Ottawa Animation Festival 40th Anniversary Look-Back: ‘The Man Who Planted Trees’

The legendary Ottawa International Animation Festival celebrates its 40th anniversary this year.

In honor of that occasion, the festival has commissioned a number of international animation historians, programmers and critics to write essays about each of its grand prize-winning films. In partnership with the festival, Cartoon Brew will present one essay per week leading up to the festival on September 21-25, 2016. We’re starting today with a look back at the winner of Ottawa 1988, The Man Who Planted Trees. For more information on attending Ottawa, visit animationfestival.ca.

Ottawa 88 Winner: The Man Who Planted Trees

Essay by Maureen Furniss

There are a few animated films that blend a mastery of technique, sheer beauty of images, and social consciousness as well as The Man who Planted Trees (1987). This Canadian film, directed by Frédéric Back (1924-2013) and produced by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), was honored by the Ottawa International Animation Festival in 1988; it received accolades worldwide at the time of its release and it continues to resonate with audiences.

Adapting a story by the French author Jean Giono, the film tells the story of the shepherd Elzéard Bouffier, who single-handedly reforested a vast region in the French countryside. The story is told from the point of view of a young traveler, who meets Bouffier and witnesses the miraculous transformation of the land from a treacherous wasteland to a lush paradise. The 20,000 pictures used in the film were created by Back and his assistant, in-betweener Lina Gagnon, who drew every second image.

From a young age, Back had been deeply concerned with nature and the treatment of animals, issues that characterize his most celebrated works. Among them, The Man Who Planted Trees has some of the closest parallels with Back’s own life as a dedicated environmentalist, who went so far as to plant thousands of trees on his own property, in a grove dedicated to Giono. (A detailed website, fredericback.com, details Back’s career as an illustrator, television personality, animator, and activist, and provides an extensive biography that explains how he developed the passions that fueled his life and work.)

When CBC producer Hubert Tison read Giono’s short story, which Back presented to him, he wondered how the story could be adequately translated into animated form, especially in the thirty-minute format that was proposed. The resulting film achieves the translation in a compelling way, with a script that takes the viewer into varied environments, transported through visual storytelling and the use of line, color, form, and movement, culminating in an uplifting and empowering ending. Visual elements are well supported by a soundtrack designed by the accomplished Canadian composer Normand Roger, who has credits on over 200 animated films.

Environments in the film are rendered using colored pencils on matte acetate, which has a frosted surface that was at times varnished clear to allow the use of multiple layers. Pencils allowed Back to create lines and variations in shading that would have been impossible with the then-standard practice of paint on clear cels found at industrial animation studios. Birds and flight play a significant role in structuring the viewer’s experience of the surroundings, taking us into and around the landscape as it changes through time. Individual scenes are connected largely through blending—through the use of cross-fades or mixes achieved through multiple exposures—rather than cuts, which are more abrupt and would break the narrative flow. The narration, read by Canadian actor Christopher Plummer, flows just as fluidly as the images do, imparting the story in a slow and articulately delivered reading.

The film opens with a scene of barren land, images created in blacks and brown. A flying black bird takes the viewer into it, accompanied by Roger’s shimmering score, which recurs at key points in the film to aid transitions. The storyteller then emerges: he is a young man undertaking a trek into unknown and even hostile territory. The camera pans over still images and dissolves into decrepit homes and a broken church, suggesting the physical and moral decay that has beset the region. Rough lines in the images reflect the effects of the relentless winds that the narrator suggests have driven residents mad.

The shepherd, Bouffier, is introduced as a speck on the horizon of this environment, seemingly insignificant. But after the young man approaches him, the viewer sees he is full of life—and not only him, but his dog and sheep, too. The softer, curved lines of these figures contrast with the craggy landscapes of the villages and surrounding areas. Here the color palette changes too, as the shepherd pours life-sustaining water, bringing blue into the otherwise black and brown background. Red, too, is introduced—for example, in the tiles upon the roof of his well-hewn stone home.

His peaceful experience is contrasted with the violent struggles among desperate villagers, whose experience is depicted through spiraling hands, swords, blood, ogres, and madness. This variation is compelling to the viewer, bringing in a sense of danger into the already enigmatic events of the story. It is through such variations that the viewer is kept engaged in the story. Events of World War I are introduced, with violent scenes and disorientation, punctuating the film at its mid-point to allow a fresh start to the storytelling.

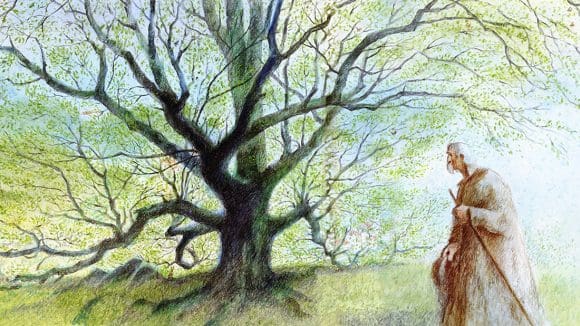

As the story evolves, color becomes varied and more detailed in application. As Bouffier moves through trees he has planted, blues and greens have replaced the browns and blacks that dominated early scenes. One perspective looks up through the trees to the sky, spinning around in a kind of choreographed movement. Young birch trees introduce golden leaves, with a bird flying among them and leaves softly floating. Water flows through rocks, reflecting the visitor’s face and flowers appear, in red, purple, orange, and yellow.

The tone of the film changes dramatically when a government delegation appears, introducing many characters, colors, and forms. They are captured in lively close shots, with the point of view flowing around in a spinning camera, guided by red and blue birds flying through the leaves. Still later, when a forester is invited to meet Bouffier, lines shimmer as if light is falling on them, and trees dotting the hillsides are multicolored and loosely rendered. As they walk through the trees, leaves softly floating in the breeze appear to be white, reflecting a complete transformation from the dark, craggy environment found at the start of the film.

This lightness continues in closing scenes, as the visitor returns to the area, riding in a bus. The camera circles around the traveler, even going outside the vehicle, reinforcing the feeling of lightness and flight.

This perception continues into pictures of the renewed village, in which a moving camera effect combines with dissolves to continue the notion of dance or flight. The movement is punctuated by a young woman, who raises a baby into the air, and birds moving through the scene. Multiple layers of gardens and trees are displayed in close shots, as though we are bursting through them, horses run through the landscape as it dissolves through various scenes of nature, and multicolored images, suggesting springtime and renewal. These images are strongly suggestive of an Impressionist aesthetic, as they are concerned with energy and light.

The film ends by explaining the greatness of this one man and his devotion to make a difference, inspiring the viewer to feel empowered as well. It is easy to compare the shepherd’s work with that of Back, whose life and art were inseparably linked.