Pablo Berger Created A Pop-Up Studio In Downtown Madrid To Make His Animated Debut ‘Robot Dreams’

The Spanish animated feature Robot Dreams received an overwhelmingly positive reaction when it debuted at Cannes earlier this year, where it was quickly snapped up for U.S. distribution by indie powerhouse Neon, which will release the films in U.S. theaters in 2024.

Robot Dreams is directed by Spanish auteur Pablo Berger and produced by Arcadia Motion Pictures. The only other animated film Arcadia has ever produced was 2016’s Ozzy – Bad Dogs, and Berger has never worked on an animated production.

It’s exceptional, then, that the two teamed to make one of the year’s most touching animated features that, if distributed well, will live long in the hearts of audiences. Even more so considering the film’s budget was an extremely modest 5.5 million euros ($6 million).

We recently sat down with Berger to talk about making his animation debut, setting up a bespoke animation studio in central Madrid, and the superpower he believes all directors possess.

Cartoon Brew: You’ve had an outstanding career making live-action films. Blancanieves is a modern Spanish classic and received 10 Spanish Academy Goya Awards and Torremolinos 73 is iconic. That said, this is the first time you’ve worked in animation. What inspired you to want to take that leap?

Pablo Berger: The main reason is right here in my hands; it’s Sara Varon’s graphic novel. I collect graphic novels and illustrated books that have no words, and I read Robot Dreams for the first time in about 2010. I was captured by it. It had beautiful graphics; it was fun, surreal, and emotional. So, after I made my films Blancanieves and Abracadabra, I was thinking about what to do next and looking at my bookshelf. I pulled out Robot Dreams and started paging through the book, and I felt the same thing as the first time I read it, but it was more intense this time.

Did you know immediately that you wanted to adapt the book as an animated film?

I don’t want to spoil anything, but when I got to the end of the book, which is much shorter than in the film, it brought tears to my eyes because I was seeing the film in my mind. I think if directors have one superpower, it’s that we can close our eyes and see a finished film. So, when I saw that in my mind, I realized something new had happened to me. I never, not in a million years, thought I would make an animated film. I love animation, and I’m a huge cinephile, but I had never worked in animation before. But the story was so powerful, and the way it talked about themes of friendship, the fragility of relationships, and how we overcome loss by using our memories, I knew I had to make this film.

So, where did you start? Did you have connections in the animation industry?

On all of my films, I work closely with my crews. I always recruit the best supervisors, executive producers, editors, and musicians. When I started thinking about this project, I reached out to the best producer I knew in the animation business, Ivan Miñambres from Uniko. Like me, he’s from Bilbao. He’s worked on incredible films like Unicorn Wars and Birdboy and many award-winning shorts. We were both at Madrid Animation Day in 2018, and I pulled him aside and told him I was thinking about making an animated film. I hadn’t even told my own producers yet at that point. I started telling him all my ideas, and he said, “Look. Before you do anything else, you have to get the best animation director you can find. They’ll be your right hand and your left hand through production.” So that’s what I did; I went and recruited the wonderful art director Jose Luis Ágreda, who previously did Buñuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles, and he was with me from the very beginning. And later, I hired the incredible animation director Benoît Feroumont, who had done The Triplets of Belleville and The Secret of Kells. They both became the leaders of my “dream team

Were your producers surprised when you finally told them about your plan?

I’ve worked with the same producer, Arcadia, for years, so they know me well and weren’t surprised when I told them about my idea. If there is one thing they would all say about me, it’s that they never know what I’ll do next, so they’re always ready for something unexpected.

When did you start writing the film? And did that process differ from how you work on your live-action films?

On all my live-action films, I prepare extremely detailed storyboards for the entire film, not just the action or dramatic scenes. For me, the final draft of a script is the storyboard. On Blancanieves and Abracadabra, I spent almost a year working on the storyboards. So, without being conscious of it, I was already writing a bit like an animation filmmaker. I think that really helped prepare me to make a film like Robot Dreams. I found the transition so natural. Of course, I was frightened at first, but I think it should be frightening to start any new project, live-action or animation.

Because I did Blancanieves, I know what it takes to make a film without dialogue. The main requirement is that the film has to be full of small actions, and it needs thousands and thousands of shots. You really depend on action-reaction. I think Robot Dreams probably has two or three times more shots than any other animated film this year.

Did you storyboard all of Robot Dreams?

No, it was a team effort. I had a storyboard artist lined up in 2018, but at the last minute, he had another obligation and couldn’t join me. So, I took the unusual decision and asked my art director to do the storyboard with me. He’d never done one, but I insisted he was the right person. To help, we hired Maca Gil, an incredible storyboard artist who has worked for Cartoon Saloon. Together, we sat in a circle here in my office, the art director and I would do the thumbnails and then Maca, using them as refence, would draw the storyboard with Storyboard Pro. We also had my music editor, Yuko Harami, with us, who is a major part of all my films and my closest collaborator. We were all in the same space for the entire development of the film, working together every day. It was one of the most satisfying and creative experiences of my life. Later, my editor, Fernando Franco, would revise the storyboard and propose changes to improve it.

Can you talk about the film’s production? Who animated Robot Dreams?

