Animator Max Hattler Accuses Bassnectar Of Profiting From His Films

When does “VJ sampling” cross over into outright copyright infringement?

Like a DJ or rapper or other music artist who samples the works of other music artists to create something new, VJs (video jockeys) use the works of other artists to create a kind of visual collage, for use in live concerts, clubs, museums, and other venues. And similar to when those music artists whose works were sampled accused the DJs and rappers of stealing their music — Rick James famously sued MC Hammer over the song, “U Can’t Touch This” (they settled out of court) — as VJ sampling becomes more pervasive, similar issues are arising.

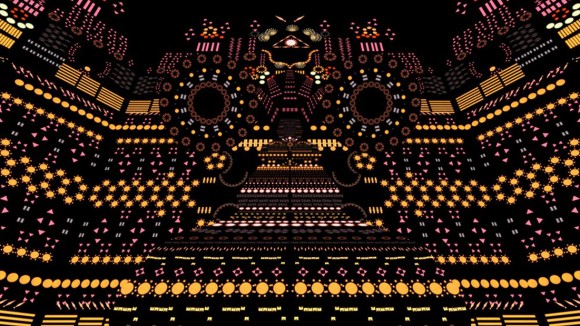

Just ask media artist, animator, and filmmaker Max Hattler, whose work has often been featured on Cartoon Brew. Hattler, whose film Sync was awarded best video installation at Multivision in St. Petersburg, Russia and a special prize at Visual Music Award in Germany, both in 2011, and whose film Shift was awarded best experimental film at the TOFUZI International Festival of Animated Films in Batumi, Georgia, in 2012, among other honors, is known for his kaleidoscopic-verging-on-psychedelic style that creates a rhythmic yet unsettling effect upon the viewer.

It was this style that caught the eye of electronic music artist and DJ Lorin Ashton, creative force behind renowned music and video performance group Bassnectar, whose stage shows are famous for their immersive light displays and visuals. By 2011, Bassnectar was using Hattler’s 2010 film 1923 aka Heaven as visual backdrop to his song, “Rollz – Plugged In”:

In 2013, Ashton’s production team approached Hattler himself, requesting to commission Hattler to produce more VJ loops for Bassnectar to use on tour. The conversations between the parties didn’t lead to any work, but Bassnectar continued to use Hattler’s work anyway — without permission and without compensation to Hattler. From 2013 through 2015, during live performances of Bassnectar’s track “Frog Song,” Bassnectar used Hattler’s Sync as the visual accompaniment:

Even further, RadioEditAV, “a committed collective of directors, cinematographers, live visual artists, designers, animators, VJs, DJs and producers,” provided a visual package to Bassnectar in 2013 that included a work heavily inspired by Hattler’s 1923 aka Heaven:

Hattler, currently a professor at the School of Creative Media, City University in Hong Kong, only recently discovered this unauthorized use of his work and took to Facebook to express his displeasure at the use of his work without his knowledge, permission, or compensation.

Bassnectar responded to Hattler on Hattler’s Facebook page, offering to remove Hattler’s work from his show – but failing to offer compensation to Hattler for using his work for the last six years — and claiming that it is common in the DJ/VJ “culture” to “sample” the works of others, and that the culture is a “frontier of collage art.” He also wrote that Hattler might benefit from the exposure being given to him by Bassnectar: “We give a lot of good exposure to video artists, and it leads to more work for them, often from us.”

To a certain degree, Bassnectar is correct. American copyright law protects what is known as “transformative use,” or “productive use,” that is, the use of another’s protected work where such use “transforms” the original work to produce something new. But where the use of the original work is a mere reproduction of the original, then a case can be made for copyright infringement.

Complicating matters even more, VJ sampling is a relatively new form of creative work, and so the law is murky, making it difficult to determine whether Bassnectar is liable for infringement. Similar to DJ sampling, much will depend on the extent of the use of the copyright holder’s work. In the noteworthy case of Newton v. Diamond, a federal court ruled that the Beastie Boys’ use of three notes of jazz artist James Newton’s work, “Choir,” in their song, “Pass the Mic,” was allowable, reasoning that three notes and six seconds of music was too minimal to find infringement. (And the Beastie Boys had already licensed the sound recording — Newton was suing for use of the composition without permission. Music allows for a copyright in both the sound recording and in the actual composition.) As the videos above evidence, Bassnectar used far more than six seconds of Hattler’s work.

It can be dispiriting when a highly successful artist like Bassnectar, who charges six-figure booking fees per show, so obviously uses the work of an independent artist without permission and without compensation. Bassnectar’s position is especially problematic when he himself insists all Bassnectar fan art that includes Bassnectar’s logo is sold through the Bassnectar Art Exchange, so that he can take his cut.

“[I]f you make art and then take the Bassnectar Logo and sell your art using the Bassnectar Logo, that’s not ok,” the musician wrote recently in a passionate screed explaining to fans that they must pay him if they use his logos, symbols, or imagery in their artwork. “That’s not what a true fan does, that’s not what a bass head does, and that’s not what I would do.” Apparently, using Bassnectar’s intellectual property is not OK with Bassnectar, but using the property of other artists is just part of the DJ and VJ culture.

Cartoon Brew reached out to Bassnectar for comment. He had not responded at the time of publication, but we will update with a response should he choose to respond.