Inside The Artist’s Studio: Luc Chamberland

Seth’s Dominion (2014), Luc Chamberland’s loving and mesmerizing portrait of the world of the acclaimed Canadian cartoonist, Seth (It’s a Good Life, If You Don’t Weaken, Palookaville), is a fascinating exploration of the artist’s complex world; one that is nostalgic, sad, and yet somehow hopeful and inspiring.

Skirting between live-action interviews and animated recreations of Seth’s work, Chamberland takes us inside the artist’s creative process (and astonishing productivity), while giving us hints of a man seemingly still struggling to make sense of a somewhat fractured childhood and a past that no longer is, and perhaps never was. Seth’s beautiful, detailed art seems to be his escape, his sanctuary. It’s as though he didn’t like the world he was given so he just made up his own.

But Seth’s Dominion isn’t only about Seth.

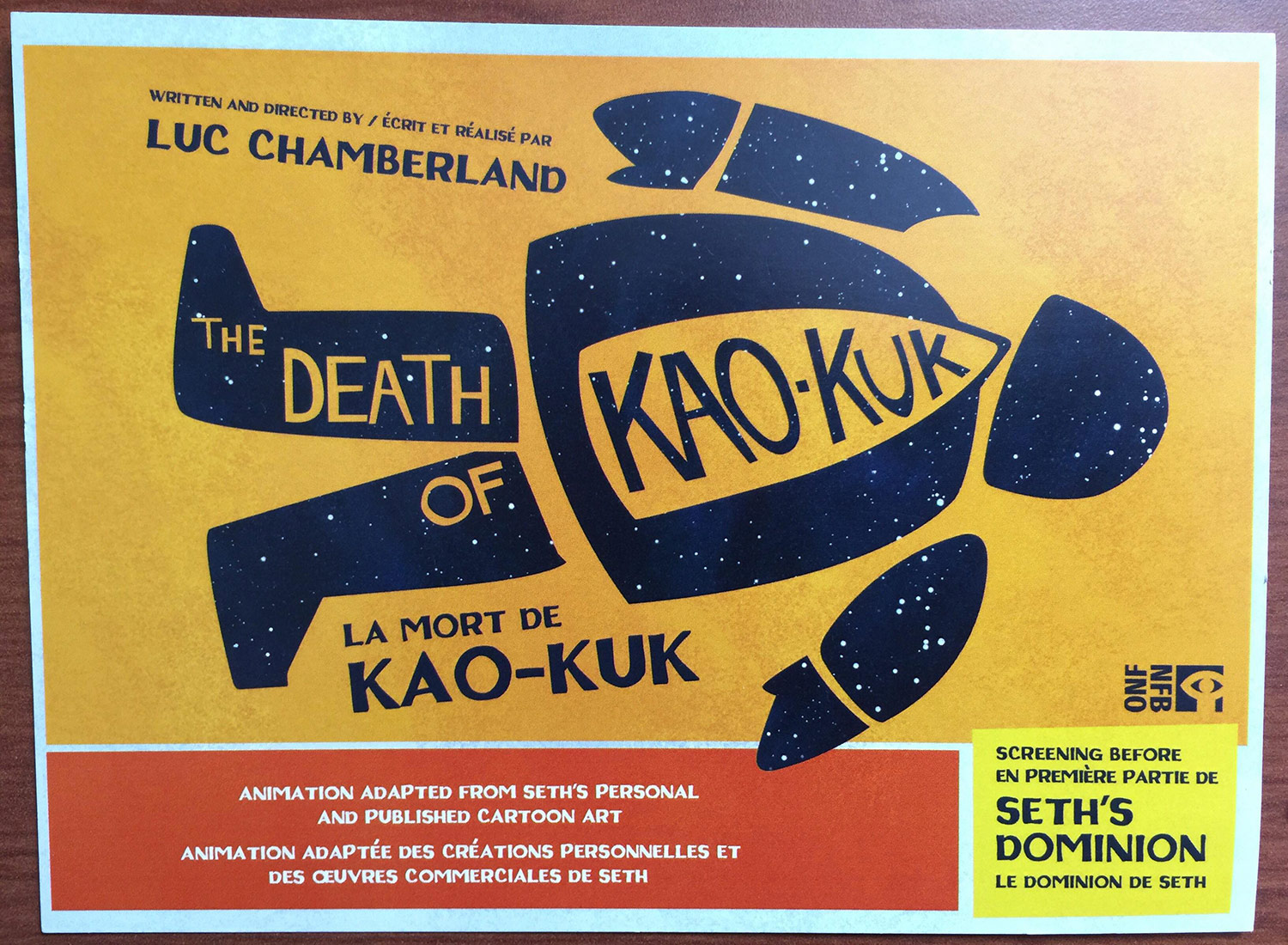

In his introduction to the beautifully designed book and dvd edition of Seth’s Dominion (which includes a short making-of along with two shorts based on Seth’s stories, The Death of Kao-Kuk, The Great Machine), Seth serves up some interesting insight: “I saw the film several times. While watching it…something occurred to me. In some way… the film was more about Luc… than it was about me.”

“It’s true that this is my vision of him,” says Chamberland during our recent chat in Montreal. “A different person would have done a different film. It’s a film about my sensitivities about life. I see the angst in Seth’s work. I related to his characters. I wanted to talk about life and how we should take things and find sweetness. I saw it underlined in Seth’s work. I took advantage of his work to talk about things that interested me.”

And when you learn that Chamberland spent seven years working on Seth’s Dominion (almost like a hobby, he says), you begin to understand what Seth means. “I was teaching part time in the mornings,” he says. “and then after I would head to the NFB [National Film Board of Canada] and work in the afternoon until early evening.”