We were able to finance the film very quickly, so we immediately started looking for a studio. Around that time, my art director spoke with Nuria González Blanco from Cartoon Saloon, and she asked what he was working on. When she heard about our film, she said we had to come to Kilkenny and talk to the Cartoon Saloon team. So, we went to Ireland, and they loved the idea and said they wanted to make the film with us. For a while, Cartoon Saloon was going to be the studio for this film. Then Covid happened, and they had to back out. That meant we had a fully-financed animated project but no animators. We had to make a big decision, so I said, “Let’s make a studio here.” And that’s what we did. We set up a pop-up studio near Gran Via in Madrid and another smaller studio in Pamplona. Then, we brought in animators from all over Europe to work on the film. Although this was during the pandemic, it was vital for us that we had a physical studio where everyone could work. It wasn’t ideal; we all spent a year wearing masks, but it was worth it in the end.

That’s incredible. Can you tell me more about creating a single-use animation studio?

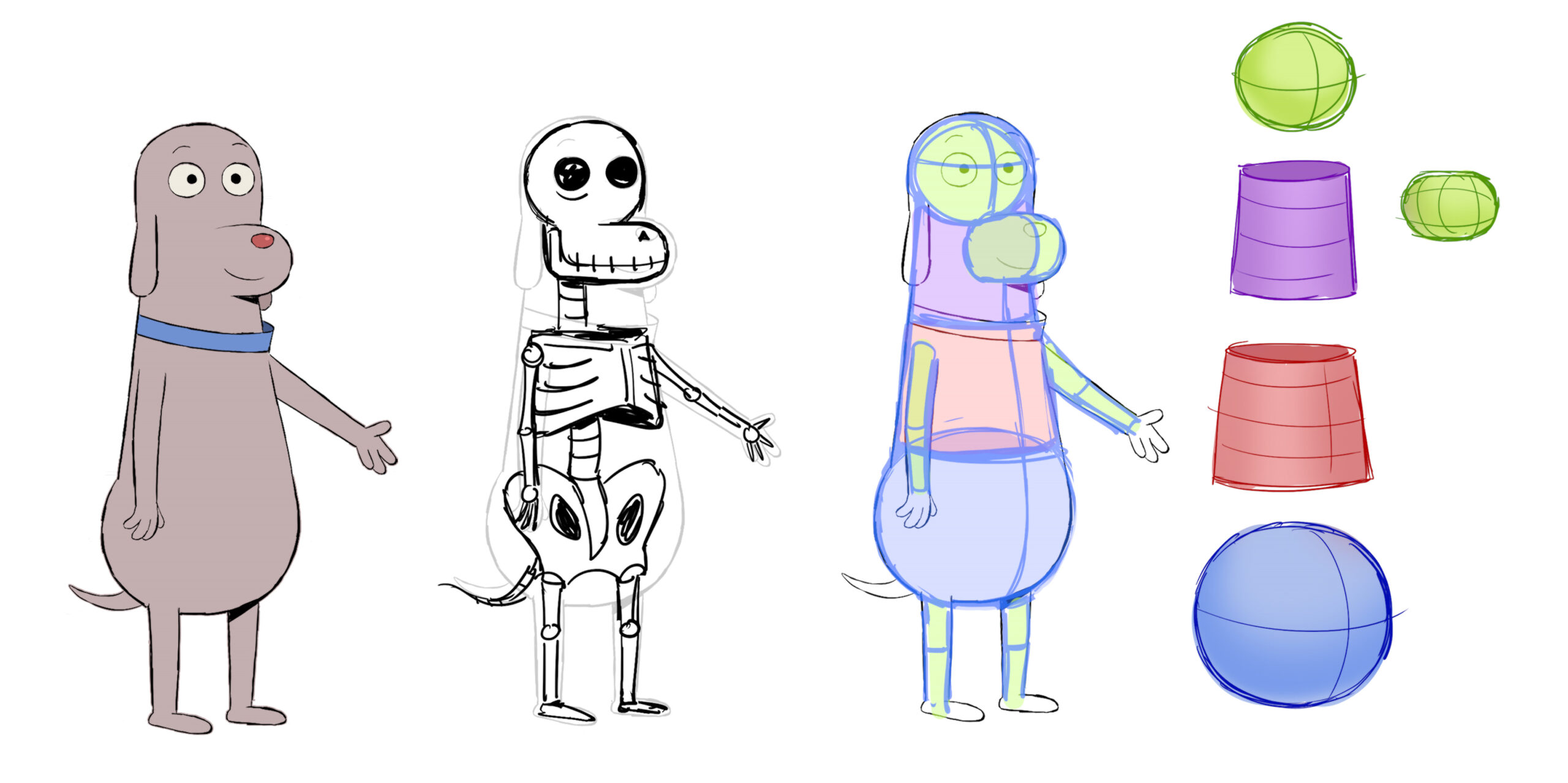

We had to buy all the machines used for production. We used Harmony and Storyboard Pro and had to create a pipeline, which was new to me because I had no idea what an animation pipeline was until I started making this film. All of a sudden, we had all these workflows and boxes [to check off], and I was trying to figure out what it all meant. That’s one area where I think it was maybe helpful that Cartoon Saloon had to back out because I would have had to adapt to their pipeline if they’d done the animation. Because we set up our own studio, it was more of a negotiation between the animation team and me. It took time, maybe two or three months of back-and-forth, but it all became pretty smooth once we figured out our pipeline. Of course, I would have loved to work with Cartoon Saloon, but I think, in the end, I could do things more my way.

