15 Reasons Why Frank Tashlin Was Awesome

Today marks the centennial of Frank Tashlin (February 19, 1913 – May 5, 1972), one of the most important figures in the history of American animation.

Frank who?

If Tashlin is recognized at all by the general public, it is for being the Looney Tunes animation director who ended up making kooky, subversive live-action comedies starring the likes of Jerry Lewis and Jayne Mansfield.

He was so much more than that though—a restless and ambitious creative powerhouse who didn’t play by anyone’s rules and whose filmic innovations were often decades ahead of their time.

Tashlin’s reputation has been bashed routinely by film critics, both while he was alive (“Tashlin has become sympathetically obsolete without ever becoming fashionable”—Andrew Sarris) and after he died in 1972 (“Tashlin remained the safe, cold-blooded side of bad taste, never came to terms with the full-length form or the live-action image, but never sensed the pungent onslaught in cartoon that, say, Gillray or Ralph Bakshi have achieved.”—David Thomson). Even online, it sometimes feels that he gets no respect; the editors of the Looney Tunes Wiki can’t identify Tashlin well enough to put up an actual photo of him on his biographical entry.

Still, Tashlin’s work persists and the impact of his unconventional, exaggerated style of cinema continues to reverberate throughout contemporary film. To celebrate Tashlin’s 100th birthday, Cartoon Brew presents 15 fun facts about Frank Tashlin. To learn more about him, visit Tish Tash: A Blog Tribute to Frank Tashlin and pick up a copy of Ethan de Seife’s recent book Tashlinesque: The Hollywood Comedies of Frank Tashlin.

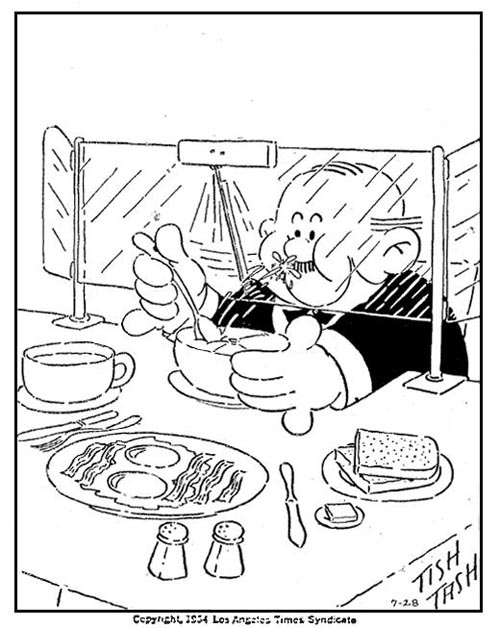

1. He named his buffoonish newspaper comic character Van Boring as a dig toward his former boss, Amadee J. Van Beuren, who ran Van Beuren Studios.

More of the Van Boring strips are posted on Facebook.

More of the Van Boring strips are posted on Facebook.

2. He knew that Porky Pig was a chump and loved to make fun of him.

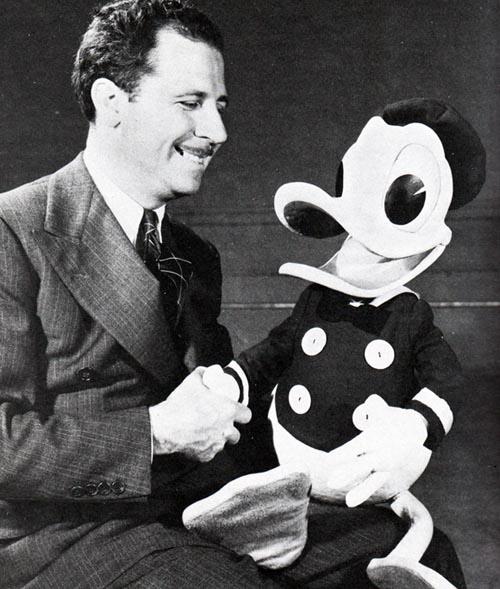

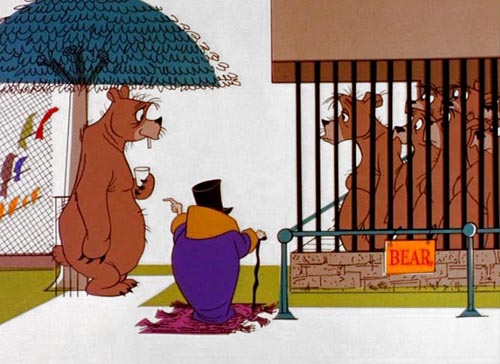

3. He once claimed that when he worked at Disney, one of his favorite things to do was throw Clarence Nash, the voice of Donald Duck, out of the window.

Tashlin told historian Michael Barrier in 1971:

They didn’t know what to do with a fellow by the name of “Ducky” Nash—Clarence Nash, he was the voice of Donald Duck—because when they weren’t recording Donald Duck, what do you do with the fellow who’s the voice of Donald Duck? Ducky had an office in this building, a little tiny office where he would come over and go to sleep. These were hillside places, and the ground beneath his window was maybe twelve feet. Roy Williams, this big fellow, and I, when Ducky was asleep—and he slept just like a duck, he made funny sounds—in this big wicker chair, we would take this chair, with him in it, and we would hold it out the window, and drop him. This chair would hit, and because it was wicker, it sort of had a recoil, you know, the legs went out like this. He’d start quacking away down there, and he’d come up, dragging this chair with him. This happened many times, and it was a high point of humor—you know, you want to talk about low humor, that’s what we thought was funny.