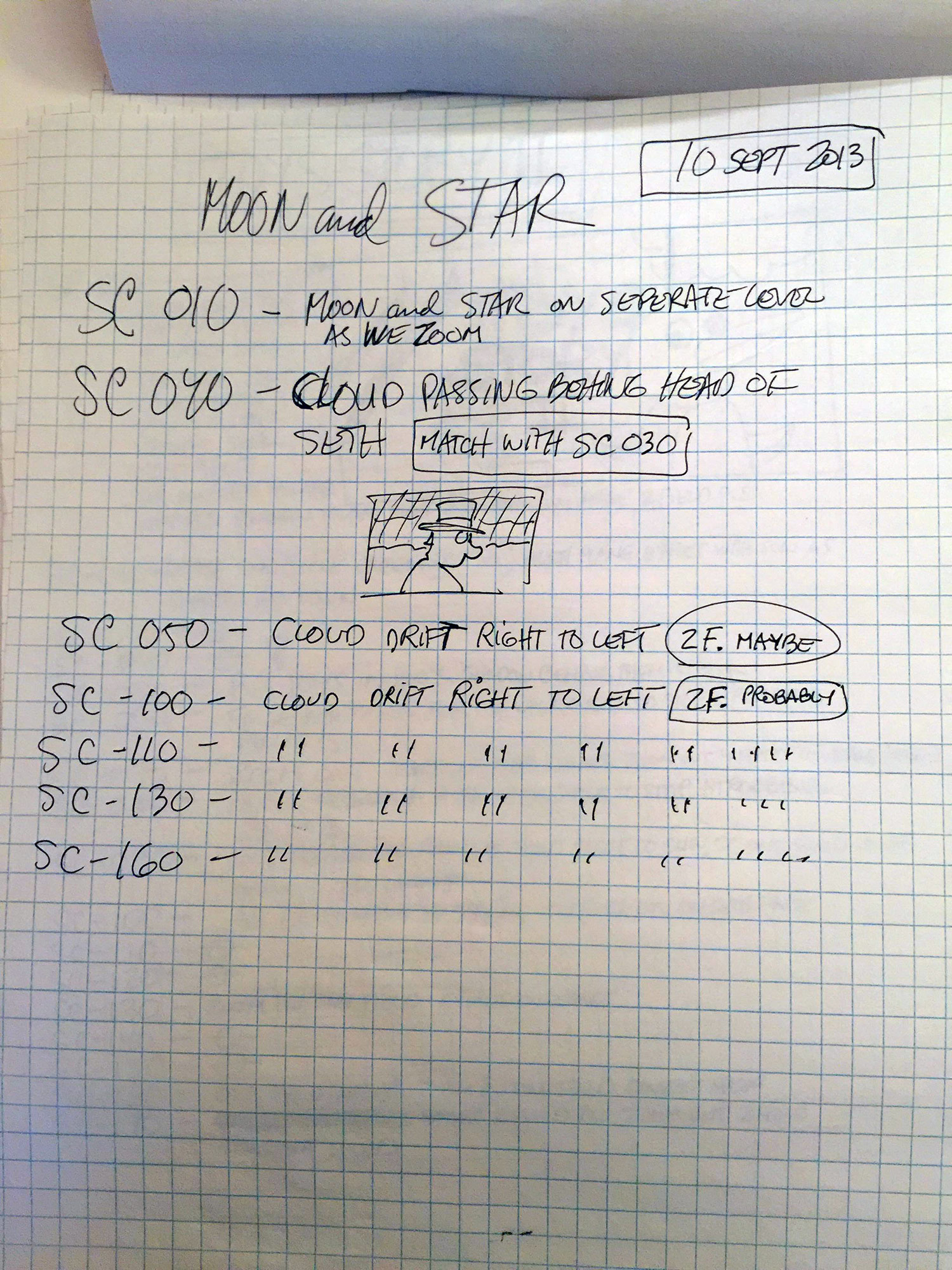

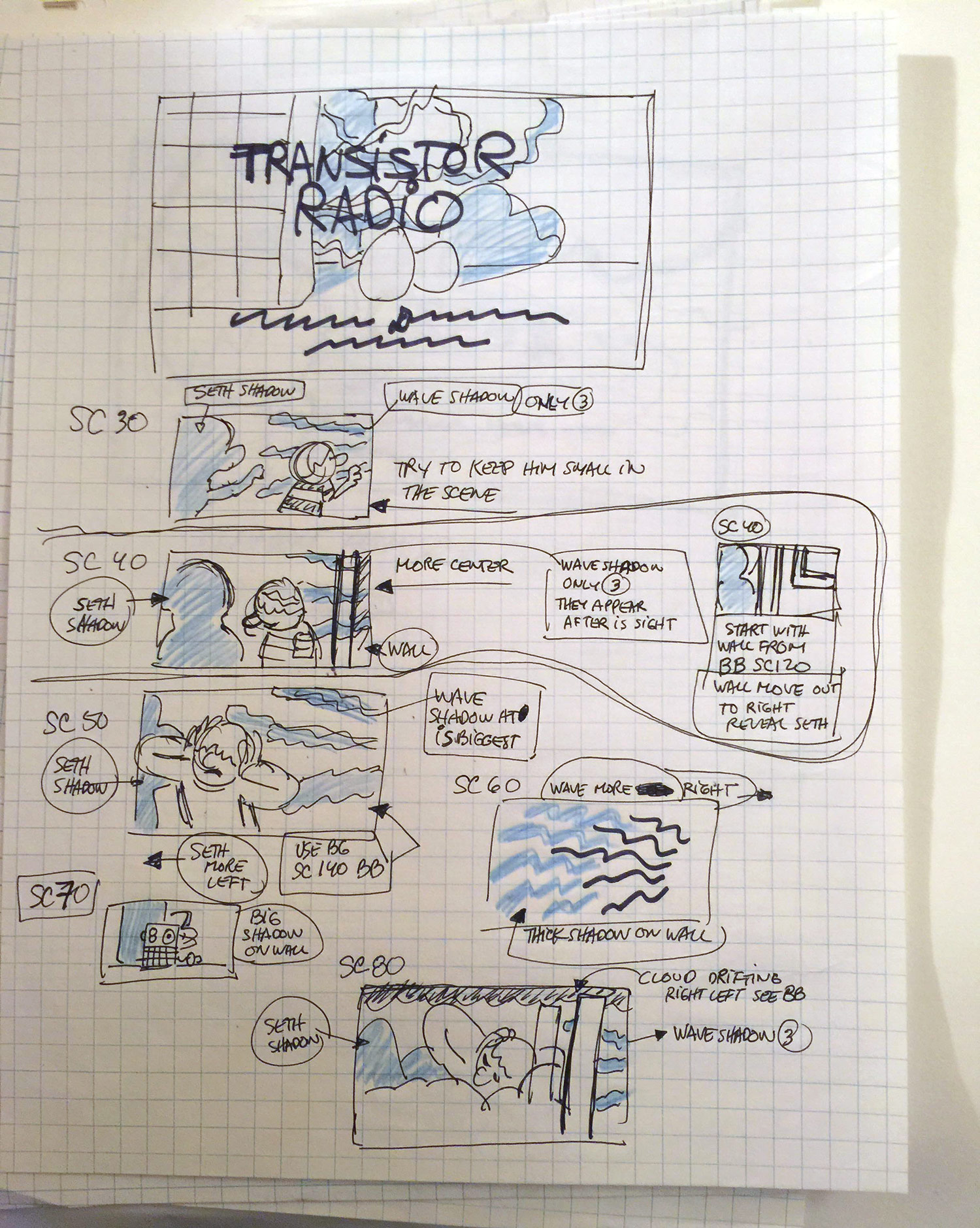

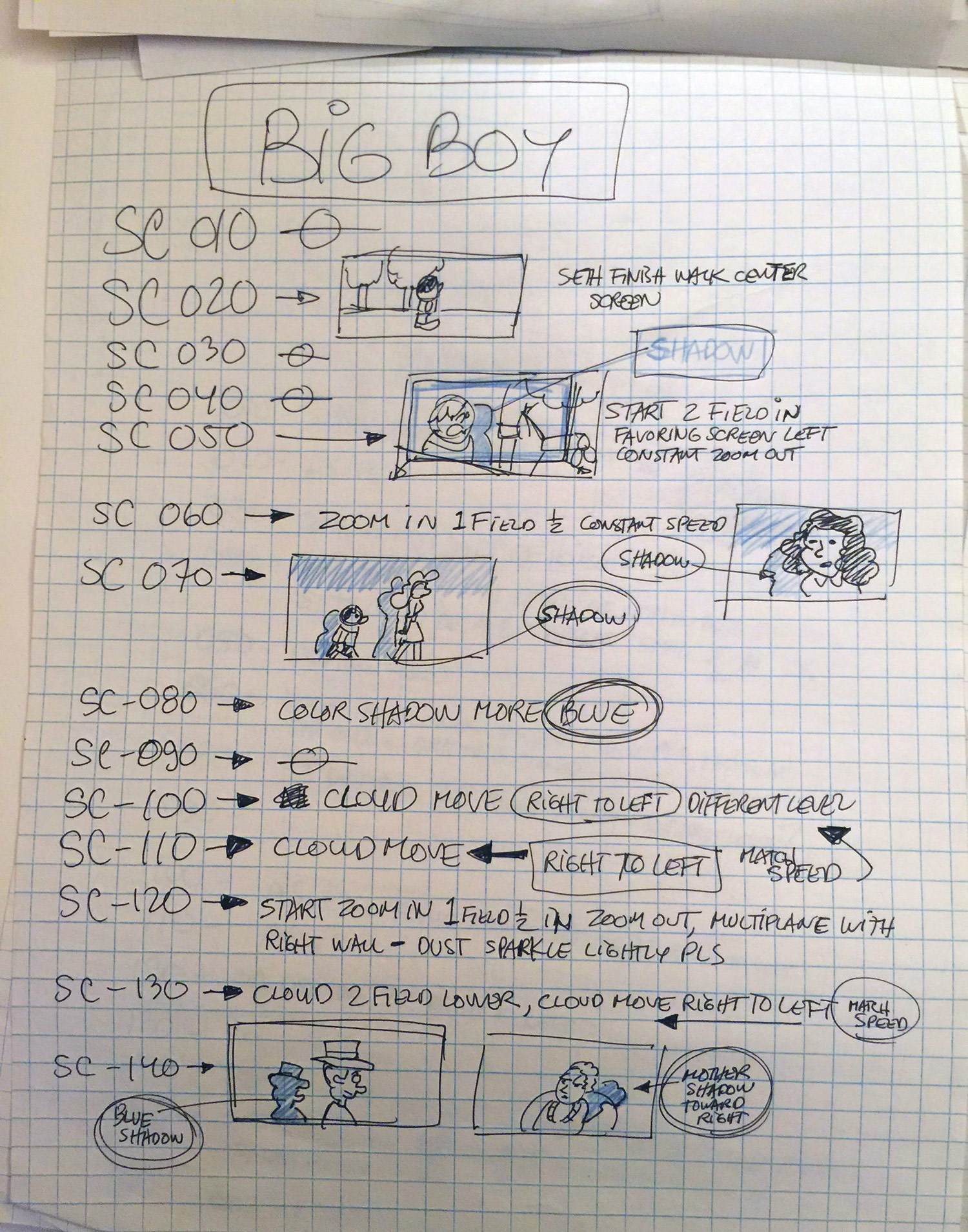

During those years, Chamberland also worked on a tv series (Wild Kratts), made an animated documentary short (Saga City, 2011) along with an assortment of commissioned works. “Everything I was doing was for Seth,” adds Chamberland. “A lot of the money I made for those projects went into the film. Usually I had to balance at least three things at once. This is why I use notebooks so that I organize these different projects. This doesn’t include travelling to Guelph, Ontario, Toronto, and New York to conduct interviews for the film.”

