‘Mouse in Transition’: “Call Us Mike and Frank” (Chapter 14)

New chapters of Mouse in Transition are published weekly on Cartoon Brew. It is the story of Disney Feature Animation—from the Nine Old Men to the coming of Jeffrey Katzenberg. Ten lost years of Walt Disney Production’s animation studio, through the eyes of a green animation writer. Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg. Since 1989, Hulett has served as the business representative of the Animation Guild, Local 839 IATSE, a labor organization which represents Los Angeles-based animation artists, writers and technicians.

Read Chapter 1: Disney’s Newest Hire

Read Chapter 2: Larry Clemmons

Read Chapter 3: The Disney Animation Story Crew

Read Chapter 4: And Then There Was…Ken!

Read Chapter 5: The Marathon Meetings of Woolie Reitherman

Read Chapter 6: Detour into Disney History

Read Chapter 7: When Everyone Left Disney

Read Chapter 8: Mickey Rooney, Pearl Bailey and Kurt Russell

Read Chapter 9: The CalArts Brigade Arrives

Read Chapter 10: Cauldron of Confusion

Read Chapter 11: Rodent Detectives and Studio Strikes

Read Chapter 12: Disney Dead-Ends and Lucrative Mexican Caterpillars

Read Chapter 13: Basil Kicks Into High Gear

In the Seventies and Eighties, the Disney studio’s physical plant hadn’t changed much from the days of its founder: same art deco buildings from the 1940s; same stucco cracker-boxes dragged over from the old Hyperion Studios. Same sound stages.

The only new addition was an ugly concrete monstrosity called “The Roy O. Disney Building” inside the wall along Buena Vista Street. It housed publicity and a few other departments. A smart-ass traffic boy told me it was ugly because the structure was the end-result of the lowest bid from the outside architect and contractor who put it up. Multiple stories of gray concrete, the building looked like a government bunker from East Berlin.

Yet even though the company seemed like a quiet backwater, there were significant changes going on: Tokyo Disneyland was in the works. EPCOT at Disney World was on the drawing boards. And after years of mulling the idea over, the company launched a cable network called The Disney Channel. In its early days, various studio employees were enlisted to create low-cost programming: video documentaries, bare-bones kid shows, and recycled network programs. The low quality led many of us in the animation department to predict an early death for the company’s television brainchild. We turned out to be way wrong.

Walt Disney Productions was becoming less a movie studio and more a real estate holding company. The big profit centers were the amusement parks, yet even with Disneyland and Disney World, management was averse to taking large swings at distant fences. EPCOT might have been greenlit for construction in Florida, but it was more a permanent World’s Fair than Walt’s Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow. A working metropolis in the middle of a big resort was, apparently, not something the Walt Disney-less Disney was prepared to do. Another amusement park? That was a different story.

Still in all, the Florida property was where the action seemed to be. Ward Kimball came out of retirement to work on General Motors’s EPCOT Transportation Pavilion, and Disney management arranged for the animation staff to journey to WED (Disney’s design center for the parks) to get a tour of EPCOT’s rides and exhibits.

For most of one workday we wandered among three-dimensional models and ride mockups, gaped at the big-screen presentations of what was to come. Then we got a pep-talk/sermon on the glories of the new park from Marty Sklar, the man in charge of the operation. He described EPCOT as big, fresh, and original. I asked about Walt’s original concept of a self-contained city. He said the original concept had been impractical.

At a catered lunch, the WED creators and engineers were introduced to animators and storyboard artists. I found myself sitting next to a jovial long-haired man named Rolly Crump, who told me he had worked at WED since Walt had come to his animation office one morning in 1960, spotted the intricate mobiles Rolly had hanging from the ceiling, and decided that Mr. Crump would be better used creating amusement park rides than drawing black spots on cartoon dalmatians.

