The Animation That Changed Me: Hisko Hulsing on ‘Pink Floyd — The Wall’

Hisko Hulsing revisits his adolescence for this week’s edition of The Animation That Changed Me, a series in which leading artists discuss one work of animation that deeply influenced them.

Painter, composer, animator, and director, Hulsing burst onto the scene with his short films Harry Rents a Room, Seventeen, and Junkyard (the last of which won the grand prize at Ottawa Int’l Animation Festival). The Dutch filmmaker is the director and production designer of Undone, Amazon’s first original animated series, and he oversaw the animated segments in Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the documentary portrait of the Nirvana frontman.

Hulsing’s choice is Alan Parker’s 1982 feature Pink Floyd — The Wall, a dramatization of the British rock band’s eponymous concept album. The film combines live action with animated segments, which were directed by the renowned cartoonist Gerald Scarfe. Below, Hulsing talks about what makes the film special for him:

I remember seeing Pink Floyd — The Wall on a videotape during a visit to a pot-smoking friend of my parents. I was immediately overwhelmed by the music and the animation. It drew me right in. Here was an insanely beautiful film that was about me! About my rich adolescent inner life! About the pain and depression and craziness that I felt.

I was fifteen and I was smoking marijuana on a daily basis. I was stoned, I was nervous and depressed, and the pot seemed to change my perception in very dark ways, creating confusing hallucinations and delusions.

The Wall completely romanticized my self-pity and made it all look fantastical, beautiful, and trippy. The animation sequences were even trippier than my own trips!

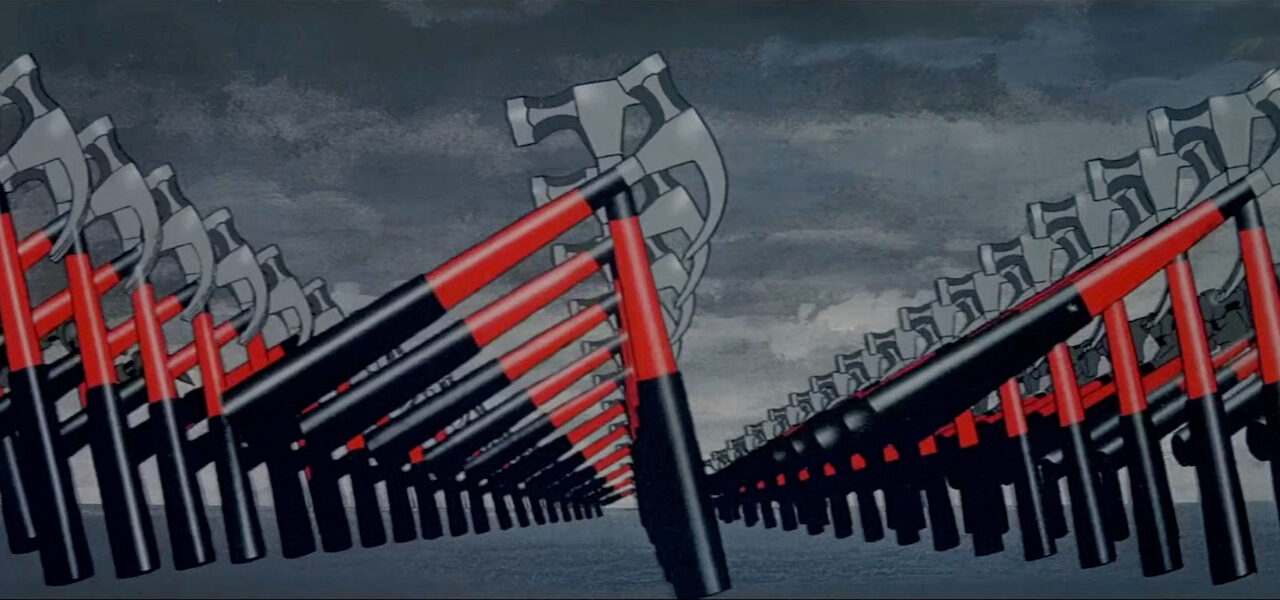

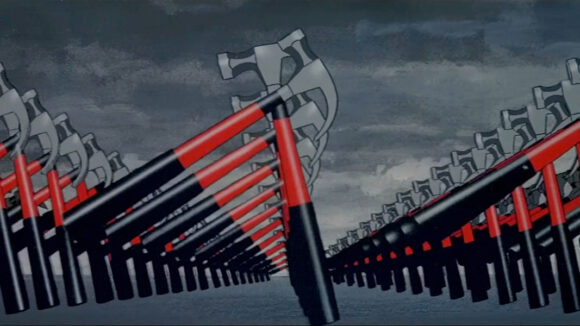

The film also fit very well with my bleak view on life at that time. It contains a great piece of animation which perfectly illustrated how I saw society and school. Faceless students are being squeezed through a meat mincer by a frustrated teacher. That was exactly how I felt: squeezed through a meat mincer by society, to flawlessly fit within the system and be part of a shapeless uniform mass, together with my peers.