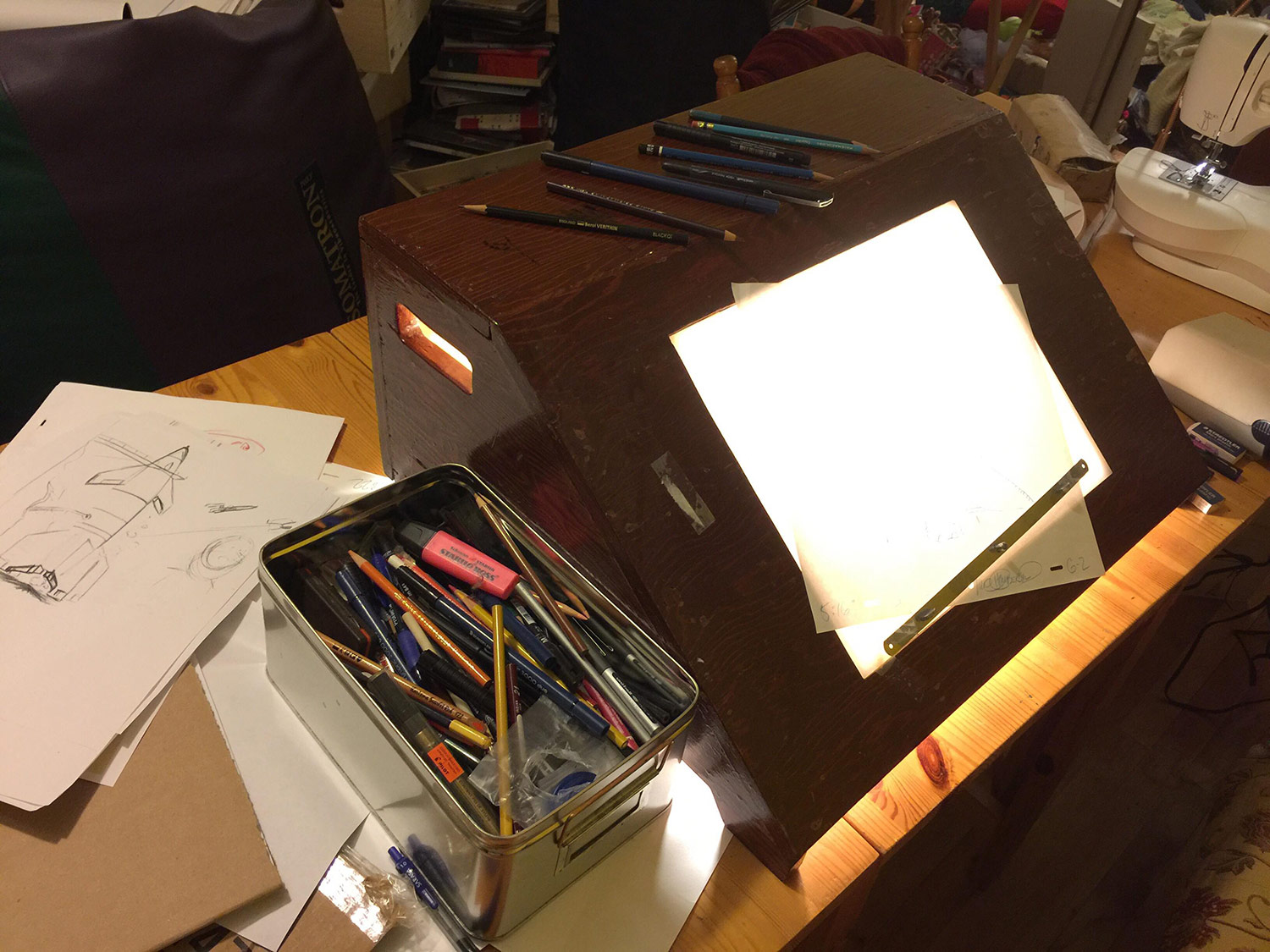

While many viewers are convinced that the animation segments in Seth’s Dominion were hand drawn, in fact only three scenes were done on paper. The rest was made on a computer. “I would prefer to do it on paper,” says Chamberland, “but budgets are so small that it’s just impossible now. I like to have something tactile, having the artifact in your hand, getting your fingers dirty.” (Chamberland recently got to switch to paper when he was chosen to recreate missing Winsor McCay drawings of the seminal Gertie the Dinosaur, as part of a restoration project undertaken by Cinémathèque québécoise, National Film Board of Canada, and University of Notre Dame.)

