How To Get Millions To Watch Your Short Film On Third-Party Youtube Channels

Third-party Youtube channels like TheCGBros and CGMeetup are becoming an integral part of many short films’ release strategies. The ultimate display of this trend was last year’s Academy Award-nominated One Small Step, whose creators opted for a CGMeetup premiere that resulted in 16.9 million views (and counting).

With these aggregation channels’ popularity rising, Cartoon Brew decided to investigate the way they function. Do the channels scout films that are already online, or can you plan a premiere together? Do they ask for exclusivity? Do you get a screening fee? Is a certain number of views guaranteed?

We conducted email interviews with TheCGBros’s owners, as well as the creators and rights holders of five different shorts, all of whom have successfully taken this route when publishing their film. From their comments, we gleaned seven key stages to consider when preparing your own short’s release. (CGMeetup did not respond to multiple requests to participate in this piece.)

1. Approaching, or getting approached by, the channels

Both TheCGBros and CGMeetup mainly showcase independent animated shorts, and curate their channels in order to present a unified brand. When asked how this curation works at TheCGBros, co-founders Shaun and Bill Johnston share that their half a dozen staff members “regularly search online, as well as through screenings of film festivals and other competitions.” When they discover a short that would fit their brand, TheCGBros sends its rights holders an “invitation to stream.”

Lucy Xue and Paisley Manga from the U.S. received such an invitation from both TheCGBros and CGMeetup. They were spotted on Vimeo, where they released their student short Course of Nature in 2016, gaining 21,000 views. Mere weeks later, Course of Nature racked up 7.5 million views on CGMeetup, and a staggering 19.3 million on TheCGBros.

Some schools and studios have established connections with the Youtube channels. The Animation Workshop in Denmark, for example, regularly approaches both to re-upload their students’ films, as Michelle Ann Nardone (director of animation and cg art) confirmed. Often months, and sometimes years, elapse between the school’s original upload and the channel’s, but neither of them mind. From the rights holders’ perspective, Nardone explains that it simply “gives the films another round of life on Youtube.”

But you don’t have to wait to get scouted, nor depend on your school’s policies. TheCGBros stated that many of the films they showcase actually came to them through their website form. (CGMeetup has a similar form.) Once you’ve submitted the form, TheCGBros first “screens videos based on Youtube’s acceptance criteria (appropriateness — i.e. pornography, language, violence, etc).”

