5 Forgotten Pieces Of Animation Technology That Used To Be Essential For Making Cartoons

The Grohmann Museum at the Milwaukee School of Engineering may sound like an unlikely place for an animation exhibit, but currently there’s a must-see exhibit running there through the end of April that any animation aficionado should run to see.

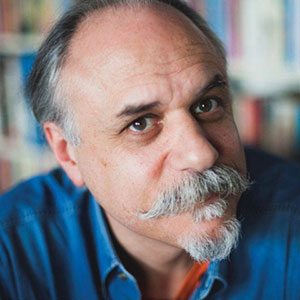

“The Art and Mechanics of Animation: The J.J. Sedelmaier Collection” chronicles the the invention and development of animation equipment throughout the 20th century. The exhibit is organized by J.J. Sedelmaier, owner of the eponymous White Plains, New York commercial animation studio that has animated projects like MTV’s Beavis and Butt-Head series and Saturday Night Live’s “The Ambiguously Gay Duo.”

Sedelmaier says that the exhibit developed “out of necessity – the necessity to find SOME way to share and make sense out of so much of the ‘stuff’ our studio has collected and preserved through the over three-and-a-half decades I’ve been involved with the animated film industry.”

The exhibit presents equipment, materials, and various applications of artwork used in the production process throughout the 20th century. Sedelmaier has been collecting these materials ever since he entered the industry in 1980, and he presents not just the equipment but also the stories behind the machines – who used them, how he found them, and what purpose they served in the production. “Every piece you see has a story behind it,” he says. “Whether it’s the person or studio that used it, or the productions it was used for, they all have a unique lineage.”

Below, we asked Sedelmaier to share with Cartoon Brew readers five of the pieces in the exhibition, and their importance to the classical animation process. It scratches the surface of what can be seen on display at the actual exhibit, but it makes quite clear that technical innovation has always essential to the production of motion picture animation.

The exhibit runs through April 29. Admission is between $3-5, and free for the school’s student, alumni, faculty, and staff. For more information visit Grohmann Museum website.