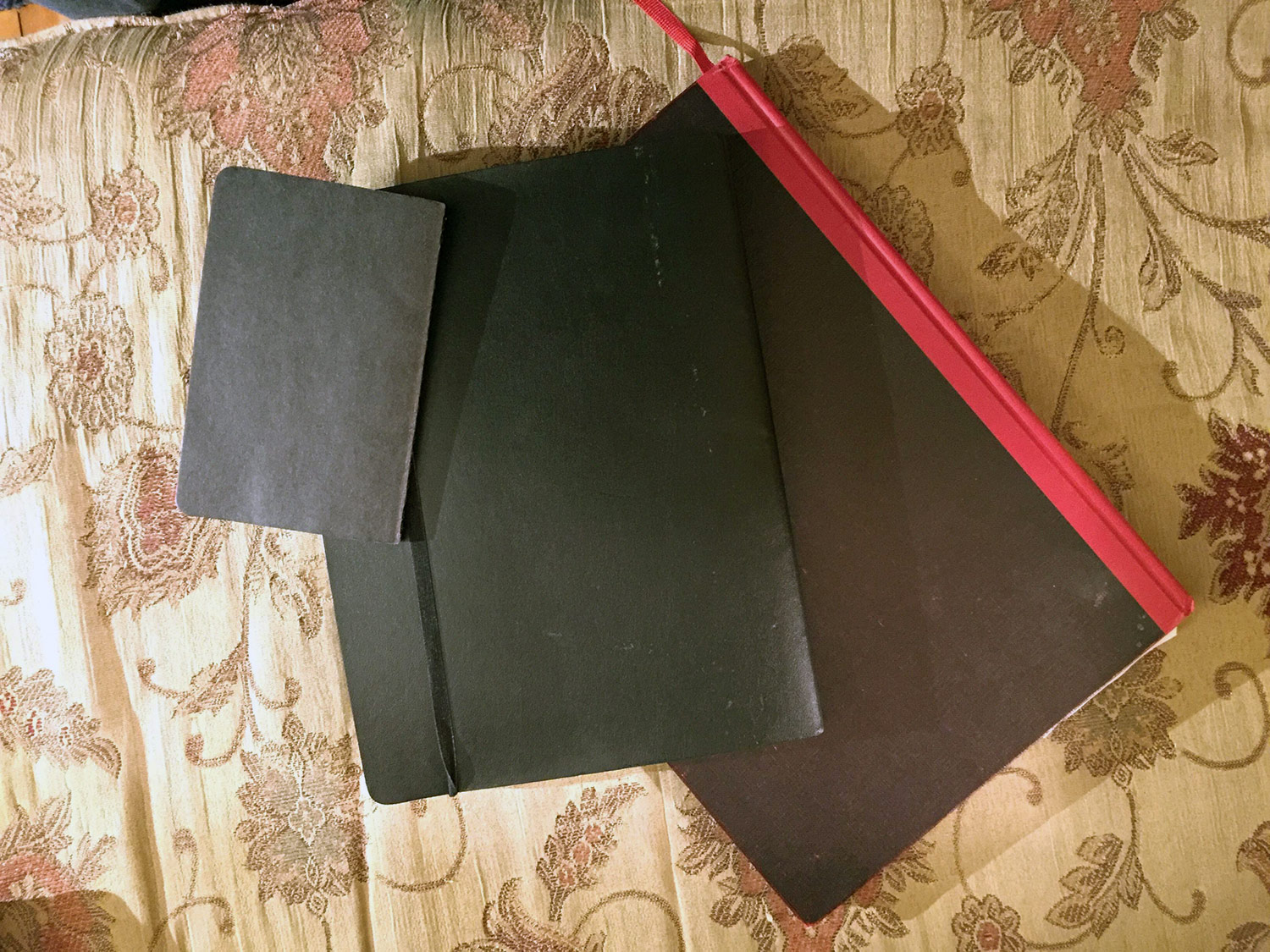

In fact, it’s rare to run into Chamberland without pens, pencils, and notebooks alongside. “Wherever I travel I always have pens and pencils in every pocket, and small books with square layouts help me make frames for scenes compositions, a small [book] in my jacket pocket, a medium in my bag, and a big one for home so I’m always ready to jot down the many ideas that attack my head.”

