‘There Are As Many Hells As There Are Evil Minds’: Isamu Imamake On Animating The Afterlife In ‘Dragon Heart’ (EXCLUSIVE BTS)

Released in Japan earlier this summer, Dragon Heart: Adventures Beyond This World (Doragon hāto: reikai tanbō-ki) is the fifth collaboration between former animator Isamu Imamake and writer and executive producer Ryuho Okawa.

After starting as an in-between artist, followed by design and animation roles in film and television series, including Neon Genesis Evangelion and Cowboy Bebop, Imamake served as director on The Mystical Laws (2012) and three Laws of the Universe films (2015–2021), based on Okawa’s “Happy Science” spiritual and political beliefs.

“I was in my 20s when I met Ryuho Okawa,” Imamake recalled. “I encountered some of the books he wrote and attended his lectures. At that time, I realized the possibility of animation, of how we can turn anxieties into hope by encountering his books and lectures.”

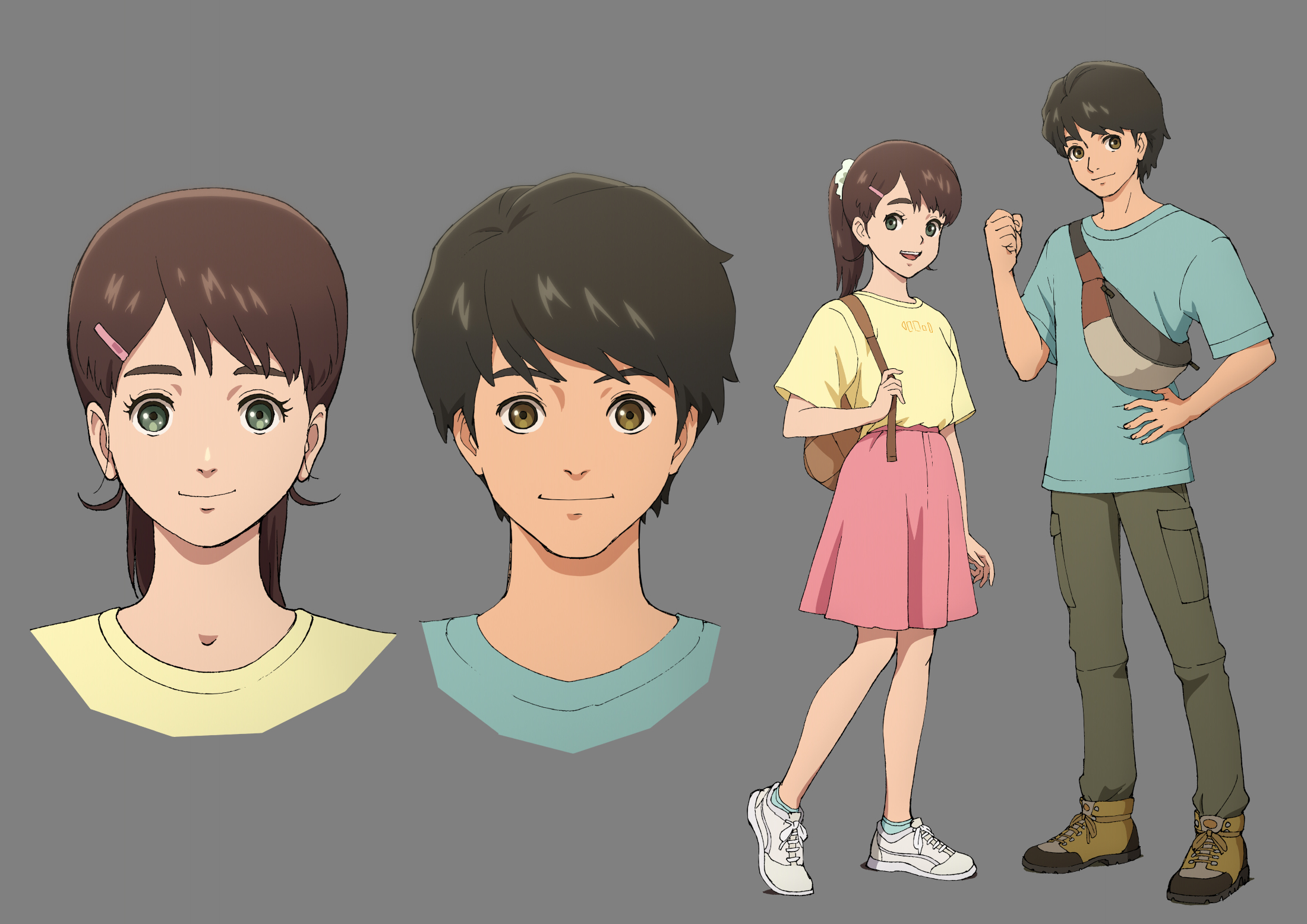

Dragon Heart follows a young Tokyo student, Ryusuke Tagawa (voiced for U.S. audiences by Zach Aguilar), who visits his cousin Tomomi Sato (Ren Holly Liu) in the idyllic countryside of Tokushima. After an accident at a river and an encounter with a giant green dragon, the teens learn from the mystic Amen Hiwashino Mano (Rick Zeiff) that they have died. The story follows the teenagers’ attempts to redeem their young lives by voyaging with the dragon through disparate realms of Hell — including Hells of Fear, Lust, Terrorism, and the Internet — meeting ghosts and demons ruled by the sardonic deity Enma (Brook Chalmers), King of Hell, before they find enlightenment in the holy paradise of Shambhala.