Most of the live-action movies that Walt Disney Productions was making in the late seventies and early eighties were pale retreads of the films produced in Walt’s last decade: The Apple Dumpling Gang Rides Again, The Cat From Outer Space, Herbie Goes Bananas. The young newbies on the animation staff yearned for something better. When an independent film called Time Bandits was screened in the big studio theater because its Brit producers were looking for a distributor, a bunch of us campaigned for the studio to pick it up. The movie was not only zesty, original, and funny, but had Sean Connery and half the Monty Python comedy troupe in it.

Sadly, the studio passed on the project, and Avco Embassy Pictures snatched the film up, making a sizable fortune. (A $42 million gross against a $5 million budget, amazing for the early-’80s.)

But the whole structure of the company was starting to change, if only by fits and starts. Tom Wilhite, a young hot-shot executive who ran the studio’s publicity department (and looked like actor Parker Stevenson’s twin brother) was promoted to head of studio production and started shaking things up.

Tom had lunch with the young animation staff and listened to their complaints. He took note of assistant animator Tim Burton’s ambitions and helped Tim direct live-action projects, which included fairy tales for the Disney Channel and a story about a dog that came back from the dead. He boosted John Lasseter’s and Glen Keane’s experimental computer work with a scene from Where the Wild Things Are.

But the hot project for Disney’s new production team was a movie called Tron, with many chases and action set-pieces happening inside a computer game program. A non-Disney animation director name Steve Lisberger pitched the project to Wilhite and company; a sale and fast-track development and production go-ahead quickly resulted.

The animation story department slogged forward with The Black Cauldron and Basil of Baker Street, but down on the animation building’s first floor, a story called The Brave Little Toaster was taking shape under the pencils of CalArts grads Joe Ranft, Brian McEntee, and John Lasseter. John wanted to produce it as a computer-generated, animated feature.

Studio head Wilhite sparked to the project, but the old guard in the feature animation department vigorously pushed back: “These guys are whipper snappers! And they didn’t go through channels! No cartoon about a home appliance around here! Just forget about it!”

So The Brave Little Toaster was strangled in its crib, and not long afterwards John Lasseter, who had been at the studio for five-plus years, was handed his walking papers, never to be heard from again. (Happily,Toaster found new life under the wing of the Disney Channel. Directed by CalArts alum Jerry Rees, art directed by Brian McEntee, and storyboarded in part by future Pixar legend Joe Ranft, the picture was produced on a microscopic budget in Taiwan.)

While this simmering warfare was happening below decks on the S.S. Mouse, up on the bridge new pressures and troubles were building. Tron, in work for over a year, (and much of the work happening inside the animation department), opened to so-so reviews and ended up overshadowed by Steven Spielberg’s E.T., which rolled out around the same time. Another feature—Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes—laid a damp fart at the box office. Shortly thereafter, Tom Wilhite was let go as studio production chief.

But a more ominous storm was brewing. Saul Steinberg, a New York-based corporate raider, started purchasing large amounts of Disney stock with the announced aim of taking the company over and breaking it into smaller pieces, each of those pieces sold at a profit.

Gloom descended on the animation department: “What’s going to happen to the cartoon FEATURES!?” Will they even keep making them?!” “Holy shit! Steinberg will sell off Disney World!”

The corporate maneuverings went on for months. Was the company going to disintegrate? Or would it hang together? Were Disney’s managers going to weather the assault? I fell into the habit of going across the third-floor hallway to the office of Ron Miller’s publicist Irwin Okun and asking him what the hell was going on. Irwin told me a family of Texas billionaires named Bass had stepped into the tug of war between Steinberg and Disney management and were helping the corporate side pull on the rope. “Everything will turn out fine,” Irwin said.

Relief. But that wasn’t the end of Disney’s civil war. Although Walt Disney Productions remained intact, Sal Steinberg marched away with millions of dollars, and Sid, Lee, Robert, and Ed Bass now owned ten percent of the company. And they were not enthralled with Disney management (meaning CEO Ron Miller.)

Rumors swirled that Ron was on thin ice, and would soon be gone. When Mr. Miller came downstairs to a story meeting on Basil, nobody had the gumption to ask him, “You staying or going?” (Nobody was suicidal.)

