‘Aladdin’ Writer Unhappy That He Was Excluded From And Not Paid For Disney’s Live-Action Remake

Next May, when you buy a ticket to see the “new” Aladdin, it might be worth remembering that the animation artists and writers who created the Disney characters and stories aren’t receiving anything for their efforts, not even a t-shirt. It’s all perfectly legal, and it’s an example of how animation creators have less protections in the film industry than any other group working in Hollywood.

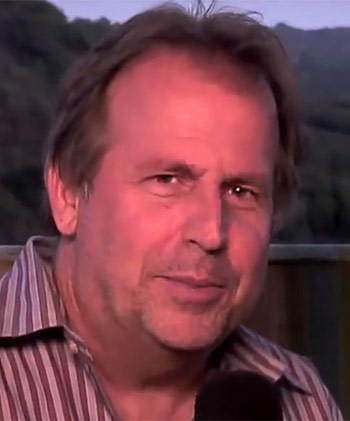

Terry Rossio, one of the writers of Disney’s 1992 animated feature Aladdin, is speaking out about being excluded both financially and creatively from the upcoming live-action Disney remake, which uses stories and scenes that he helped to create.

Rossio wrote on Twitter last Friday, “So strange that literally the only words spoken in the new Aladdin trailer happens to be a rhyme that my writing partner and I wrote, and Disney offers zero compensation to us (or to any screenwriters on any of these live-action re-makes) not even a t-shirt or a pass to the park.”

Rossio, who co-wrote the screenplay for the original animated film with writing partner Ted Elliott and directors Ron Clements and John Musker, is in the current situation because The Animation Guild, I.A.T.S.E. Local 839, which has traditionally represented animation writers, hasn’t been able to negotiate the same comprehensive benefits for screenwriters as the Writer’s Guild of America, which represents live-action screenwriters. If Aladdin had been a live-action film and Disney was remaking it in any form, Rossio would have almost certainly been a profit participant in the remake.

Though his situation is uncommon for screenwriters, it’s undoubtedly familiar for any artist working in animation. The Animation Guild represents all the Disney animation artists who created the original film, and none of the original artists will receive additional compensation for the remake either.

In a subsequent tweet, Rossio readily acknowledged the unfairness that affects everybody in the animation business, saying, “I must hasten to add that screenwriters can’t complain too loudly in the animation field. The original storyboard artists, head of story, character designers and animators did not get even as good a deal as the writers, despite being the heart and soul of the process.”

Rossio, who also been a writer on high-profile films such as Shrek, Treasure Planet, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest, and The Lone Ranger, makes a good point. In animation, you are paid just once for what you create, but corporations continue to exploit the work for decades on end. Not only has Disney already made hundreds of millions of dollars in profit on the original film, but they will now generate hundreds of millions more without having to pay the people who created the original content, which is beloved and popular enough to merit a remake 27 years later.

“[W]hen the work is re-made into a (potential) billion dollar film, why not give the original writers (and storyboard artists) some small participation,” Rossio concludes. “It’s not about compensation, it’s decorum. Consult with the writers, pay a fee, give park tickets. Zero involvement and zero recognition seems gauche…It’s more a lack of recognition … a remake payment, a chance to view the film, inclusion onto the team, a pass to the park — one cannot presume generosity, but lacking anything at all seems gauche.”

.png)