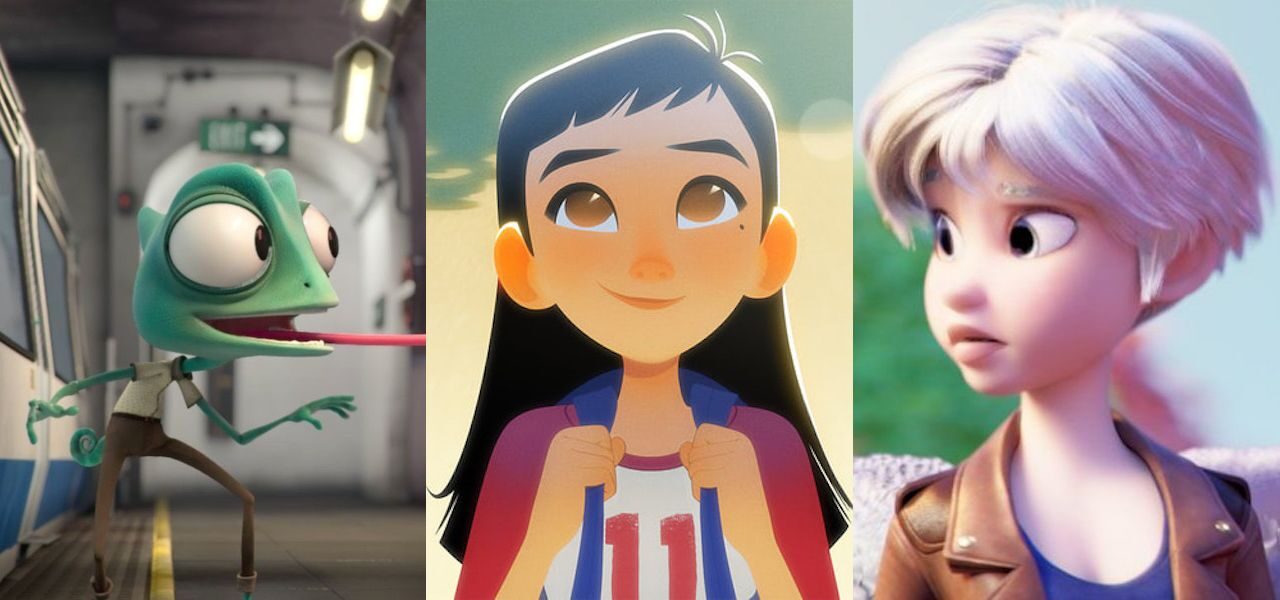

Then TheCGBros’s criteria follow, evaluating the short’s technical aspects and production values, as well as storyline, continuity, and character development. All of this finally translates into a rating: “shorts must score a minimum of 3.5 out of 5 to be accepted.” Both CGMeetup and TheCGBros publish mostly cg animation, as their names would suggest, but 2d shorts are featured every now and then too.

2. Getting your film seen by large audiences

Most filmmakers release one short every few years at most, which makes it impossible for them to build a considerable Youtube following. TheCGBros’s co-founders explained that nowadays, a short’s “findability cannot be obtained effectively at an individual level — only at a global or ‘systems’ level… For a film to be seen, it must, first, be found.” And that’s where these third-party channels come in: they serve as a kind of cinema to the general public, and a distributor and publicist to creators, as TheCGBros describes it.

Of course, there are many possible platforms to reach audiences, but it can’t be denied that Youtube is today’s biggest. With a combined seven million subscribers, TheCGBros and CGMeetup have a steady group of viewers to reach out to. Last year, Jenny Harder, from Germany, garnered 1.2 million views on TheCGBros and 4.3 million views on CGMeetup with her short Being Good. On Vimeo the same short hit a considerably lower 9,000 views. Harder says she uses the different platforms equally, but finds that “bigger channels on Youtube with a lot of followers usually have a greater impact in reaching people.”

3. Actively pushing the release

Despite CGMeetup’s and TheCGBros’s huge followings, an upload in itself is no guarantee of going viral. Or as TheCGBros’ co-founders themselves put it: “The simple fact is that no channel can guarantee views, unless they are illegitimately buying them.” However, there are some strategies TheCGBros has developed regarding the date and timing of the release, as well as the use of certain thumbnails and text to ensure the best response to a short’s premiere.

An extensive social media push can boost chances too. For example, crew members can post on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Reddit, but also specialist websites who feel invested in your project or you as a creator. According to Harder, “having lots of partners that share and promote your work can really make the difference. For example, we had great support from [online professional platforms] Artstation and Artella. And our team of 80 well-connected people was doing great sharing and uploading our film onto several pages and platforms.”

Looking back at Course of Nature’s online release, its directors Xue and Manga admit to “being a bit shy about sharing our work initially, due to lack of experience when it came to social media. As more experienced professionals now, we’d be a lot more confident when it comes to sharing and promoting our work. We would also probably put a lot more effort into other ways to generate revenue or build a fanbase around our work by creating merchandise, promotional images, etc.”

Myra Hild, from Denmark, released her student short Ur Aska online last year. She says it was “coordinated with all the other teams from the school [The Animation Workshop]. There was a lot of thought put into it,” resulting in 323,000 views, which is solid but not optimal. “My experience with posting online is that it’s so much luck,” Hild adds. “Even with the best of strategies, there’s just no guarantee how successful a short will be online.”

4. Getting yourself seen by the industry

While the majority of TheCGBros’s subscription base is “general audience,” it’s also partly industry: cg and vfx studios, software companies, advertising agencies, video game studios, movie studios, etc. Getting this kind of traction gives your work and skills exposure, which The Animation Workshop’s Nardone says is especially important to graduates as they enter their career.

Course of Nature’s Xue and Manga pressed the upload button the very same month they graduated from Ringling College of Art and Design. “It did help us get some freelance jobs,” the artists say, “and we were surprised to find that when we tabled at events, random people there would recognize our work from having seen it online previously.”

Harder’s Being Good was created as a proof of concept for a potential feature film, and its team consisted of 80 international professionals working on the short in their spare time. “A lot of our team members got contacted with job offers because of the film,” Harder says. “I was offered an art director position in animation shortly after the release. We also got to pitch Being Good several times as a show/film, amongst others to Netflix.”