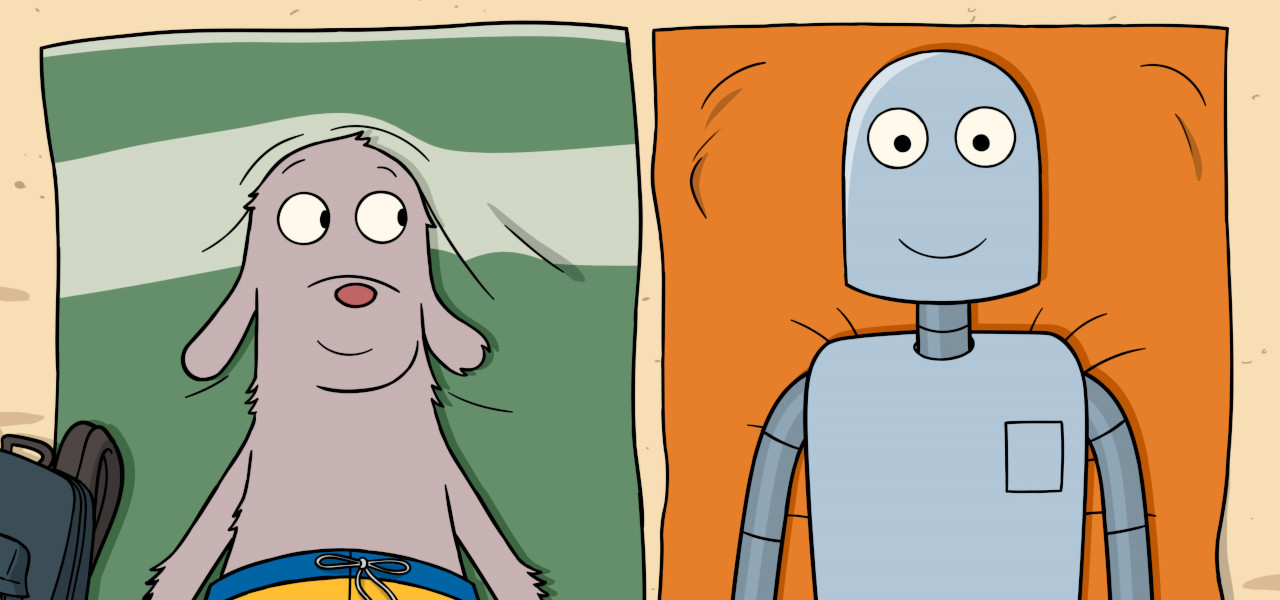

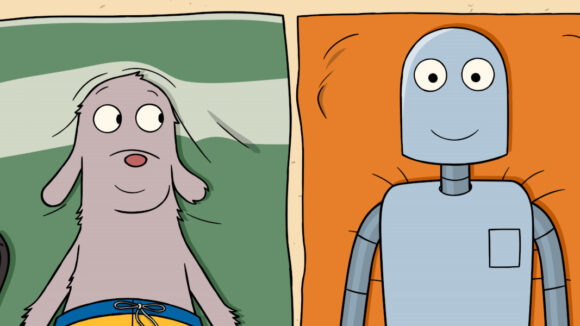

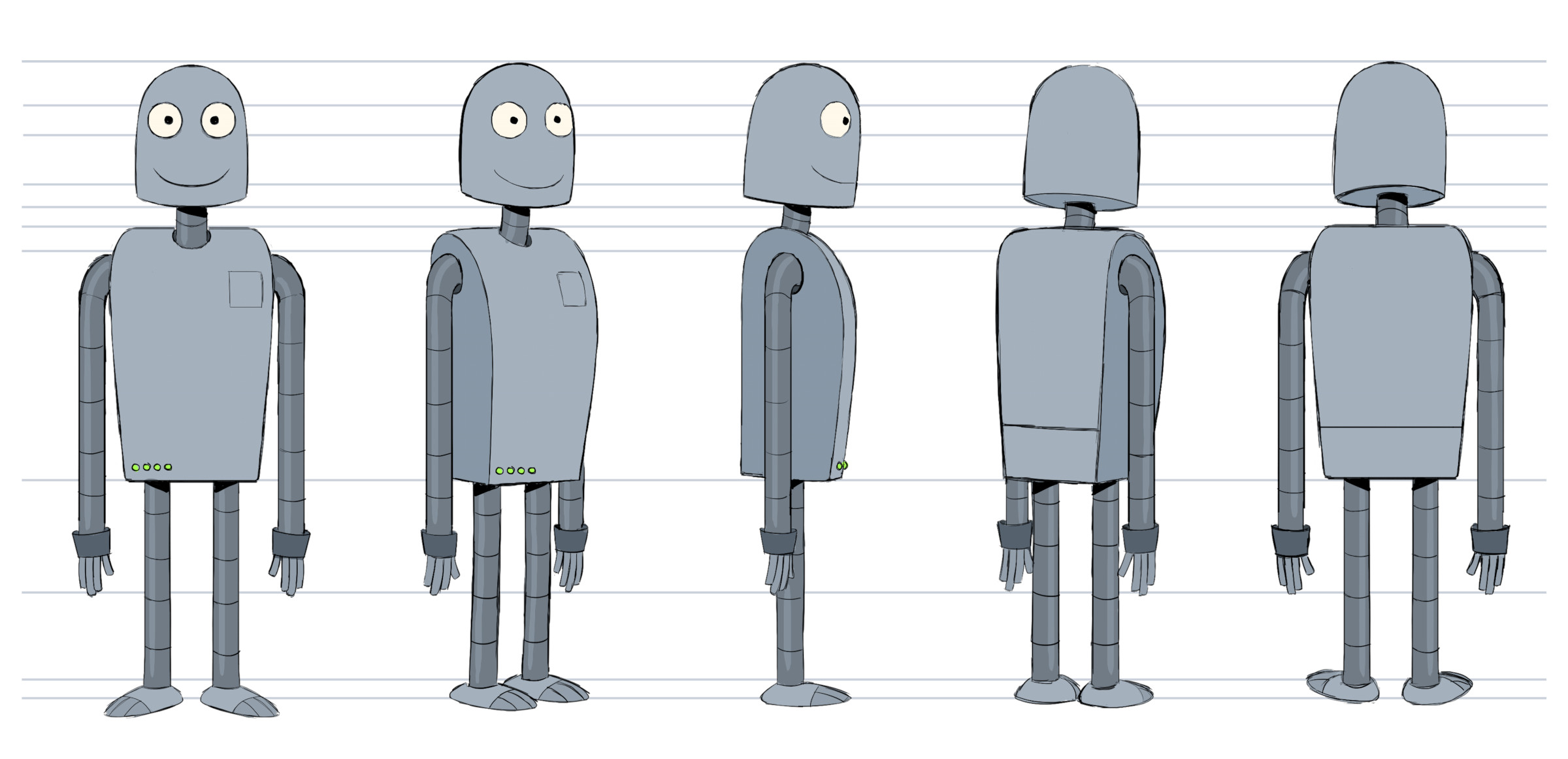

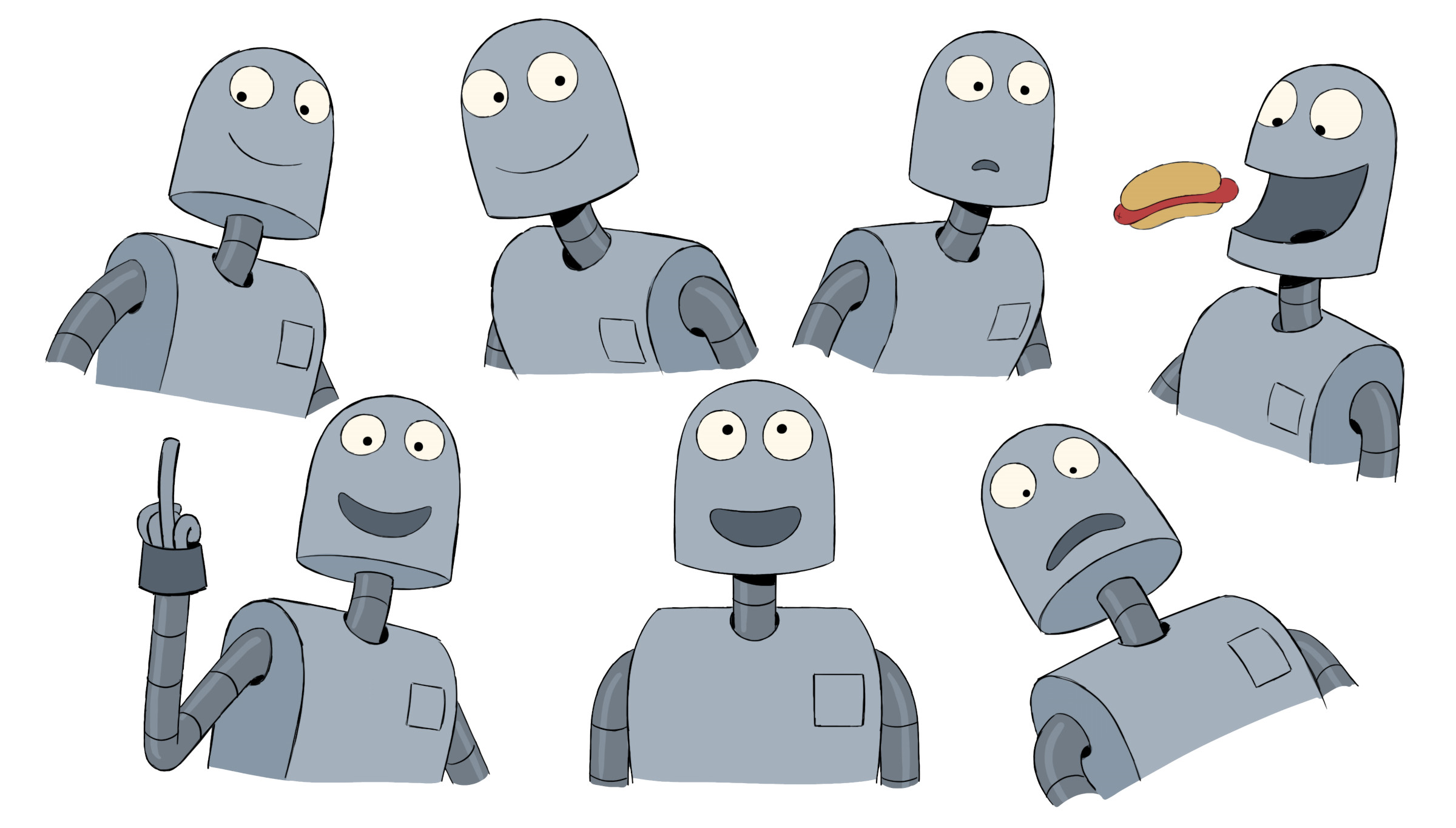

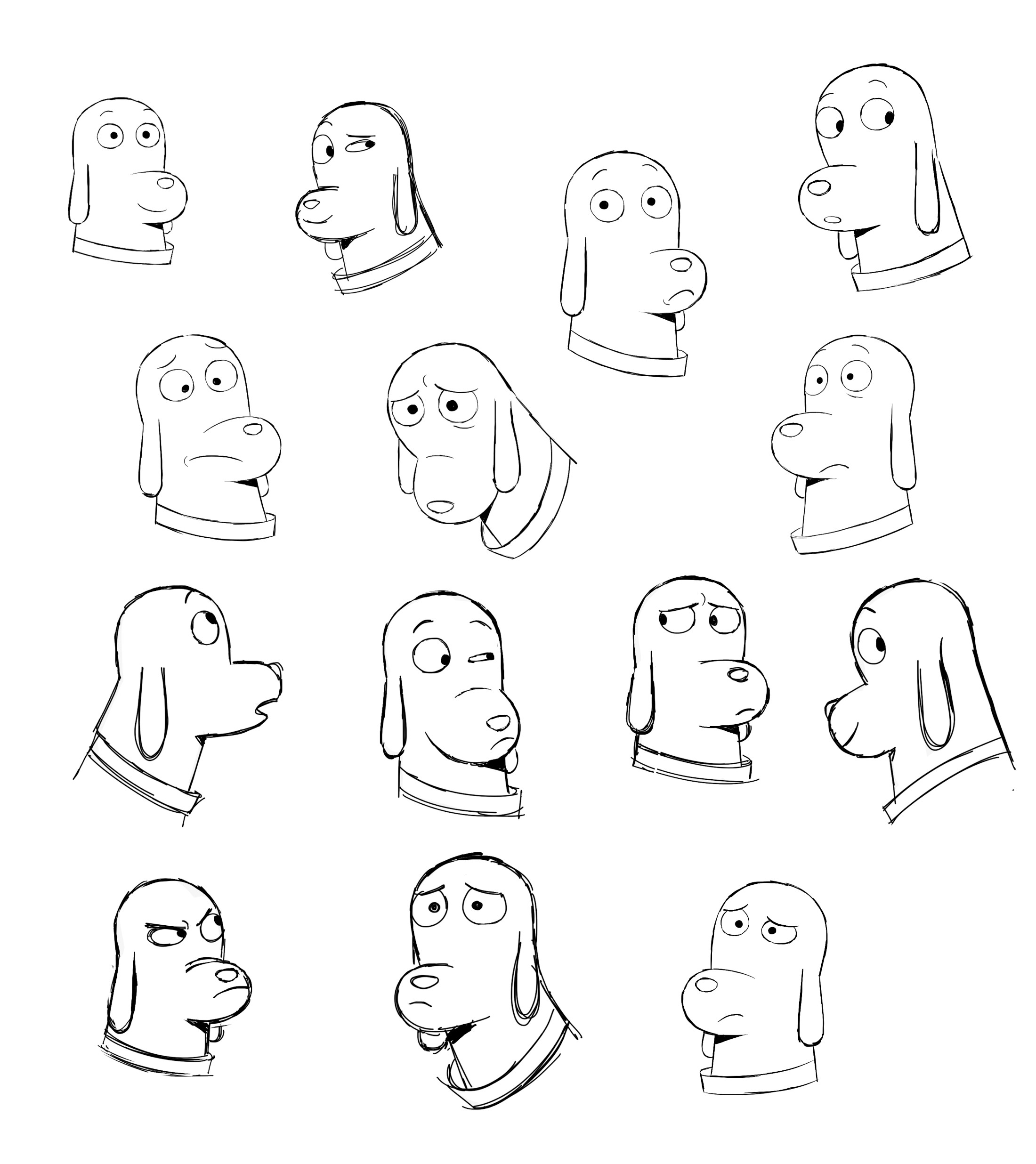

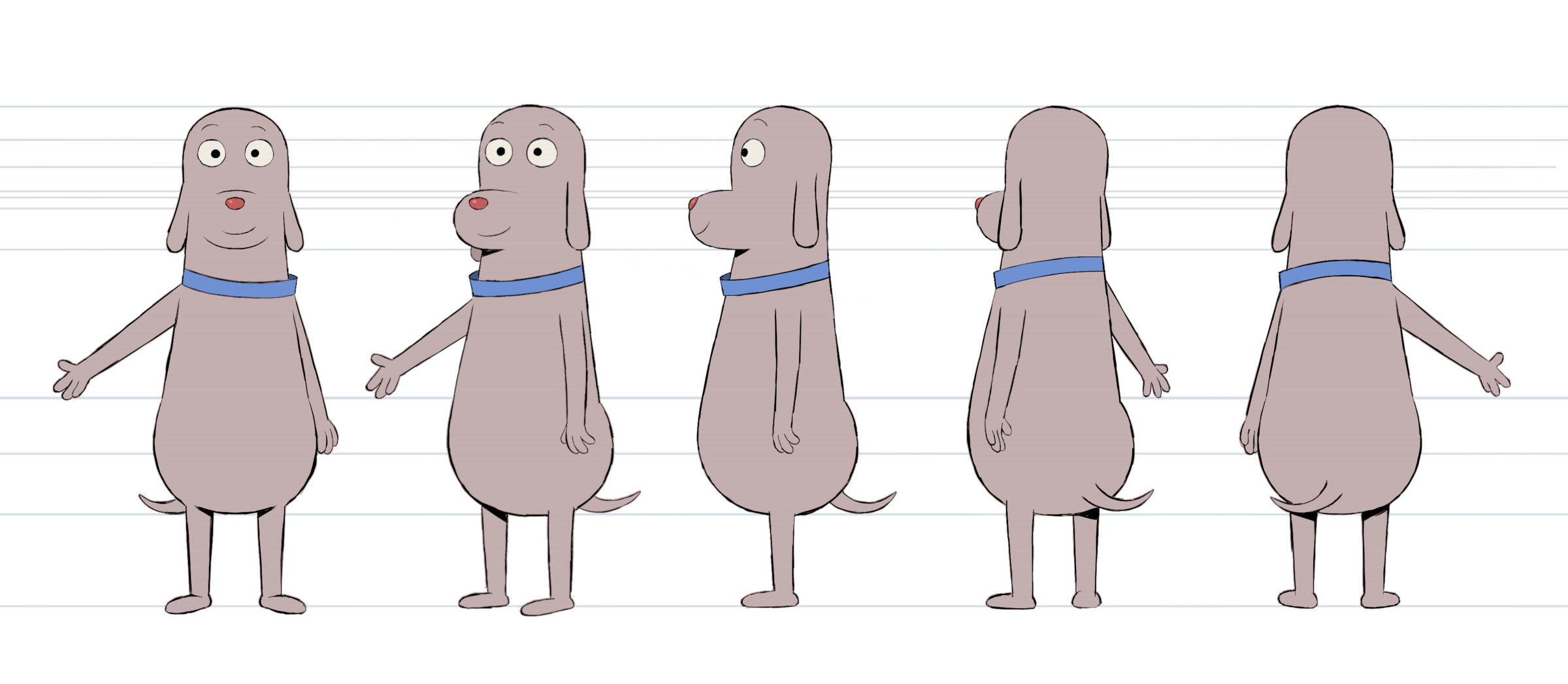

