Walt Disney Was No ‘Gender Bigot’

While we’ve already debunked Meryl Streep’s accusation that Walt Disney was a “gender bigot,” let us use her comments as an opportunity to dig even deeper and find out what actions Disney actually undertook to encourage the advancement of women at his studio.

The answer to that question lies in a speech that Disney gave to his company’s artists on February 10, 1941, during which he explained that the studio would begin to train women artists. Below is the relevant excerpt from the speech, which can be found in Walt Disney: Conversations. The emphasises are mine:

Another ugly rumor is that we are trying to develop girls for animation to replace higher-priced men. This is the silliest thing I have ever heard of. We are not interested in low-priced help. We are interested in efficient help. Maybe an explanation of why we are training the girls is in order. First, I would like to qualify it with this—that if a woman can do the work as well, she is worth as much as a man.

The girls are being trained for inbetweens for very good reasons. The first is, to make them more versatile, so that the peak loads of inbetweening and inking can be handled. Believe me when I say that the more versatile our organization is, the more beneficial it is to the employees, for it assures steady employment for the employee, as well as steady production turnover for the Studio.

The second reason is that the possibility of a war, let alone the peacetime conscription, may take many of our young men now employed, and especially many of the young applicants. I believe that if there is to be a business for these young men to come back to after the war, it must be maintained during the war. The girls can help here.

Third, the girl artists have the right to expect the same chances for advancement as men, and I honestly believe that they may eventually contribute something to this business that men never would or could. In the present group that are training for inbetweens there are definite prospects, and a good example is to mention the work of Ethel Kulsar and Sylvia Holland on “The Nutcracker Suite,” and little Retta Scott, of whom you will hear more when you see Bambi.

This is the earliest instance I’ve ever seen of an animation executive articulating that women should have equal opportunities as the men to contribute creatively to the production of films. Reading between the lines, I think it’s safe to assume that Disney’s launch of a training program for women had been considered an affront to the studio’s male-dominated creative staff. Disney, therefore, took a courageous stand by telling employes that not only would he continue the training program, but that women would eventually contribute things that “men never would or could.”

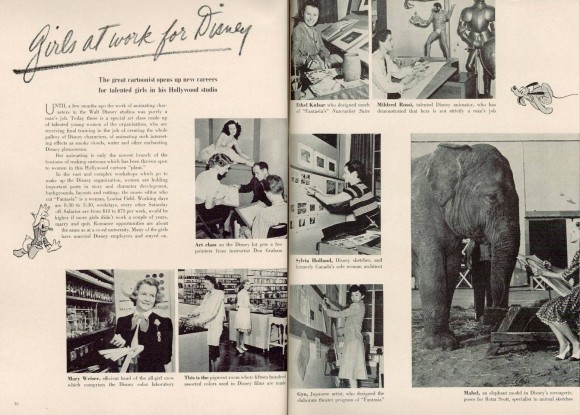

Disney wasn’t merely playing lip service to the notion of promoting women into creative positions. Shortly after he made the speech, in May 1941, Glamour published a two-page spread entitled “Girls at Work for Disney,” that featured photos of some of the women who were “holding important posts in story and character development, backgrounds, layouts, and cutting.” The author of the piece (and keep in mind this was a women’s magazine) wrote, “Salaries are from $18 to $75 per week, would be higher if more girls didn’t work a couple of years, marry and quit,” and continued, “Romance opportunities are about the same as at a co-ed university.”

Walt’s forward-thinking initiative resulted in dozens of women being promoted into inbetweening and assistant animation throughout the 1940s. Disney historian Hans Perk has suggested the following numbers:

“I had a look at who was at the studio in March 1945, and I counted 81 (yes, eighty-one) women at in the animation building alone!!! If we count a handful secretaries, assistant directors and stenographers, we are left with maybe as many as 50 or 60 ladies pushing pencils!”

Even if Perk’s estimates are overly generous and we cut them in half, that still amounts to dozens of women who had moved out of ink-&-paint and into the animation department—and that’s just in the year 1945!

None of this is to say that the Golden Age of animation was a welcoming place for women. On the whole, there was an industry-wide bias against women, a bias that could be traced to much larger cultural forces dictating the role of women in society. But the history of women in animation is also far richer than has been documented in any history book to date. Historians have had a tendency to highlight a handful of the better known female artists of the period, without acknowledging the dozens, and possibly hundreds, of women who held creative roles during that era.

In the earlier post about Meryl Streep’s comments, I listed the names of 25 women who worked at the Disney studio between the 1930s and 1950s. It is, as far as I’m aware, the most complete listing of non-ink-&-paint artists at Disney that anyone has ever compiled, and frankly, it’s just the tip of the iceberg. Much more research remains to be done about the role of women at Disney, and the time to do it is now.

(“Girls at Disney” image from the Disney History blog)

.png)