‘The Boy And The Heron’ Reviews Roundup: Hayao Miyazaki’s Latest Gets Unanimous Praise After International Premiere

Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron received its international premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival last week, and Western critics are beginning to chime in on what may be the director’s final feature.

Reviews could prove an important factor in how The Boy and the Heron’s performs with wide U.S. audiences. The die-hard fans will show up regardless, but Studio Ghibli has boldly refused to do any promotion for the film, and its U.S. distributor, GKIDS, has been minimalist in its promotion. There is a brief teaser, a few stills, and a vague synopsis written in poetry form:

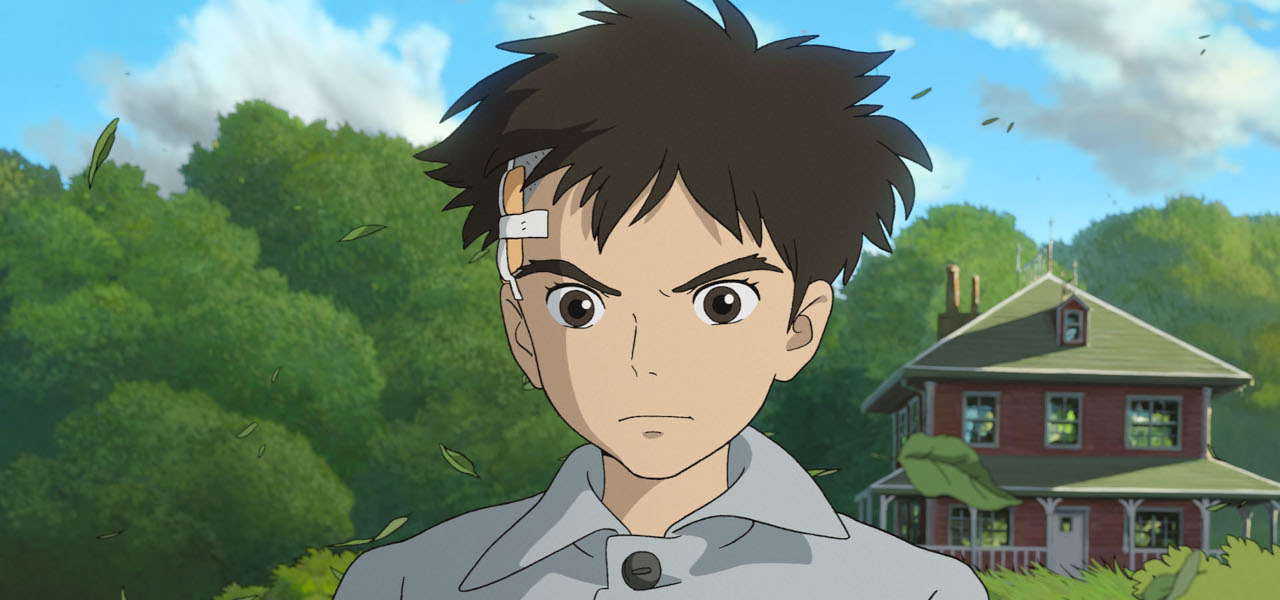

A young boy named Mahito

yearning for his mother

ventures into a world shared by the living and the dead.

There, death comes to an end,

and life finds a new beginning.

A semi-autobiographical fantasy

about life, death, and creation,

in tribute to friendship,

from the mind of Hayao Miyazaki.

In the spirit of keeping audiences mostly in the dark, we’ve tried to be as spoiler-free with this reviews roundup as possible. We’ve only included snippets that don’t contain plot details.

We read more than a dozen reviews, checked the scores on a dozen more, and they were all full of admiration for the film. There were some niggling issues – the words overstuffed and complicated appeared more than once – but in each case, the critics were happy to overlook the drawbacks.

The most common virtue cited among the critiques is that the film is visually stunning. There’s no unkind word in any review we saw about the animation in The Boy and the Heron, with many reviews saying it’s the best in any Miyazaki film.

Here’s a closer look at what critics are saying about Miyazaki’new effort:

Brian Tallerico at Rogerebert.com compared the film to Miyazaki’s other work:

The Boy and the Heron clearly plays with themes that Miyazaki has explored before with echoes of Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro, Howl’s Moving Castle, and more, but this is no mere greatest hits. It’s the work of an artist reflecting on a career. Without spoiling anything—and I’ll go into greater depth in a full review when it releases in December—this story is about acceptance, redemption, and the power of creation. It’s a film that somehow recalls Alice in Wonderland and Miyazaki’s own life simultaneously.

Vulture’s Alison Willmore noted differences between The Boy and the Heron and Miyazaki’s previous work, but justified it, explaining:

The Boy and the Heron is irresistible in its dream logic, straddling the adorable (white blob creatures called Warawara that inflate like balloons) and the dark (parakeet soldiers that are on the search for fresh meat). But what makes it most compelling are the ways in which the real and the magical are equal presences. The magical universe may be a means of evading a reality that’s on fire, but it’s not without its own ugliness, all of it brought in from the outside by those looking to escape. If The Boy and the Heron ultimately feels less universal in its emotional appeal than past Miyazaki work, it’s only because Miyazaki is grappling with something very specific — that we can’t leave the world behind when we’re a part of it.

Peter Debruge at Variety enjoyed the film, but wished it had deviated more from the Miyazaki formula:

True to form, The Boy and the Heron proves unpredictable, but it’s also within the realm of Miyazaki’s earlier work, which is both comforting and slightly disappointing. He hasn’t done anything to tarnish his filmography. Nor has he expanded it in the way Spirited Away did. The Heron is an unpleasant yet detailed character, right down to the guano he leaves in his wake. That contrasts with dozens of rudimentary, half-anthropomorphized parakeets — pink, green, yellow, and blue birds with beady eyes and bulbous nostrils. (These are not Ghibli creatures people will be getting tattoos of anytime soon.) The movie is full of visual ideas, from a swarm of frogs to the busybody maid who becomes a warrior pirate on the other side, but it mostly reminds how familiar our world already is with the one Miyazaki’s been weaving all these years.

In his review for Indiewire, David Ehrlich wrote:

If The Wind Rises was a woundingly piercing work of self-examination, The Boy and the Heron is, by contrast, a crushingly poignant work of self-elimination. Once more, Miyazaki is questioning the purpose of artistic creation in a world so prone to ruin, but this time, he’s asking it of us. Why do we do anything when everything seems to be crumbling before our eyes, and how do we find the strength to do it? If Miyazaki knew the answer, he would have told us by now; he wouldn’t have felt the need to devote the twilight years of his life to a painstakingly animated movie that he feared he wouldn’t be able to finish before war — or death by any other means — rendered the whole project a waste of time. It’s not, “What will we do without Miyazaki’s genius?,” but rather, “What will we learn from the legacy of his failure?”

The Hollywood Reporter’s David Rooney was floored by the film’s animation:

We’ve come to expect transfixing imagery from Miyazaki, a holdout champion of hand-drawn animation who has mostly resisted the form’s predominant shift to CG, other than for enhancement purposes. But even by his own standards, The Boy and the Heron looks astonishing, from the lush green landscapes of its principal rural setting to a field of flowers in the breeze to the gentle rays of morning sun peeking over the architectural grandeur of the protagonist’s home.

Virtually every impeccably framed composition could be a distinct work of art, with painterly backgrounds so gorgeous in their colors and textures they invite the viewer to get lost in them. Then there’s the exacting attention to foreground detail and movement, all of it stitched into fluid visual storytelling in which even the oddest elements cohere into a harmonious whole.

.png)