4. He directed the most elegant, cinematically modern black-&-white cartoons in the history of animation.

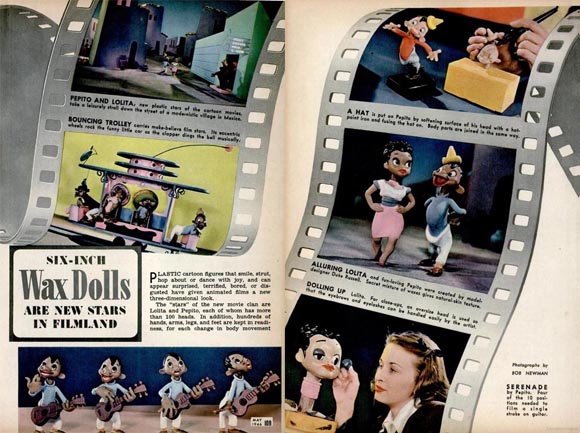

5. His eclectic career is full of detours into different areas of film, like when he made the stop motion films The Lady Said No (1946) and The Way of Peace (1947).

Tashlin scholar Ethan de Seife has written extensively about The Lady Said No.

6. He played an important role in kickstarting the ‘cartoon modern’ era.

When Tashlin became the head of Columbia’s Screen Gem studios in 1941, he transformed it into a haven for artists who wanted to create modern-looking animation. Zachary Schwartz, who became a founder of United Productions of America, said of Tashlin, “He was an inspirational man to work for.” Another animation modernist, John Hubley, said of his experience, “Under Tashlin, we tried some very experimental things; none of them quite got off the ground, but there was a lot of ground broken. We were doing crazy things that were anti the classic Disney approach.” The visual experimentation continued for a couple years after Tashlin’s departure from Columbia, such as in this 1943 short Professor Small and Mr. Tall:

7. He created the Fox and Crow.

The Fox and the Grapes, the first cartoon that Tashlin directed with these characters, featured a novel blackout-gag structure that served as a model for many later cartoons, including Chuck Jones’ Coyote and Roadrunner series.

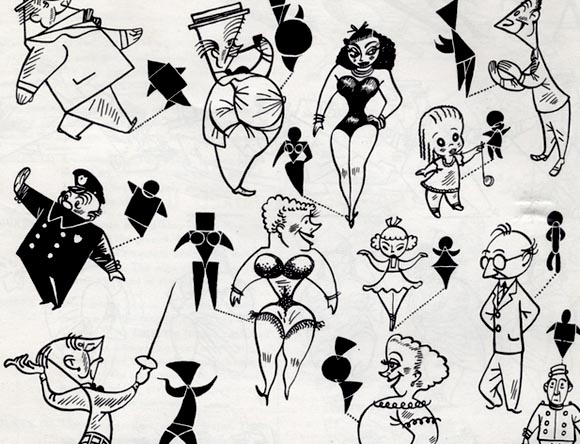

8. He invented his own system of cartooning called SCOT-ART.

Tashlin’s how-to cartoon book proclaimed that anybody could create original cartoons if they could draw S(quares), C(ircles), O(vals) and T(riangles). You can find the entire book HERE.

Tashlin’s how-to cartoon book proclaimed that anybody could create original cartoons if they could draw S(quares), C(ircles), O(vals) and T(riangles). You can find the entire book HERE.

9. Jean-Luc Godard loves him:

Says Godard:

Says Godard:

According to Georges Sadoul, Frank Tashlin is a second-rank director because he has never done a remake of You Can’t Take It With You or The Awful Truth. According to me, my colleague errs in mistaking a closed door for an open one. In fifteen years’ time, people will realize that The Girl Can’t Help It served then—today, that is—as a fountain of youth from which the cinema now—in the future, that is—has drawn fresh inspiration….Tashlin indulges a riot of poetic fancies where charm and comic invention alternate in a constant felicity of expression….Frank Tashlin has not renovated the Hollywood comedy. He has done better. There is not a difference in degree between Hollywood or Bust and It Happened One Night, between The Girl Can’t Help It and Design For Living, but a difference in kind. Tashlin, in other words, has not renewed but created. And henceforth, when you talk about a comedy, don’t say ‘It’s Chaplinesque’; say, loud and clear, ‘It’s Tashlinesque’.

10. John Waters loves him:

11. He allowed Chuck Jones to adapt his illustrated book The Bear That Wasn’t into an animated short, and when Jones ruined the film, he never spoke to him again.

12. He married Mary Costa, who was the voice of Princess Aurora in Disney’s Sleeping Beauty.

13. He created an amazing graphic novel called The World That Isn’t.

This bleak yet perceptive commentary on modern American life is as relevant today as when it was first published over sixty years ago. Tashlin uses the cartoon medium to expose the follies of humankind, including religious intolerance, environmental destruction, political corruption, tabloid trash, celebrity worship, and nationalism. In his cautionary tale, mankind finds peace only after destroying himself through nuclear apocalypse and starting over again.

14. He was a leg man.

This one hardly needs explanation.

.png)