavesden were built to allow for stunt sequences to be filmed, and a separate vr volume allowed Spielberg to use a simul-cam – essentially a monitor with joysticks he could hold in his hands that was tracked in the volume – to review takes and make shot decisions.

Different vr headsets were also utilized for seeing the virtual worlds while filming motion capture, scouting sets, and even when shooting on practical sets.

On set, the actors wore optical tracking marker suits and facial capture head-cameras, the data from which fed into Motion Builder. When the actors had to interact with props, these tended to be built as simple frames. For example, the main character Parzival (played by Tye Sheridan) drives a virtual Delorean from Back to the Future. In the capture volume, the vehicle was represented as a car frame only, and ultimately realized as a cg car by ILM.

Earlier, The Third Floor and Digital Domain had produced previs for the film. Ready Player One has many grand sequences in the Oasis, which means previs proved to be vital, not only for working out the look and feel of those scenes but also providing for characters and assets used during the motion capture shoot. Digital Domain’s previs was done firstly in Maya and then brought into a Unity game engine system as part of the virtual production pipeline.

“In previs, we were working much more quickly and looser just trying to figure out the story, trying to understand the flow of the sequences,” said Scott Meadows, head of visualization at Digital Domain. “But once things solidified we would then turn that over to a ‘virtual art department,’ which would then validate the assets, and then there were other teams working in Motion Builder that were building master scenes, so that they could shoot with the v-cam.”

One of the many previs sequences Digital Domain worked on was the car chase in New York. Here, Meadows says he felt an initial take on the race wasn’t ‘Speed Racer’ enough, and so in previs he helped amp it up.

“It just needed something that wasn’t possible in the physical world because everything that they had at the time was fairly grounded in reality,” Meadows said. “The idea, too, was that the city was always changing. It wasn’t the same every time. Once we cracked that open as far as these ideas about how this thing could be dynamic, and changing, but that you still recognize it’s New York, that’s when I feel like it really started to shine as a sequence.”

From virtual shoot to virtual character

When it came time for ILM to translate the motion capture into digital characters, the visual effects studio was able to take advantage of earlier work on other virtual production shows, including the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles films and Warcraft.

“The motion capture data will go through layout to start implementing it into the digital characters to get a first pass,” explained ILM animation supervisor Kim Ooi, who led the effort at the studio’s Singapore office, just one of ILM’s locations involved on the film. “From that point on, it’s passed down to the animators to actually do clean up and to enhance if it’s needed, and to really make sure that the body performance and especially the facial is actually true to what the actor’s doing.”

“The trickiest part is actually figuring out how we can actually do the transfer from motion capture data for the face to the digital puppets because the structure of their face and their avatars is slightly different,” added Ooi. “The motion translates, but not really their persona, per se, so we have to do a lot of testing and figuring out to make sure that everything works one to one.”

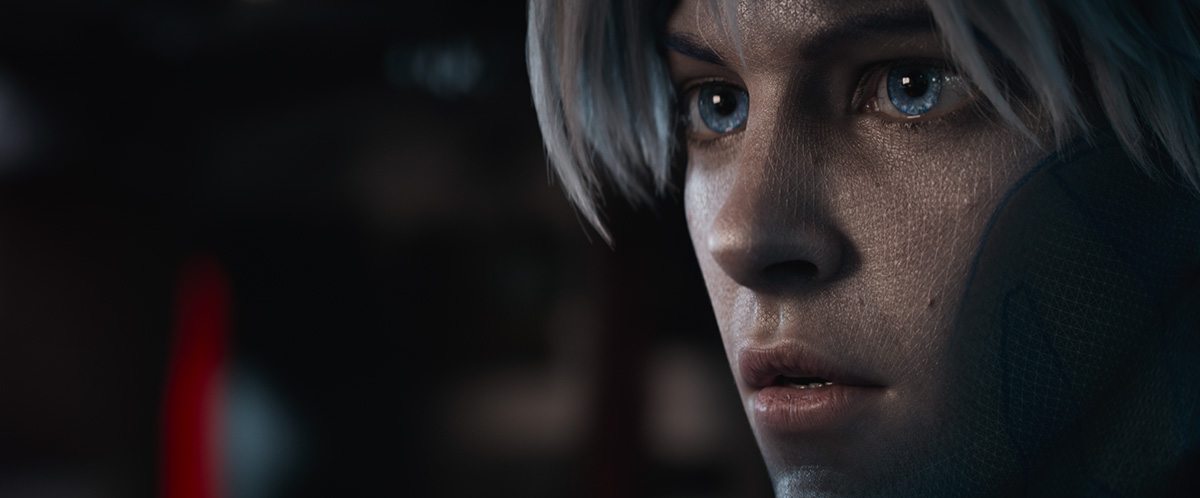

With Parzival, who is designed to appear as a stylized cg human, ILM had to strike a balance between a vr-looking avatar and a character that still had its origins in the appearance of the motion capture actor, who in this case was Sheridan. He and the other actors were scanned via the Medusa Performance Capture system developed by Disney Research to obtain a geometrically correct version of the face, which ILM could then apply to whatever degree necessary to the virtual character.

“A lot of the time we would go kind of back and forth to say, ‘Hey, the motion’s there, but his eyes, it doesn’t feel like Tye Sheridan’s eyes,” said Ooi. “Although they’re not the same eyes, we have to at least get the idea that it’s the same person playing that role.”

Added Ooi, “We went through different design changes on the eyes, definitely on the mouth, on the shape of the face, and then sometimes we veer off a little bit too realistically and then it started becoming, ‘Is this the uncanny valley? Do we really want to do that?’ So then we started going back to more like the avatars that we see right now, more stylized. One thing that we didn’t want to do is make it too realistic because they’re supposed to be living in this game world, and you can do whatever you want, so why be realistic rather than being more stylized?”

In some sequences, ILM would have to combine motion capture performances from principal actors with stunt doubles. An example of this was for actor Lena Waithe’s avatar Aech when the character is involved in some heavy fighting action.

“That was kind of tricky because we’d have the body of a stunt double, but then Lena’s face as a performance capture,” said Ooi. “In the Oasis, it’s not so much we want to have just physical movements – we want to enhance that. Maybe a character would be jumping a lot higher so we’d do an exaggeration in the physiques of the character. And blending all those together in one take, that was quite challenging.”

.png)