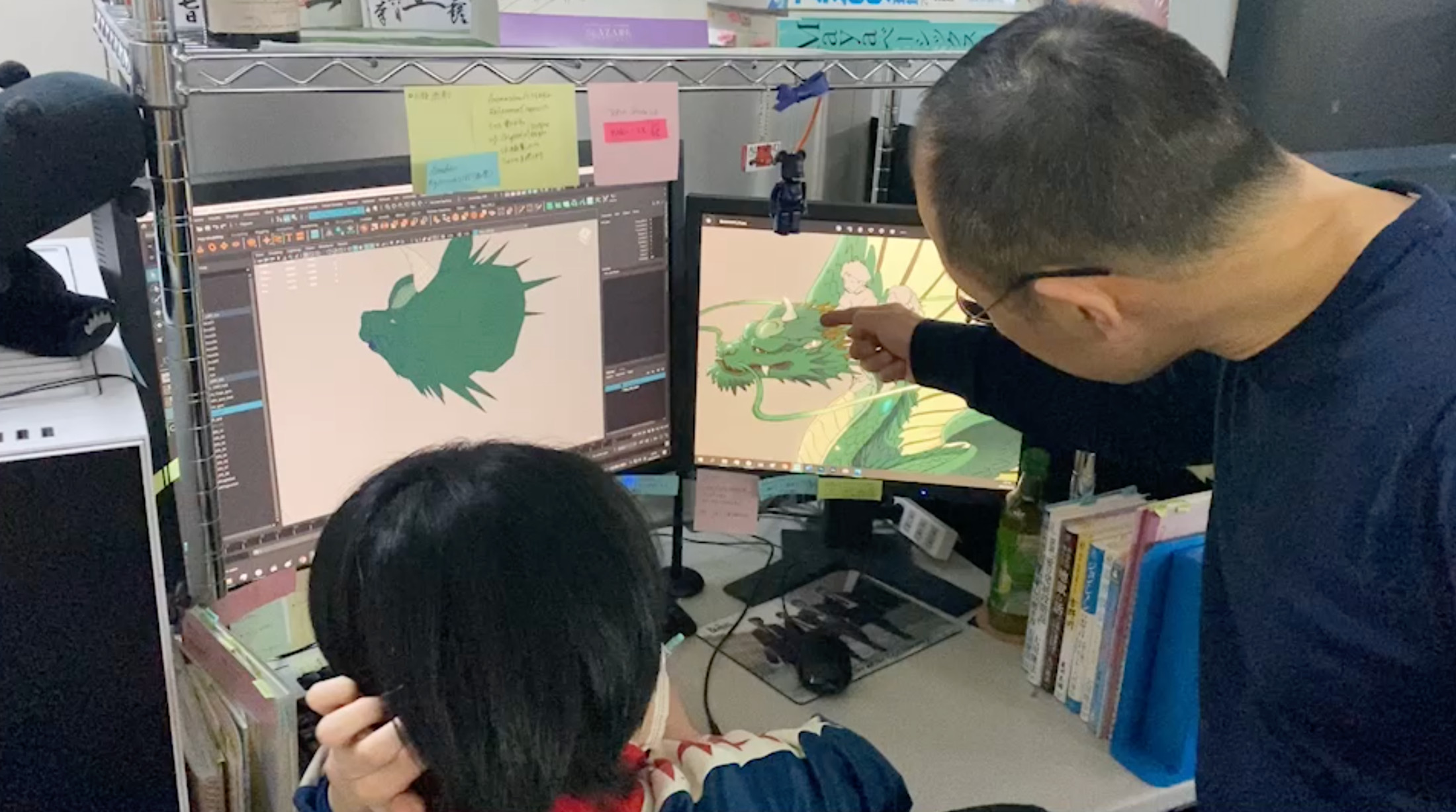

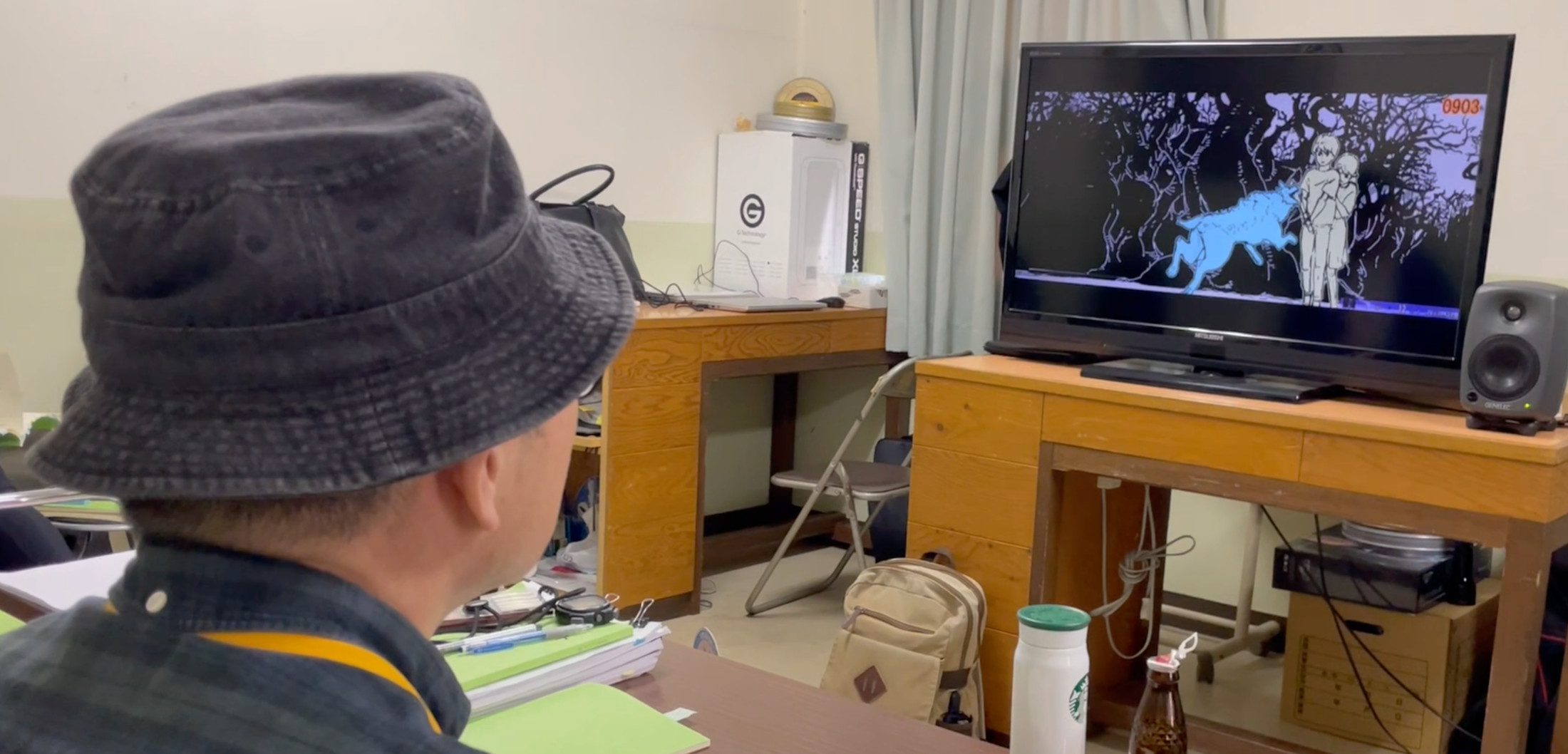

The film features lush painted landscapes and anime-style 2D animation handled by a core team of animators at HS Pictures Studios in Japan, combined with 3D work overseen by VFX creative supervisor Yumiko Awaya. The disparate styles sprang from the story’s philosophies, which Isamu Imamake discussed with Cartoon Brew via a video link from Tokyo, speaking through interpreter Mia Tomikawa.