5. Considering an offline release window

When Darrel, by Spanish filmmakers Marc Briones and Alan Carabantes, was published on CGMeetup to 5 million views in 2018, it had already garnered 140 festival selections and 35 awards. A successful festival run doesn’t necessarily translate into a successful online release — Briones and Carabantes said that equal success in both worlds is pretty much “a coincidence” — but it can result in prize money and industry acknowledgement. On top of some festivals’ exclusivity requirements, sales agents usually request one or more years of exclusivity in order to sell to tv channels and the like.

Weighing up the pros and cons, many filmmakers opt for six months, one year, or two years of exclusivity. The team behind One Small Step — Andrew Chesworth, Shaofu Zhang, and Brandie Braxton of Taiko Studios in the U.S. — had a very specific goal for their short: the Oscars. “We showed exclusively at festivals and private events until September 2018… The value of this seemed to outweigh the short-term benefit of simply putting it online.” After the Oscar-qualifying period was over, the short continued to screen at venues and within licensing agreements while living online.

When agreements around One Small Step required the short to be exclusive for a few months, the team would take it offline, then make it public again once this period was over. While their strategy resulted in both online and offline success (with 69 festival selections and 31 awards), they do say that a window of exclusivity is a very real dilemma — especially for “new voices and independent creators who can’t afford to sit on their completed work for extended periods of time when it affects their livelihood.”

6. Earning advertising revenue

Youtube channels like CGMeetup and TheCGBros usually earn money through advertising revenue, but out of our five case studies, four offered their shorts to the channels for free. Being Good’s Harder says money was “something we thought about, but considered not incredibly important to us at that point. We had paid all related festival costs already and never really intended to make money with the short. It was a passion project.”

When asked about a possible fee or sharing of ad income, Course of Nature’s Xue and Manga said they “were both inexperienced students at the time and didn’t even consider that an option for negotiating.” Looking back, the artists say they “might have done things differently now.”

While the channels do negotiate financial compensation every now and then, most shorts get published without anything of the sort. When asked about this, TheCGBros stated that they operate on an advertising-supported revenue model, and that in this revenue model, “the funds we need to allow us to provide our services come from advertising revenue.”

The channel’s co-founders acknowledged that many people “have asked us why we do not share [our] revenue with those who submit videos to us.” In the world of Youtube, they pointed out, virality is not synonymous with financial success. They added, “Youtube connects our channel to paying advertisers and shares advertising revenue with us on a commission basis when viewers watch the ads that Youtube places on the videos. If viewers watch the videos but don’t watch the ads, no payment is generated. As a result, sometimes we realize monetization, sometimes not… We never know in advance what will happen.”

One Small Step’s team say that they have different licensing agreements with different parties, and that these are negotiated case by case. The deals “vary based on each partnership and can’t infringe on each other. Our film wasn’t designed to make excessive money. It was meant to be a calling card for our studio, a symbol of the type of work we are capable of and aspire to create. It’s best if as many people can see it as possible.”

7. Deciding on online exclusivity

Out of the five case studies in this article, three shorts are available on both TheCGBros and CGMeetup, and two on CGMeetup only; three were published on the rights holders’ own Youtube channel as well; and all the rights holders published their short on their own Vimeo channel. The exclusivity of use is always up to you as the rights holder, says TheCGBros.

Which leads to the question: is it better to have your film on more channels? If you have a shared income deal with a third-party Youtube channel, uploading the film onto your own channel might take away from that. Another reason for limited distribution, Ur Aska’s Hild adds, is that “as a creator it’s nicer if views are mostly counted in a limited number of spaces, since it gets hard very fast to get a feeling for how widely spread the film is.” But when going for sheer viewing numbers, it seems best to take advantage of as many platforms and channels as you can.

One Small Step’s team made the decision to post their short on their own official Youtube channel too, for clear-cut brand association. In order to still keep a clear overview, they upload their projects to their official Vimeo and Youtube channels, then share those links on other platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Reddit. For them, this has the extra benefit of making it “simpler to manage if they have to be made private again due to licensing agreements.”

If there’s an overall takeaway from these case studies, it’s that there’s no one best way to reach your prospective online audiences. As One Small Step’s team says, it all depends on “what’s best for the film’s opportunities and the crew’s needs at the time of completion.” As all these shorts’ strategies show, that means something different for every film.

.png)