In hindsight, I probably felt exactly that way because I had seen The Wall … It’s really hard to know after so many years. Nowadays I have more nuanced world views, no worries. It’s not that bad, folks!

I would say that most animation is made for family entertainment and comedy, probably because animation lends itself so well to very physical humor. But I found out through The Wall, and other animated films, that animation is also an excellent medium for blurring the barriers between dream and reality and showing the inner world of a character.

I used animation to depict psychosis and delusions in my short films Seventeen and Junkyard, and in the Amazon series Undone (with showrunners Kate Purdy and Raphael Bob-Waksberg). In Undone it works in a really strange way, because the actors are rotoscoped. We film the actors first, then trace them and place them in an oil-painted world. The world feels very real, but also unreal, dreamy, and painterly. It is never completely clear to the audience whether we are on a trip in Alma’s head, who might be suffering from schizophrenia, or if we are actually watching reality.

This could not be done without animation. If we had filmed it as a live-action series, there would be a clear distinction between reality and all the weird trippy stuff happening, which would create a clear distance between us and Alma. Our goal was to take the audience on a trip with Alma. See and feel what she sees and feels, through animation.

On Montage of Heck, we realized of course that we were doing something comparable to The Wall, in that we were integrating animation into live action. The difference was that we were trying to capture the inner life of a real person — namely Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain — and not that of a fictional person, as is the case in The Wall.

For Montage of Heck, we had eight minutes of audio on a cassette tape, with sound collages and stories that Kurt Cobain recorded aged 20. The story he told was a typical coming-of-age story, which showed his insecurities, his depression, his marijuana use, his struggles in life, and even his early suicidal thoughts. It seemed to give a very unique insight into his troubled character.

Since it was just audio, director Brett Morgen needed visuals that would both enhance and counter-narrate these fragments. When he saw my film Junkyard, he thought that my grim and realistic animations would complement Kurt Cobain’s character very well. He noticed the same kind of raw energy.

The coming-of-age story that Kurt Cobain told was so similar to my own adolescent past that I felt very comfortable animating it. We couldn’t be too psychedelic, so the animation couldn’t be as wild as The Wall. But our painterly animation definitely feels dreamy and strange and helps the audience to catch a glimpse of Kurt Cobain’s rich, self-pitying inner life, just as The Wall helped us get into the head of Floyd. Almost as in a dream.

I think that The Wall was constructed as an album in the first place, not as a film. Like many pop-song lyrics, [the album’s narrative] is so vague that it is very possible to project all kinds of meanings onto it, and feel all kinds of feelings that might or might not have been intended by the writers. There is nothing wrong with this, and it works for those who are sensitive to all that bombastic visual violence. Like me.

But from a purely narrative point of view, the film often lacks motivation. It could be seen as a series of pretty unrelated slices of life, magically stitched together with the music. There are a lot of story elements that seem like beginnings of thoughts which then never really crystallize: parallels between World War II fights and modern riots, fascist imagery, mass media, and pop concerts. Lots and lots of associations and hardly a real story. But very effective to some audiences!

One of the strange things about The Wall is that it feels like an animated film with some beautiful live-action scenes in between, while it is actually the other way around. There are only 11 minutes of animation in the film. But the animation is used in such an iconic and impressive way that it merges seamlessly.

The Wall played for years as a night show in the cinemas in Amsterdam. I watched it many times. Apparently I like to immerse myself once in a while in the kind of melodramatic self-pity that I felt when I was a 15 year old pothead, and relive it all over again. Why?!

But it is also still very inspiring. The rapper Kid Cudi once invited me to L.A. to spend time in his house and the Hollywood sound studio where he was recording his new album. He loved Montage of Heck and wanted me to make a long, insane videoclip, drenched in LSD. The walls in his house were decorated with pictures from The Wall. There was no way I could escape the thick layer of smoke in his house and the studio. I stopped smoking pot 32 years ago, but his second-hand smoke made me high again. It wasn’t bad, actually…

Kid Cudi and I didn’t really click, so that film never materialized, and he was institutionalized not long after that. However, it did give me a lot of inspiration for a short film that I have completely storyboarded, but that I can’t make right now because of a lack of time. Because of the second season of Undone, actually.

I would describe the short as a mix between Pink Floyd — The Wall, Francisco Goya’s print series “The Disasters of War,” and his “Black Paintings.” Very dark and intense, animated to the fantastic symphonic music of Dmitri Shostakovich. It is my dream project, so it must come true someday!

.png)