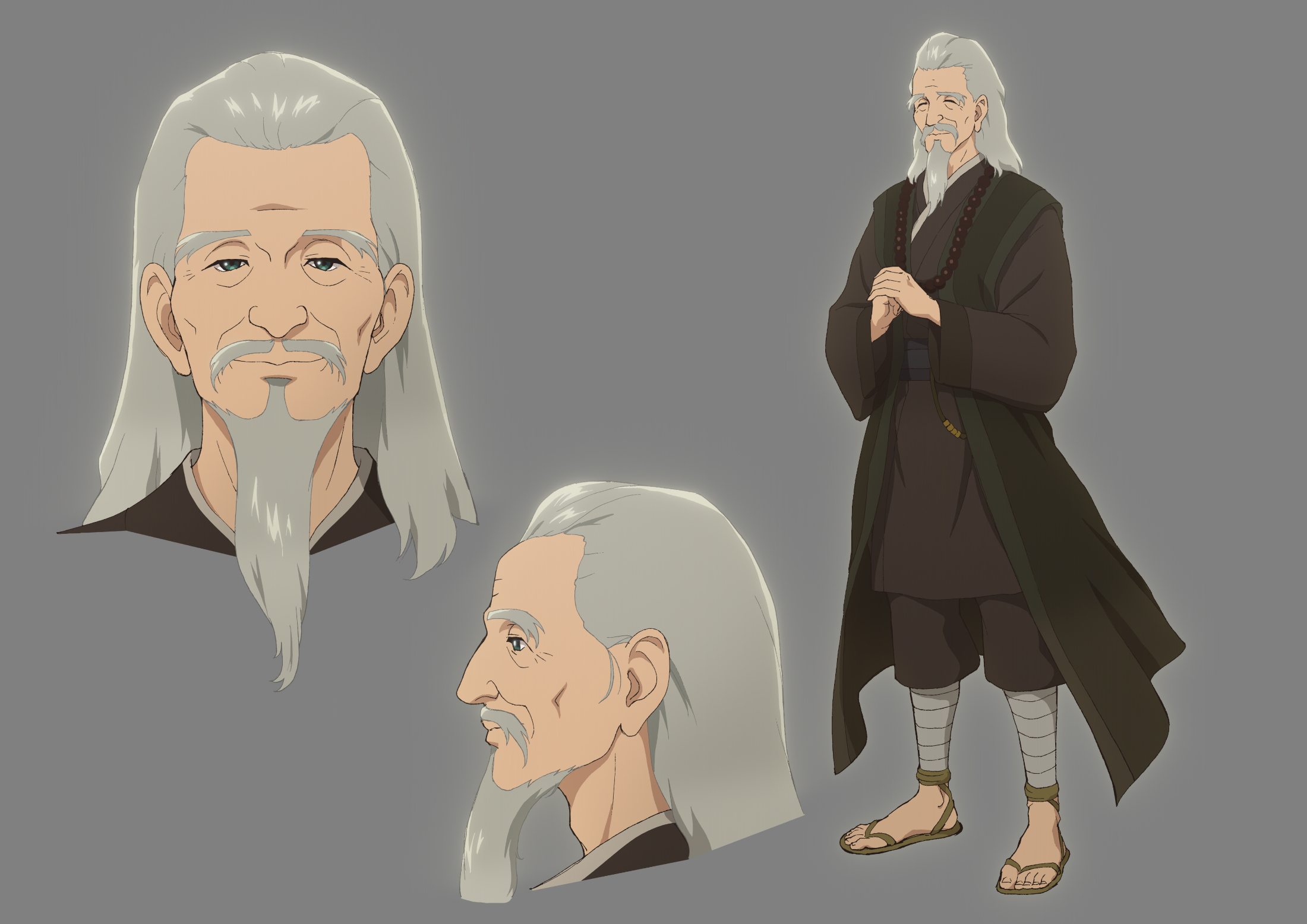

Cartoon Brew: The human characters of Dragon Heart have an anime feel, while other characters appear to be drawn from mythology and religious iconography. What inspired your character design choices?

Isamu Imamake: When I first read Okawa’s original story, I felt like I went on a journey with Ryusuke and Tomomi. I cherished that image and tried to portray their figures based on that [idea]. I designed the characters because I wanted to incorporate the Japanese animation style. I designed the dragon based on traditional sculptural structure and Buddhist paintings. I wanted to portray this world as inhabited not only by humans, but animals and invisible beings that even include aliens.