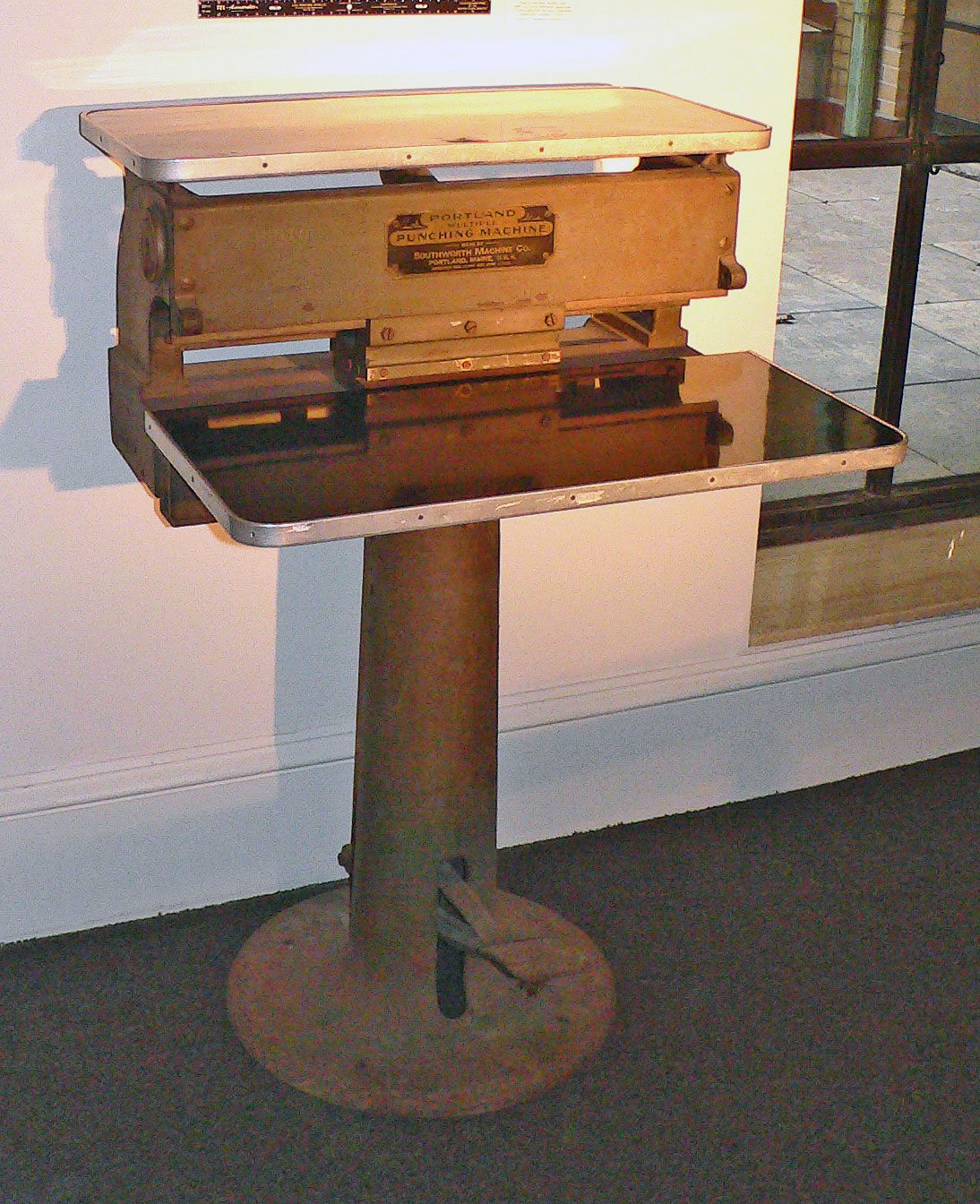

1. Bray Punch

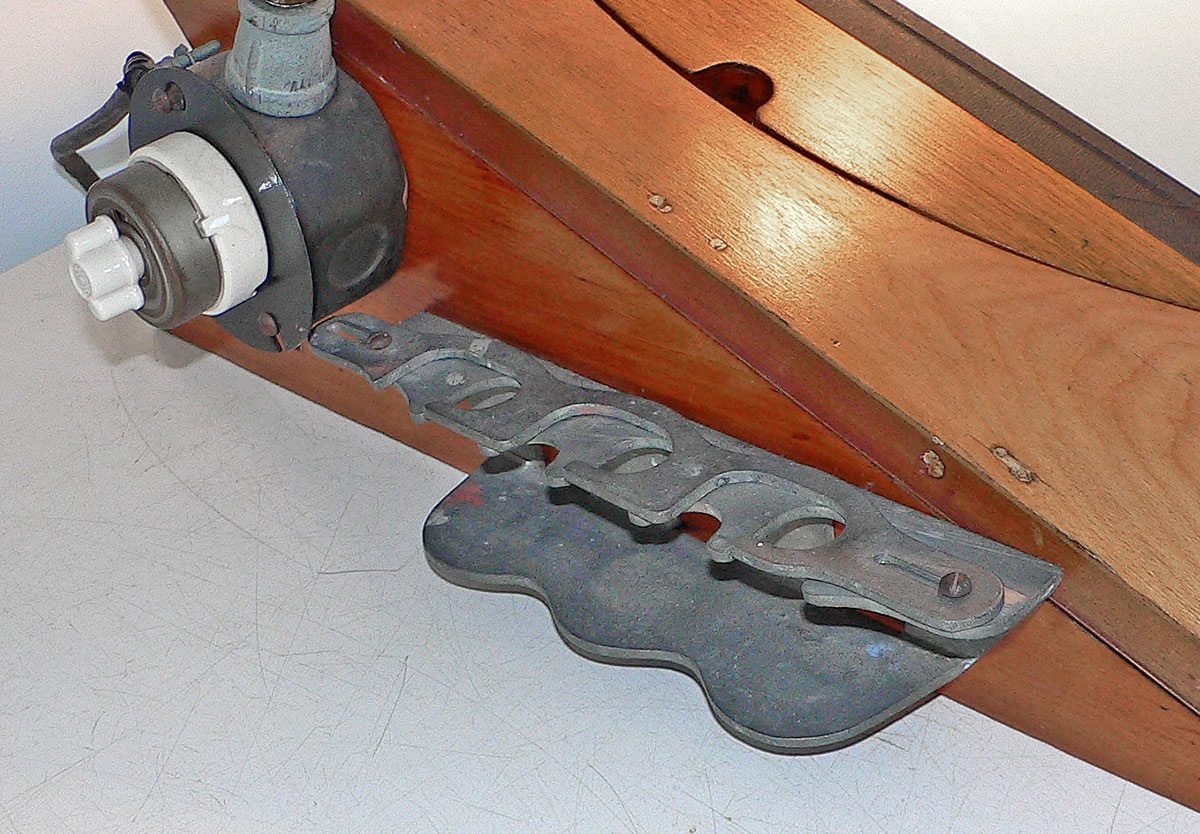

J.J. Sedelmaier: This cast-iron contraption was used to punch the registration holes in sheets of paper and acetate at a time when drawings were done on a lightbox and traced with ink and/or paint onto acetate “cels.” The registration holes corresponded to pegs (sometimes two round ones, sometimes two squared ones with a single round peg in the center) that all the artists and camera people used in production of the cartoons.

This particular machine dates from 1914 and had originally been a book-binding punch that had been modified to function for the animation production process. It was activated with a foot-pedal and would punch perhaps as many as five to seven sheets simultaneously. The waste paper/acetate would be automatically dispensed into a sliding wooden drawer located under the male/female blades.

I acquired this device from Penny Bray, legendary cartoonist/animator/producer John R. Bray’s granddaughter-in-law who worked at the Bray Studios until it closed in 1983 after almost 70 years in the film production business. She had a garage sale in Connecticut in the early 2000s and she gave it to me for free if I could figure out how to transport it from her premises. I verified its use within the Bray Studios during the 1970-80s with the help of former Bray employee, Monroe Oakley. He also explained that the faint lettering on the front of the punch saying “Audio”, was a remnant from its days as a punch used at the Audiocinema Studio (1929-1931), a precursor to Paul Terry’s Terrytoons studio in New Rochelle, NY.