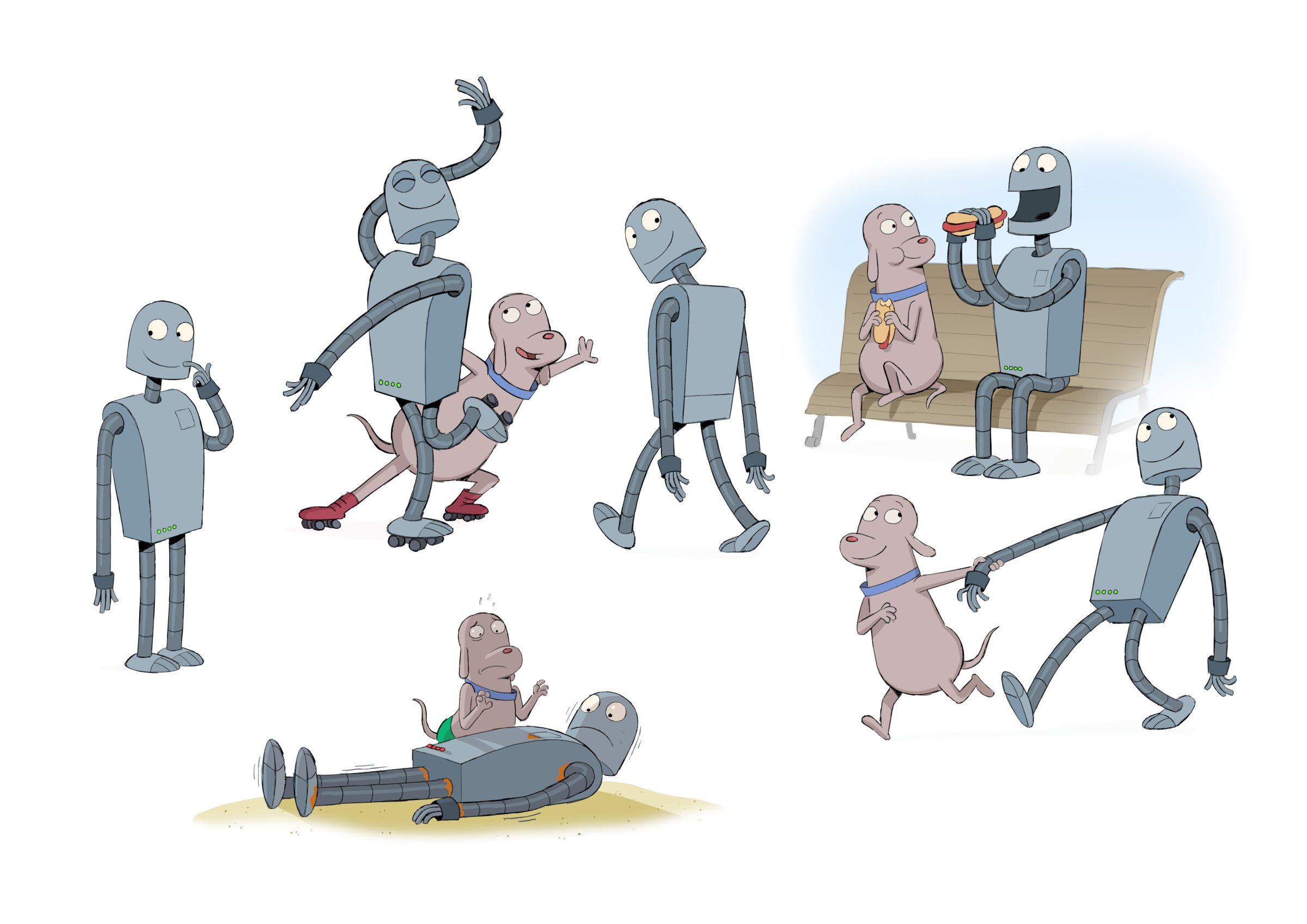

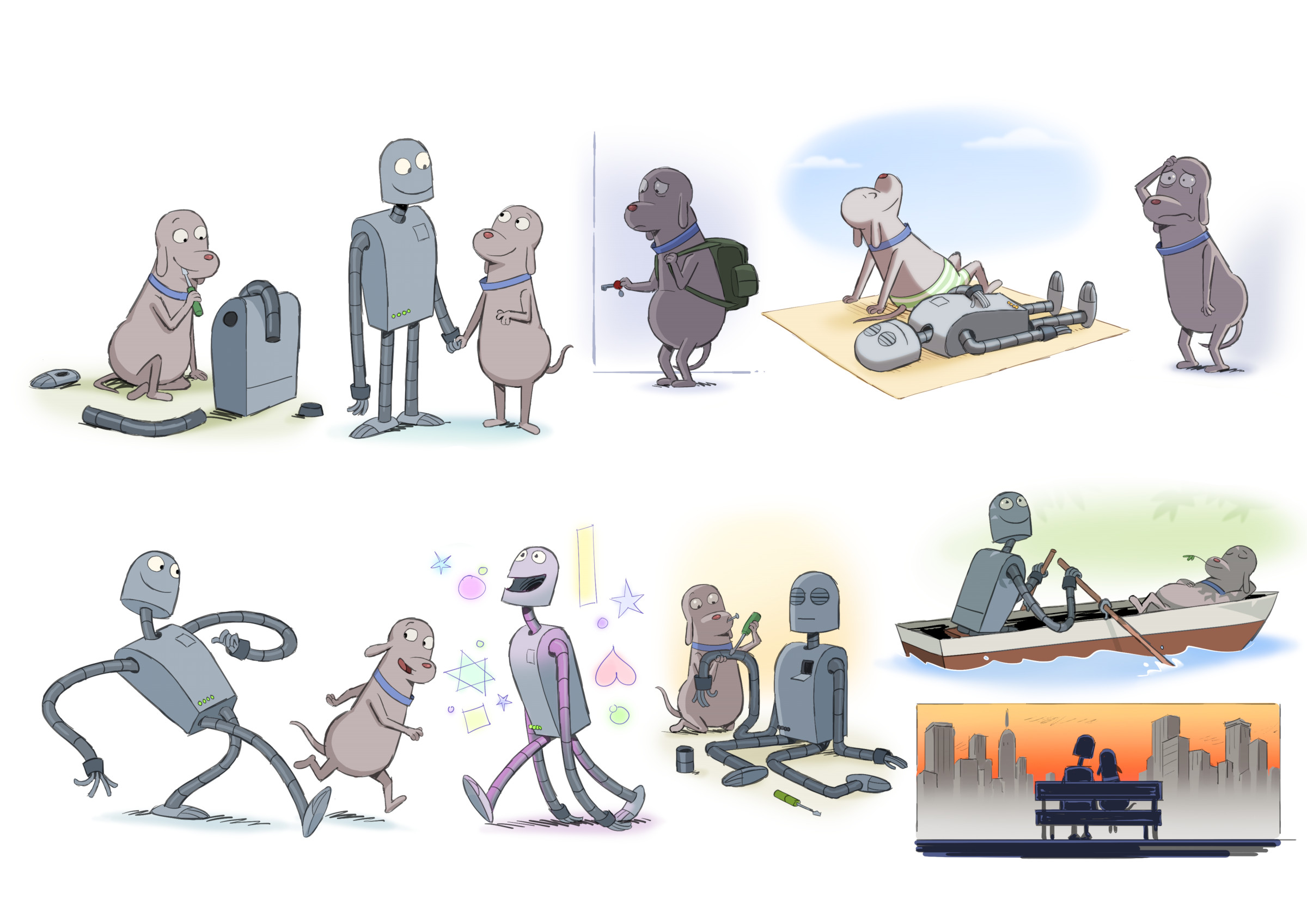

Obviously the look of the film is based on the book, but can you talk a bit about the visual development process? How did you decide what the characters and sets would look like? Because they’re much more detailed than the book.

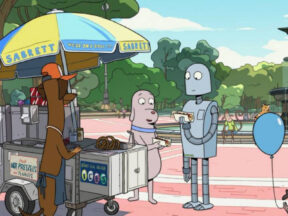

When I was preparing, I noticed that in a lot of animated films, most of the time, the characters in the background aren’t very sophisticated. They’re often still; they don’t move. They’re just scenery. I am used to working in live action, and as a live-action director, the protagonists, the supporting actors, and the people in the background and equally important. So, all the extras, all the New Yorkers that appear in the film, have a reason for being there. They all have a story and their own objectives. They also have their own unique designs. If you watch this film over and over, you should notice something new in the background every time.