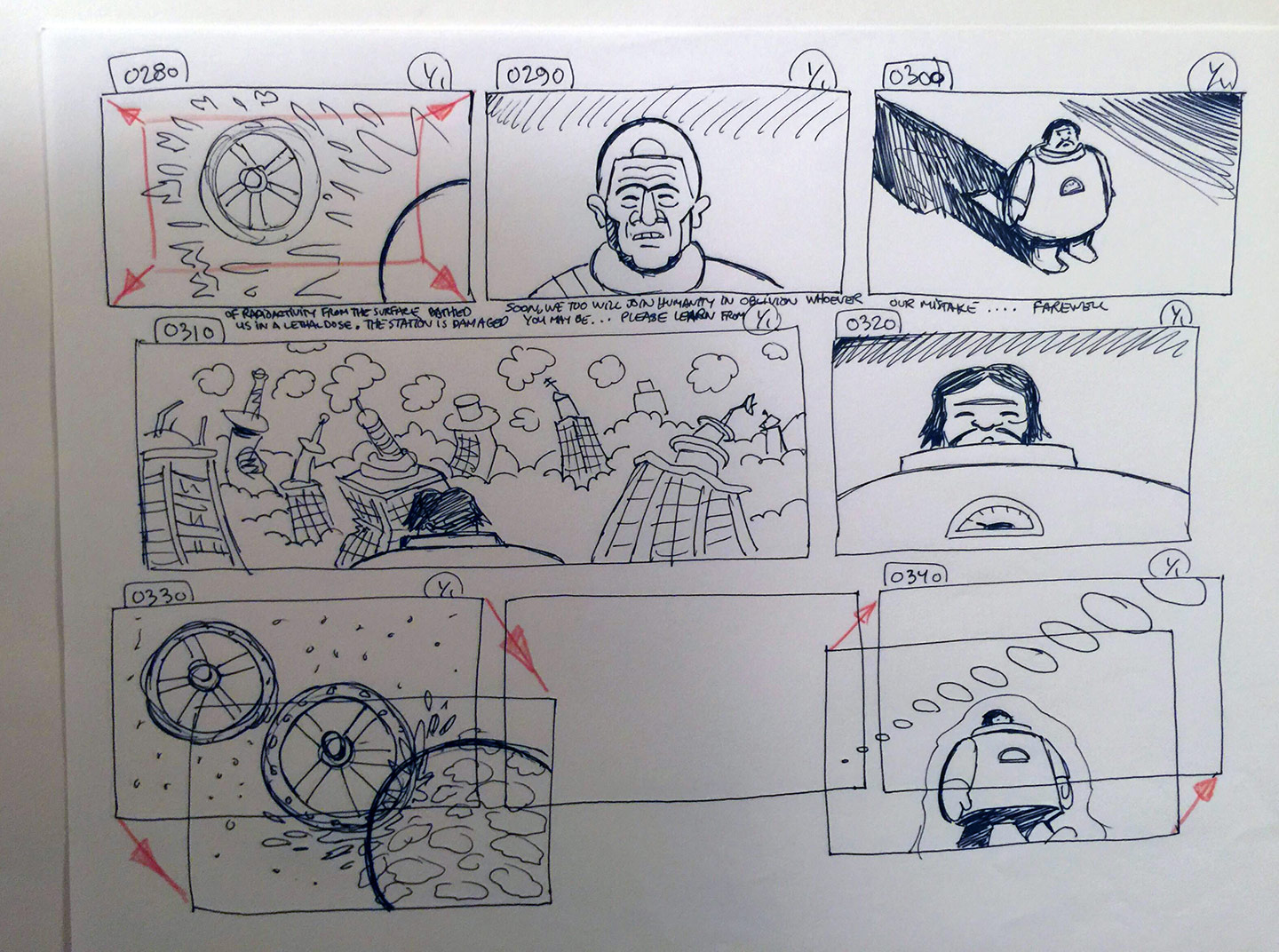

“It’s very neat that I draw on the Cintiq tablet, but it’s weird for me because it feels like [the artwork] doesn’t exist, though I know that it does exist as a film. I really worked hard though to make people believe it was all done on paper. We scanned old paper to get textures, and to get a brush that looked like it was inked by hand. I did a lot preparation on thumbnails and I did nearly all layout on paper, and then I scanned them and put them on the Toon Boom Animate software.

Although he has worked on many major studio productions and commissioned projects throughout his career, Chamberland admits he found the task of adapting Seth’s distinct retro style cartoons to animation stressful. “I was very scared when it was time to show him the first animation. I worried that he wouldn’t like it.”

Chamberland found the pacing a couple of ways. First, by observing Seth’s movements during their interviews: “I saw,” adds Chamberland, “a strong, quiet tranquility inside of him that I wanted to emulate.” Secondly, he asked Seth to record the narration for every animation short used in the film. “That’s when I found the rhythm. Music is very important for me and I didn’t have any music… so his voice became the music in a sense.”

Chamberland didn’t need to worry. “The second that Seth saw the animation he was smiling and happy. He was almost honored that it was well done. And like that, all my angst vanished.”

From the beginning, Chamberland had carte blanche with the film. “Seth was clear that he wanted me to have complete freedom. He doesn’t like being told what to do and wanted the same for me.” The only people who did take Chamberland to task were NFB folks. He originally envisioned a film that was broken into small parts. “I had an elaborate synopsis but I was told that it was too confusing and needed to be more linear. The situation reminded me of Oliver Stone’s JFK. He constructed the film in the same way, but was told to make it more linear. So he rewrote it like that, but in the end, he cut it the way he wanted. So when I was asked to make it more linear, I smiled and agreed, and then I broke it back apart when I made the final cut and everyone said it made sense.”