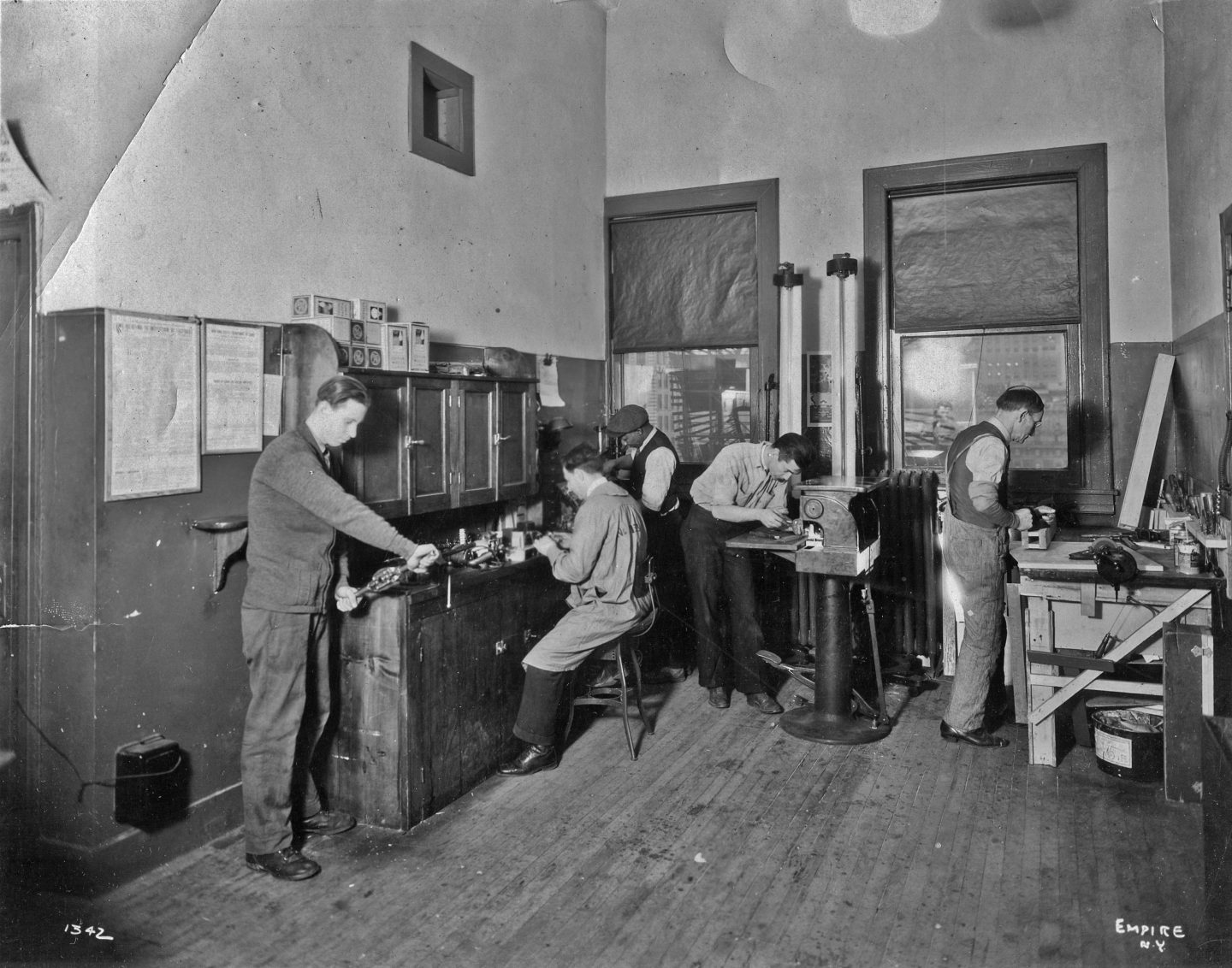

But wait – there’s more! I thought that I had traced this machine’s heritage fully until I received a cache of material in November 2017 from the family of Max/Dave/Joe/Lou Fleischer who now reside in Florida. Mixed in amongst several photographs was a shot from their workshop at their 1600 Broadway studio. It shows several workers busy at various tasks. A closer look shows a man in the center standing at the same punch described above. Because this device was a specially converted machine, I honestly can’t fathom there being two of these machines. I’m assuming that this photo is evidence of this punch having hopped between three New York studios. The chronology was probably: Inkwell Studios/Fleischer Studios (1910s-1920s), Audiocinema Studio (1930-1931), and then Bray Studio (1931-83). Needless to say, The “Bray Punch” is now “New York Studios Punch.”

Replaced By: Today, the registration of the drawings and assets is all a part of digital technology – it’s automatic.