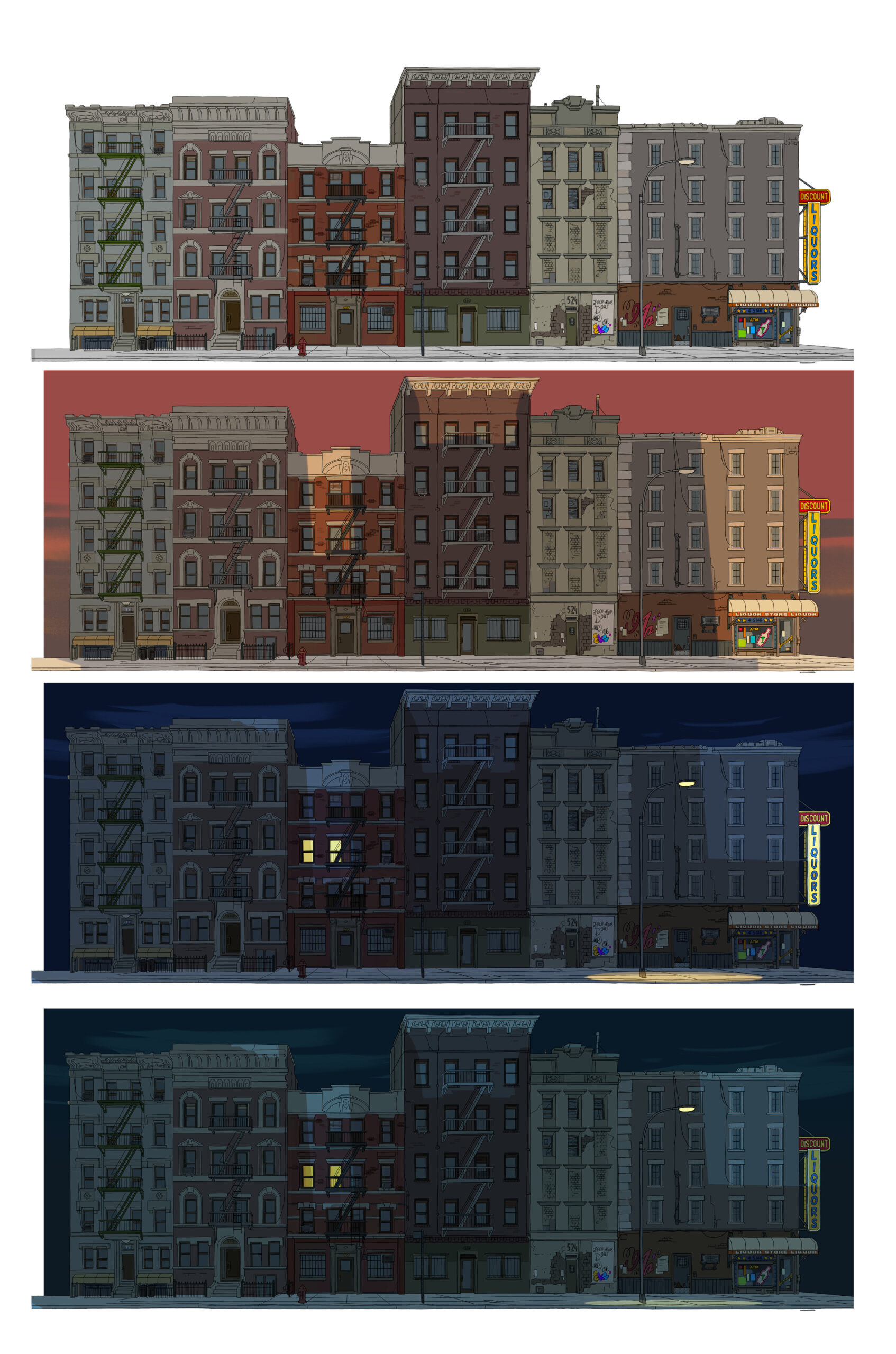

Visually, one of biggest changes from the book is that we also made New York a protagonist. So, the art director and his team had the challenge of creating a realistic 1980s New York. The character design of Robot and Dog evolved from the graphic novel to the film, but probably the biggest changes came when designing the extras, the new Yorkers.

There is a common misconception that Robot Dreams is a kids’ movie. It’s appropriate for kids, but the themes of loss and memory are far more relatable for adults who have experienced these types of relationships. What audience were you thinking about when you made this film?

For us, it was never a kids’ movie. Sara’s book wasn’t meant for kids either. Of course, it’s got kid-friendly designs and colors, and I think kids will enjoy the film, but we never considered adding anything or leaving anything out for kids. For me, the most important audience for any of my films is me. That may sound selfish or egocentric, but I make all of my films with myself as the main target, and after me is the team I’m working with. It’s been my experience that making films that way has the greatest impact. I made my first short, Mama, in the 1980s, and it was very punk. I didn’t know how to make films then, but I did something I knew I would enjoy. It ended up winning many awards and played at the biggest festivals, including Clermont Ferrand. I learned then that I had to make very personal films and that the audience would come later.

.png)