The Disney Artists’ Strike of 1941 Changed Animation Forever — And For The Better

The Disney brand is in large part rooted in nostalgia, and the company loves to celebrate historical anniversaries and milestones. Every event — big or small — is acknowledged through the company’s corporate streams, whether it’s the 60th anniversary of Walt Disney Records or the 110th birthday of Mickey Mouse voice Jimmy Macdonald.

But today, May 28, 2023, is the 82nd anniversary of one of the most important events in the Walt Disney Company’s history and you will not hear a peep out of the company. Unlike most anniversaries, the outcome of this event still impacts the daily lives of thousands of animators and ensures the existence and continued growth of the entire American animation industry.

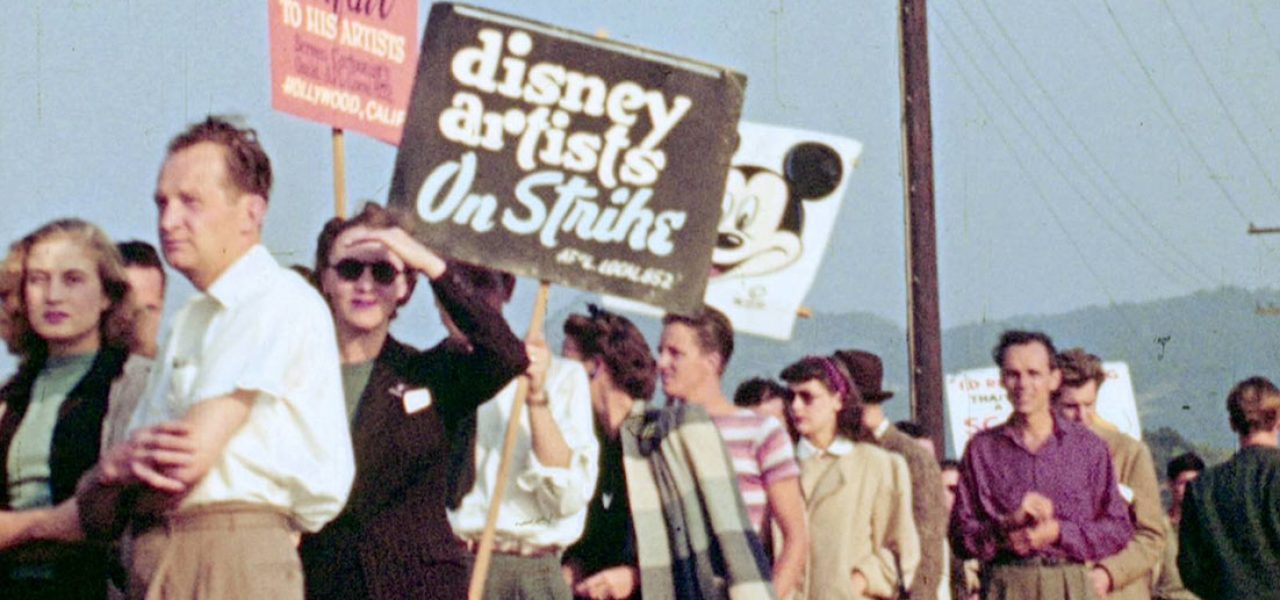

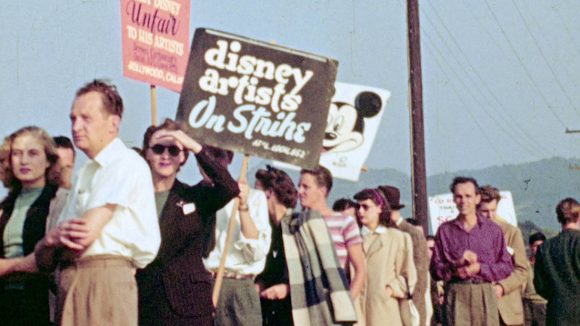

The event: on May 28, 1941, 334 employees of the Disney animation studio walked out on strike (303 employees remained on the inside). The events that led up to the strike are too numerous to recount here, but suffice to say, tensions had been building at the studio since the runaway success of the studio’s first film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937, and employees of the studio had a litany of grievances from low wages and salary cuts to arbitrary layoffs, arcane bonus distribution systems, and oppressively long hours (including mandatory work on Saturdays).

The strikers vowed to stay on the picket lines until Walt Disney recognized their union. With neither side willing to give in, the event lasted into the fall, turning uglier and lasting longer than either side had ever imagined. In the end, the workers won, and neither the Disney company nor the animation industry would ever be the same again.