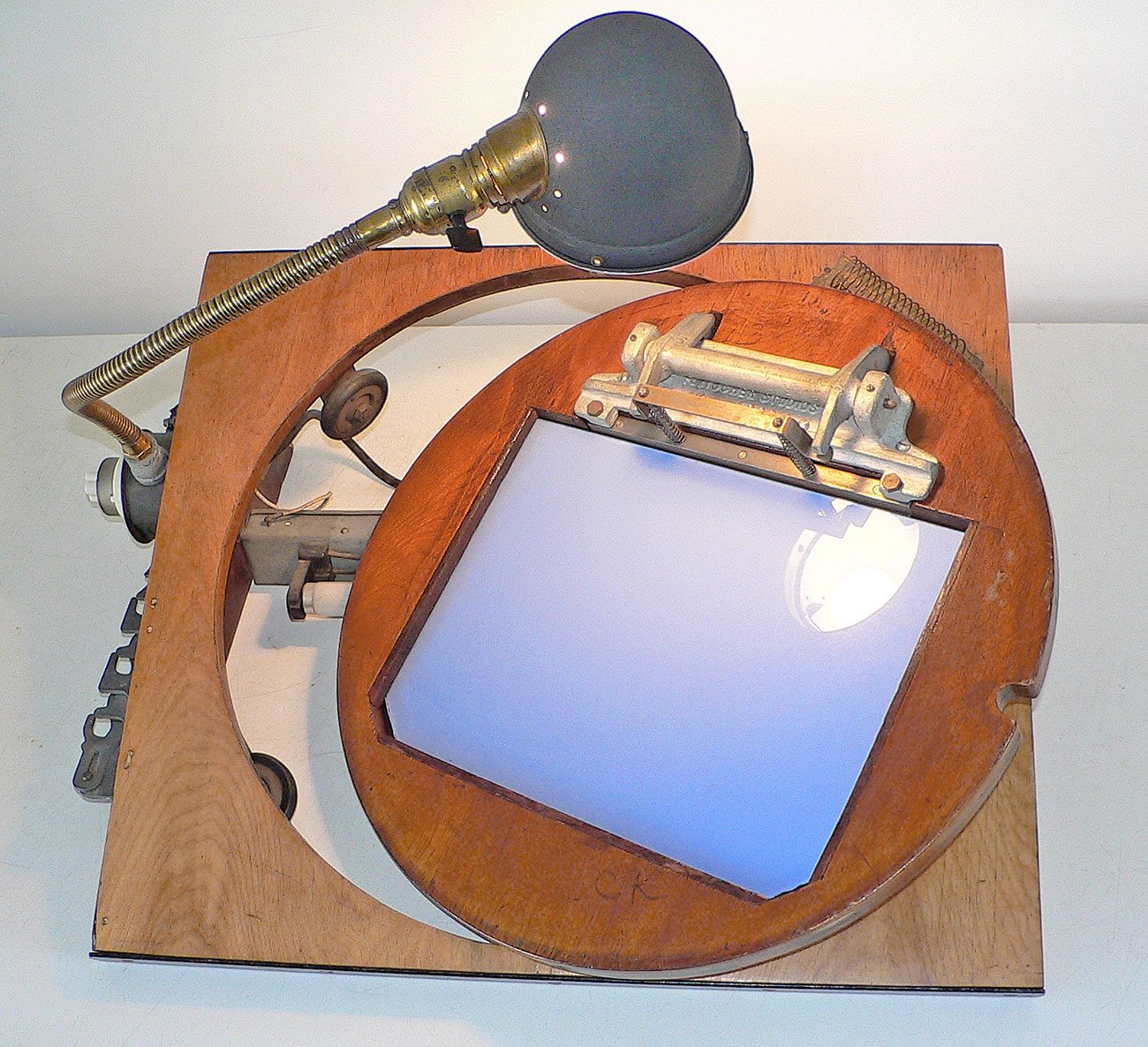

2. Animation drawing disc

J.J. Sedelmaier: Before animators and production artists worked exclusively in a digital domain and created their artwork on tablets like Cintiqs, production artists worked on animation discs and desks that were set over a light-source. This allowed for the artists to see through the drawings in order to plot and confirm the sequential action/movement of the animation. This process was used throughout most of the 20th century.

The various studios would devise variations in the design of their equipment to meet the specifics of their production needs, but the Fleischer Studio took this designing process to a new level. The fact that Max Fleischer and his brothers were technicians and inventors pushed their innovation to new heights.

By the mid-1930s, the Fleischer Studios in New York City, where Popeye and Betty Boop cartoons were made, had become one of the largest and most well known cartoon makers in the industry. One of the things that resulted from the studio’s growth was the necessity of more equipment for its employees, so they embarked on the design and manufacturing of new drawing disc lightbox “wedges” that could be placed on a flat surface.