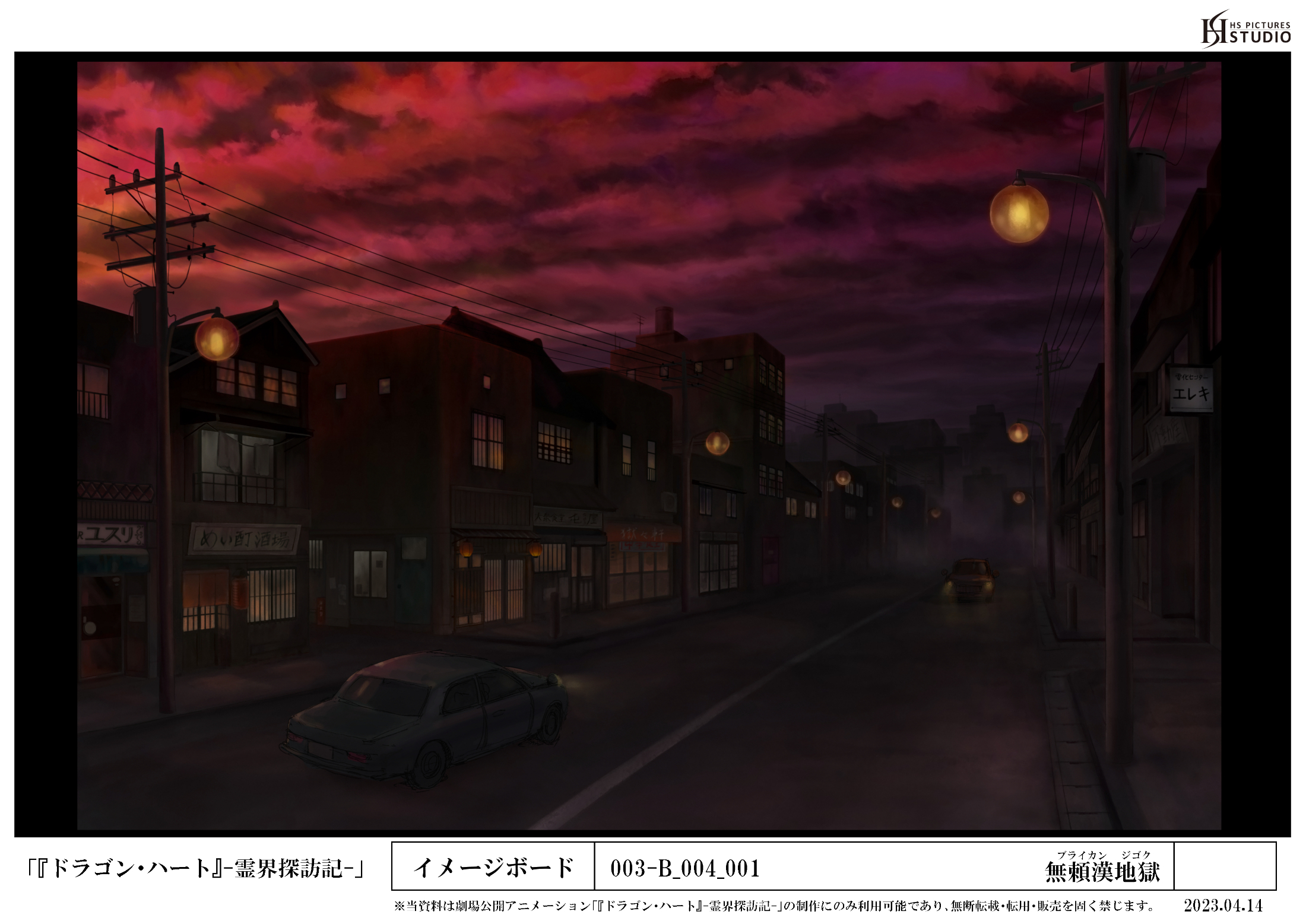

There are many contrasts in settings — a sterile look for early scenes in Tokyo, then the lovely forests of Tokushima, and the mad realms of Hell. How did you decide on rendering styles for those different environments?

My main theme was to portray a beautiful world. If you portray nature as-is, it’s sometimes difficult to convey [its] beauty. We also portray Hell as a wild world of violence, [but] I thought that it was not enough to see Hell from the perspective of this world only. It was necessary to take on a perspective from the spiritual world to portray the worlds of Hell, as well as the beauty of Tokushima. I wanted our artists to feel the love that surrounds us, and I asked them to look at the beauty of nature. I also wanted them to see the worlds of Hell from a perspective of love, to see people [there] who are filled with fear and who have done bad deeds, from a perspective of love.

One of your most mystical characters is the dragon, who doesn’t speak but feels wise. How did you decide to articulate him nonverbally, including his bond with the shaman Ameno Hiwashino Mikoto?

I did research on traditional Japanese dragons. We also discussed how the dragon should be verbal or nonverbal. Our understanding was that this green dragon was a guardian who had resided in the Anabuki River for a long time. The Anabuki River and the Yoshina River that you see in the film are located near Mount Kotsu, where there is a shrine. In that shrine, Hiwashino Mikoto is enshrined. He is an old deity of Japanese myth, and he has been protecting that region for a long time. This story is the spiritual adventure of Ryusuke and Tomomi, who are protected and guided by this dragon, their guardian, and Ameno Hiwashino. When the dragon awakens for Tomomi and Ryusuke at the river, he has been waiting for them for thousands of years to help them go through their spiritual journey. So, I thought that words were unnecessary when the dragon awakens. To design the dragon, it was basically hand-drawn, but we also used 3D. We had a choice of 3D or hand-drawn, but when I considered how to express the dragon’s expressions and movement, we chose to use only hand-drawn animation.