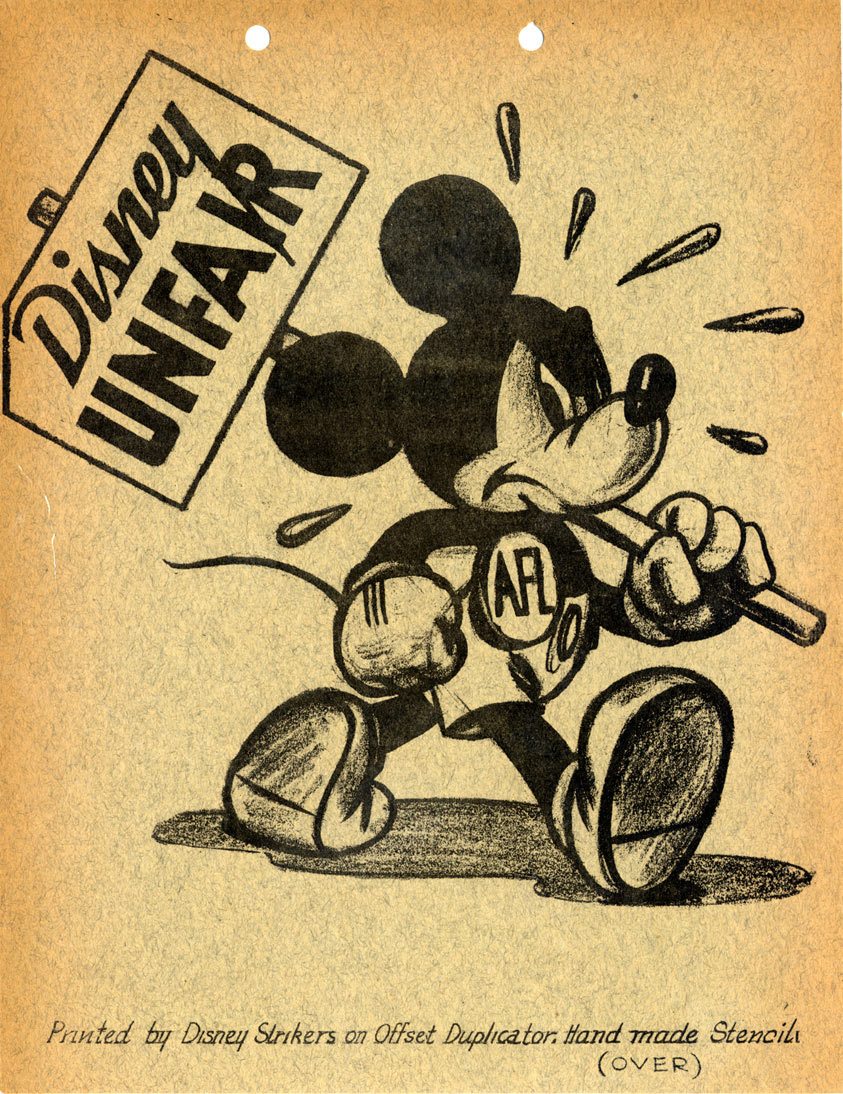

“It was the Civil War of Animation,” said Tom Sito, former president of The Animation Guild Local 839, and a Disney animator/story artist in the 1980s and ’90s. “The strike paved the way for Hollywood animators to earn pensions, medical insurance and the highest standard of living in the animation world.” (Sito has written about the strike extensively in his book, Drawing the Line: The Untold Story of the Animation Unions from Bosko to Bart Simpson.)

The Disney strike was not the first animation strike. In 1937, East Coast artists at Fleischer Studios had picketed. (In fact, much of the country had been striking since the passage of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, a foundational statute of workers’ rights that gave employees the right to form trade unions and negotiate collectively.) But the Disney strike was different because then, as now, Disney was the most prestigious name in American animation.

If Disney was held to a higher standard, other industry players would be compelled to follow its lead. And so, on May 29, 1941, the journey to improving the working conditions of animation craftspeople took one of its most significant steps forward.

The union is not a panacea for all of the animation industry’s labor ills. It is also not the strongest union in Hollywood, not by a long shot. But to this day, it remains the best option for artists who want to earn pensions and medical insurance, and ensure that they are treated with basic dignity and fairness by their employer. Union shops in Los Angeles understand that they can’t take advantage of their employees, which is why some animation studios, like Titmouse, try to skirt the system by launching satellite studios in other parts of the United States where they can pay employees less than a living wage.

While a union seems like a no-brainer for keeping employees happy and content, they are still resisted by people in positions of power, whether that person be the co-creator of Rick and Morty or Ed Catmull, the current president of Walt Disney Animation Studios. Catmull is staunchly anti-union, and has fought tooth-and-nail to keep the company he co-founded, Pixar, a union-free shop. As a result, even though Pixar is now owned by Disney, and even though Pixar has been the most financially successful animation studio in America for the last twenty years, the average starting wage for animators at the studio remains below unionized feature animation workers.

It also shouldn’t be a surprise that Catmull has emerged as the mastermind behind a wage-fixing scheme that has rocked the feature animation world over the past year, with evidence emerging that Catmull has worked for decades to prevent the industry’s employees from advancing their careers or being paid what they were truly worth.

Seventy-five years after the start of the Disney strike, as we honor the sacrifices of the brave women and men who improved workplace conditions for themselves and tens of thousands of artists who followed them, we must recognize that there is still plenty of work to do and that improving the industry’s welfare is a shared responsibility passed from one generation to the next. As for the Disney Company itself, let’s just say the strike worked out pretty well for them, too: the company today is worth $163 billion, making it the most valuable entertainment conglomerate currently in the world.

Below: a gallery of picket-line photos and ephemera from the 1941 strike, many of which come from the collections of Bob Cowan, Michael Barrier, and Jake Friedman:

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the date that the strike started. It was May 28, 1941, not May 29.

.png)