The resulting disc set-up not only provided the artists with a revolving disc for drawing upon, but also an ingenious system that could remove a stack of animation drawings off of their pegs in an even manner so as to not stretch or rip the holes in the paper. This device was cast in aluminum and consisted of springs and levers attached to the underside of the disc itself.

The Fleischers also applied for a patent (added to the many they already had registered in Washington D.C.) for this invention, and the underside of the device is stamped “Patent Applied For Fleischer Studios 1938”. Regardless of the weight saved using aluminum as opposed to brass or steel, the disc was still quite heavy. In order to alleviate the struggle it would have taken to merely turn the disc during drawing, the Fleischers ordered a supply of ball-bearing roller skate wheels from the Chicago Roller Skate Company, and installed four spinning wheels under the disc to facilitate an effortless turning of the drawing surface.

They also created an “inkwell holder” that was attached to some of the wedges that could hold three bottles of ink, with a sliding clamp that grabbed the necks of the bottles to prevent spillage.

Go HERE for a comprehensive presentation of animation pegs and discs.

Replaced By: Wacom is probably the largest animation hardware provider today — though there are plenty of other tablet monitor manufacturers as well — and their Cintiq tablets come with software packages to meet just about any animation need.

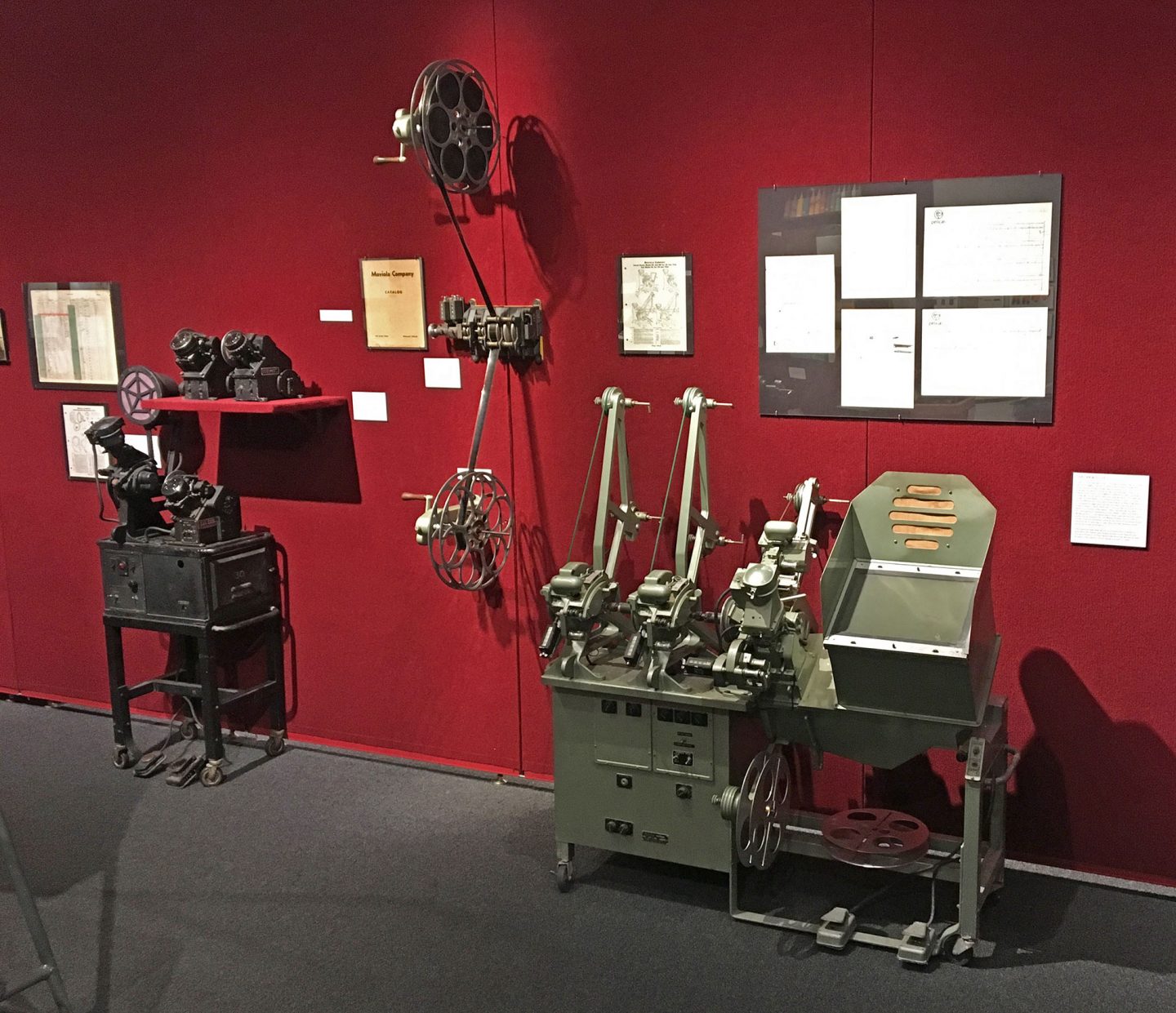

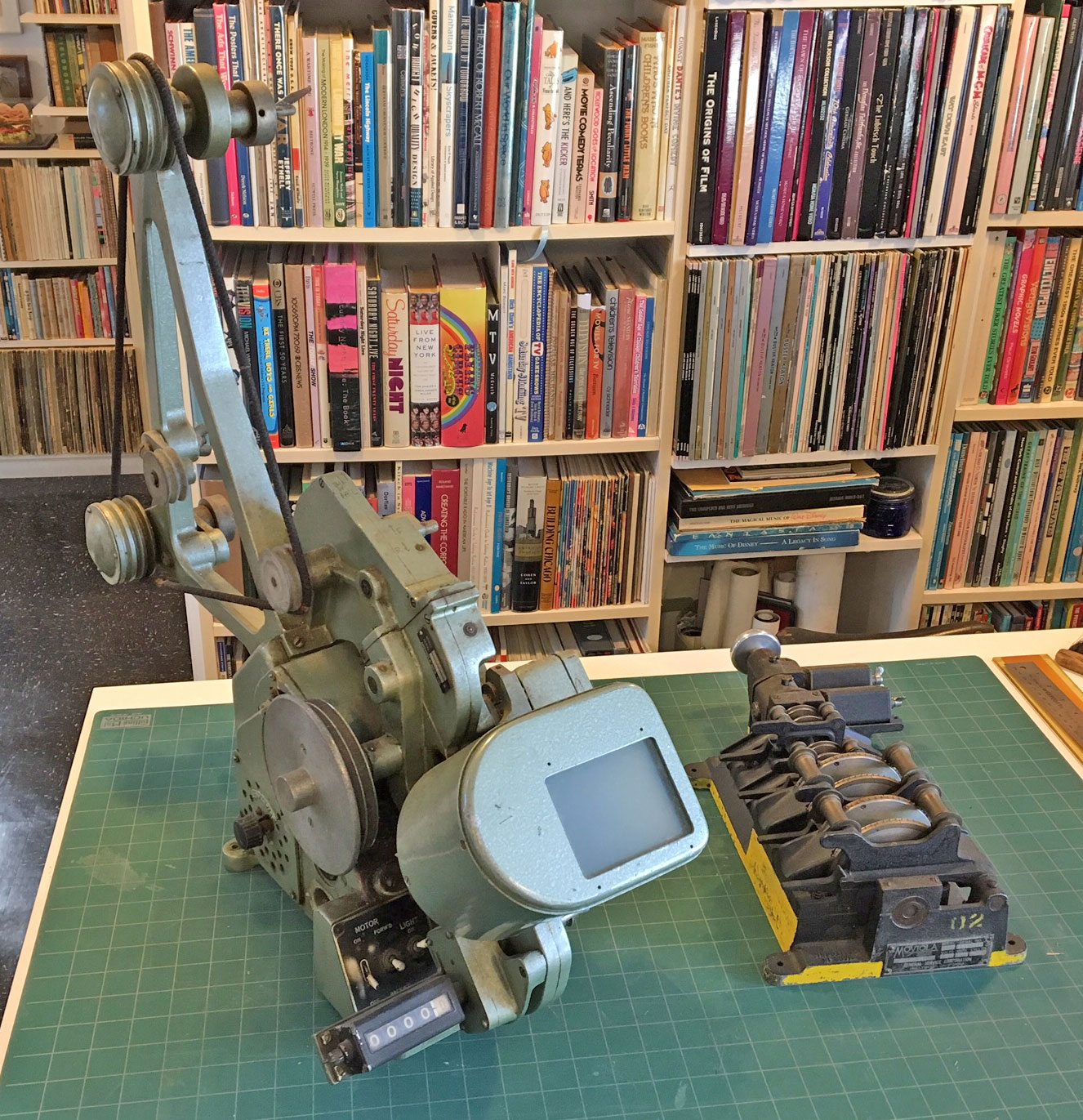

3. Moviola