Next we heard that Roy Disney, Walt’s nephew and Ron’s long-time nemesis, was pulling strings to get Ron fired. (Ron and Roy had clashed for years. The most recent story around the lot was that when Roy had resigned from the studio’s board of directors, Ron beelined to the parking lot and tore Roy’s name-plate off of his covered parking space.)

The corporate in-fighting seemed to be settling down, but then a terse studio memo announced that Ron Miller had resigned as CEO. Nobody in the animation department was shattered by the news. Ron was liked, but beyond his occasional meetings with the story crews, he hadn’t been a forceful presence in anyone’s life. Among the animators and board artists, only Pete Young seemed truly dejected. “You know, it took me years to get Woolie Reitherman’s confidence,” Pete told me, slouched in his corner office. “He didn’t think I could do much of anything until I’d worked on a bunch of sequences for The Fox and the Hound. And right around the time he starts liking the ideas I have and the work I’m doing…BOOM!…Woolie’s not on the movie anymore.”

“Then there’s Ron,” Pete continued. “He didn’t know who I was, then I pitch him a movie proposal and he likes it, so I pitch more and he likes those, and everything is working out great. And now Ron is gone. It’s the story of my life.”

Everybody waited to find out who the new studio top-kick would be, but we didn’t wait long. Within days, another studio memo told us that Michael Eisner, (an exec from Paramount) and Frank Wells (a suit from Warner Bros.) were being installed by the Disney Board of Directors as the new Chief Executive and Chief Operating Officers of the company.

And there was yet another tale circulating: Ron had been asked to stay on as head of animation, but he had responded with a curt “No way.” We never had a chance to ask Ron if the rumor was true or not. He didn’t come around to say goodbye, but simply disappeared.

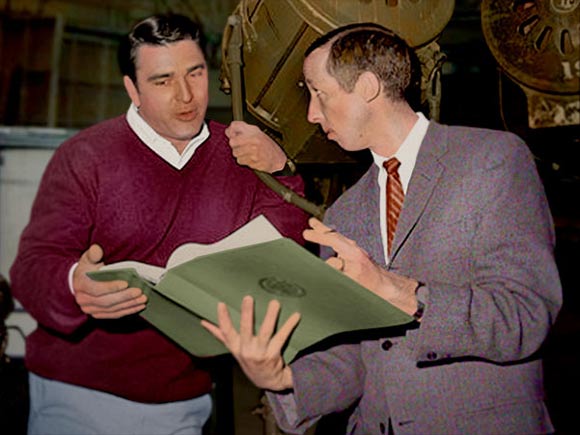

Studio employees got their first chance to see Disney’s new corporate chieftains on a sunny September day out on the studio backlot. Michael Eisner, all six foot four of him, and Frank Wells stood in the gazebo built for Something Wicked This Way Comes and told the assembled multitude they were to be called “Mike” and “Frank” and that they were excited to be part of Walt Disney Productions. They assured everyone that they weren’t looking to lay people off.

And blah, and blah, and blah.

I was young then, and took these assurances to be positive, happy signs. I was, of course, an idiot. New execs coming on board almost always say, “Nobody has to worry about their jobs.” It’s muscle reflex. When the words come out of their mouths, people are wise to begin looking for other work, if only to be on the safe side.

I didn’t know these things then, because I had been living inside the old Walt Disney Productions, where change was incremental, the pace of animated feature work was leisurely, and higher-ups asked one another, “What would Walt do?”

Life at Disney was flowing in a new direction. Mainstream Hollywood had charged through the Cahuenga Pass and now stood poised to turn WDP’s old ways of doing business inside out. Mainstream Hollywood was right there in front of us, smiling out of the Something Wicked gazebo.

Within twelve months, a thousand Disney employees were laid off.

Mouse in Transition has been released in paperback and e-book formats from Theme Park Press. In addition to Hulett’s on-going narrative, the book contains a foreword by Disney director John Musker, a half-dozen interviews with Disney old-timers, and biographical sketches of Disney animation staffers who worked at the studio in the 1970s and ’80s.

.png)