How did you keep creative control of your 2D and 3D mediums?

First of all, I needed our main animators to portray both this world and the other world. I believe that animation is about expressing the world of our mind. So, I wanted our animators to express what they were thinking in their minds. Of course, it is also possible to do that using 3D animation; however, I thought that it might take a little bit more time, but it was better to use hand-drawn animation to portray the world of the mind. We used lots of visual effects in the scenes of Hell. For example, in the scene where we hear the song “From Hell to Hell,” we used techniques of motion blur and other 3D technologies. [VFX creative director] Yumiko Awaya had a team overseas, and they were very versatile and skilled with 3D images.

Your visions of Hell include modern hang-ups, like terrorism and the Internet. What inspired those concepts?

In my research, I found that perspectives of Hell depend on religious beliefs of different countries’ cultures. I believe that Hell is a world that is created based on our mind and our actions while we are living in this world. I also did meditation, and I found “Hellish” tendencies within my mind. From that perspective, I saw lots of worlds of Hell that existed in this world. For example, in the Hell of Villains, which was based on a 1960s town in Japan, I looked into my own feelings of fear and I imagined how people full of fear express themselves with violence with destruction. That was also based on movies and news that I saw in everyday life. When I tried to portray Hell, I wanted to look at the “good mind” that we take in our daily lives. When we retain a good mind, we take on “heavenly actions,” and Heaven manifests around us. This movie portrays how there are as many Hells as there are evil minds. But there are as many worlds of Heaven as there are good minds. I contemplated rules that govern both worlds and incorporated those into each specific Hell, such as the Hell of Lust or Internet Hell. In Internet Hell, it’s a world of thoughts sent out from each person.

You portrayed King Enma, the King of Hell, in an interesting way with a modern Western wardrobe. Why was that?

It has been said that the idea of King Enma has come from China and India. He serves as a judge of Hell, judging which world of Hell people will go to. I designed him based on the premise that King Enma is an enlightened being. But many people in the modern world do not know the existence of Hell. These people have done many crimes, deceiving or hurting people, which they don’t recognize as crimes. In our film, King Enma is fed up with his job because so many people come to his world, not knowing what they have done. So, he took on the character of a modern figure, wearing sunglasses and an Aloha shirt with a tennis racket in his hand. And, to show he is an enlightened person, I had lotus flowers printed on his shirt.