J.J. Sedelmaier: The “Moviola” was first used in 1924 and was the mainstay of the motion picture editing process until digital technology absorbed “film” production a couple decades ago. There are five Moviolas of various types in the exhibit.

A Moviola was a type of projector used in the editing process. It allowed for the screening and synchronization of 16- or 35-mm motion picture film with audio (magnetic and/or optical tracks). They ranged from large machines on a wheeled chassis like the 1950s green “Preview” model (whose screen could also act as a surface for tracing live/animated motion picture footage for motion reference) to small, portable “Picture Modules” that could be placed on a desktop.

Replaced By: Today, the editing of film can be accomplished with a variety of software that deals with digitized footage and files. Adobe, Apple, and sometimes the animation software itself provides editing tools.

4. Planning Board

J.J. Sedelmaier: Towards the end of the animation production process came the “checking” stage. This important phase involved a checker or production coordinator basically putting the entire inventory of production art through the same process as the cameraperson would in the final stage. All of the art had to be checked for mistakes and the relationship of all the animation art, including character levels, backgrounds, etc., had to be checked, cleaned, and inventoried so there would be no mistakes or issues under the camera, when it would be too late to fix.

The checker could simply use an animation disc and lightbox to do this, or they could use a “planning board.” The planning poard that’s included in the exhibit is a one-of-a-kind item designed by journeyman animator Jack Zander (MGM’s Tom & Jerry, Pelican Films, Zander’s Animation Parlour) and made by camera master John Oxberry in the 1960s, when Zander had his own studio.

It provides the checker with every conceivable format for an animated film to be produced. It was designed to lay over a conventional animation desk, utilizing the light below. It’s made of aluminum with brass sliding pegbars. Oxberry owned Oxberry Camera Service in Carlstadt, NJ and was the acknowledged expert in animation cameras and equipment. He designed his own registration peg system called (wait for it…) “Oxberry.” Jack undoubtedly knew that there was no better person to approach to design and manufacture something like this.

Replaced By: The planning and checking process has been integrated into the various software that is used to produce animation nowadays. The “Final Camera” stage is no longer an ominous process because everything is revisable during the process.

5. Film case

J.J. Sedelmaier: From the beginning of the theatrical motion picture industry, there had to be a method of transporting and delivering the reels of film to the studios, editors, and movie theaters. This was also at a time before “safety film” and when the highly flammable and combustible nitrate film stock was in use. Here is a cardboard-lined, steel “Famous Players-Lasky Corporation/Paramount Pictures” film case dating from 1927-33.

Replaced By: Today, if film is still used in a theater, it will be transported in round metal cans, but if the film is a digital file, it can be uploaded/downloaded digitally.

.png)