I wondered what were some of the biggest challenges Chamberland faced – other than keeping focused for seven years – when he approached a subject who mostly just sits in his basement and draws. “When I initially had the idea for the film, I wondered who’s going to see this and how can I make it interesting? I’m a bit of a film buff and so I watched a lot of films about cartoonists. The two that helped me a lot were Crumb and American Splendor. I didn’t want to do a film about a guy talking and drawing. I wanted to do a film about life and the subject matter in Seth’s books.”

While the bulk of Seth’s work carries an underlying sense of loss, alienation, and anxiety, Chamberland uncovers the hope and joy within that deceptively gloomy vision. He does this not just through his re-interpretation of Seth’s world, but through the neverending flow of positive energy and excitement he brings to the film. You can feel Chamberland’s love and admiration dripping through every frame of the film, not in some salivating fan boy manner, but with a profound respect and empathy. Both artists remind us that this is all so fleeting and that we have to put aside our fears and unhappiness, that we can take control of who we are and how we choose to live.

You’d be hard pressed to find many artists these days who would be so devoted to a project for a couple of years, let alone seven, but Chamberland never lost sight of where he was going. “I was very focused. I look like a person who is all over the place. I have pens in my pockets. Notebook in my bag. Notebook in my pockets. Notebooks everywhere…. there’s too much stuff happening in the head so I write it and write it and get it out. The more I do that, the more it seems to control it. I put it on paper there so I don’t have to think about it. It’s there.”

In this age, or, hell, any age, how can someone be this consistently optimistic and happy (let’s not forget Chamberland’s loud, boisterous laugh that is recognizable to anyone who has been in a room or cinema with him)?

“I look like a happy go lucky person,” he admits to the surprise of no one. “I impose happiness daily and hourly. I find that extremely important because the angst I have inside is killing me. So I am really disciplined about imposing fun in every endeavor. I want everything to be a great experience and life is short. My daughter is severely handicapped. They told us she wouldn’t live past four. We had a little cry, say twenty minutes. Then we said, let’s make sure she’s going to have fun. We made every day happy. Now she’s 18 and she’s still happy and keeps having fun. A state of mind helps everything you do.”

.png)