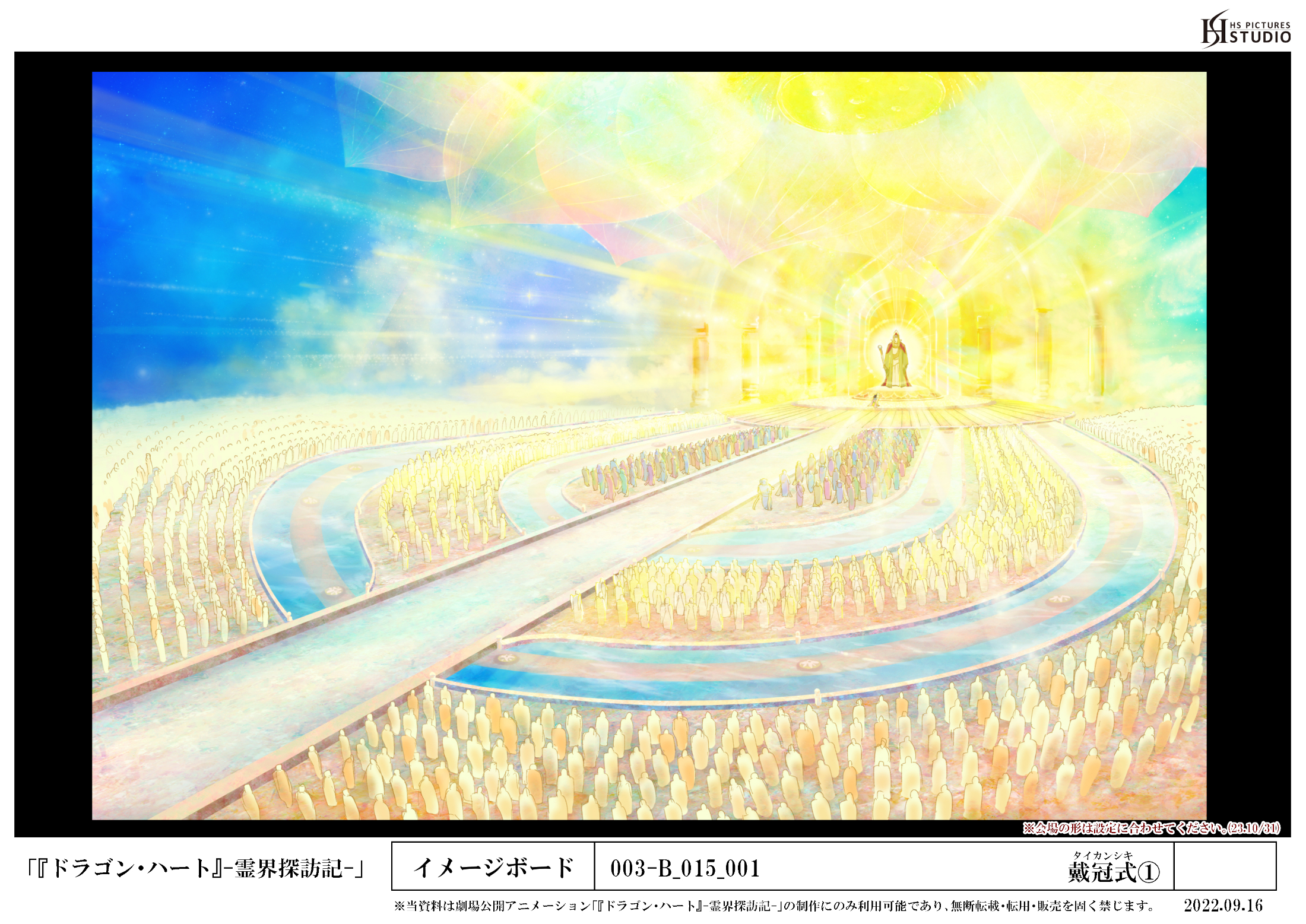

There are many images derived from Tibetan lore, including your climactic scenes of Shambhala. Can you explain how you envisioned your concepts for that world?

We portray Shambhala as the spiritual center of the Earth. People go through religious disciplines there to build a bright future for the people of the world. Many types of people go through those disciplines — hermits, politicians, teachers, religious people. The basis for those images were the books of Mahāyoga.

How did you design your final ecstatic scenes with the appearance of Vishnu and other deities in the congregation at Shambhala?

I referred to the song “Shambhala” [one of several written by Ryuho Okawa for the film]. According to this song, Shambhala is a place where only a select few can enter to go through disciplines, to raise the level of [their] enlightenment to go to a higher dimension. But Shambhala is a place in Mount Meru, where people from all over the world come together to go through disciplines to improve the world. Those who attend the coronation ceremony have gone through many disciplines. They are divine spirits, gathered to honor the great light of Earth. God Vishnu represents the different gods of India. I believe the spiritual center of the Earth protects us with great love to guide us. So, we included many practices to portray this great spiritual center.

Why is the auditorium shaped like a lotus flower?

In Buddhism, the lotus flower symbolizes enlightenment. I also learned that the shape of Mount Meru looks like a lotus flower. I used the design of the lotus flower to express how this is a place gathered by enlightened beings.

.png)