Borivoj Dovniković-Bordo, Major Filmmaker From Zagreb Film, Dies At 91

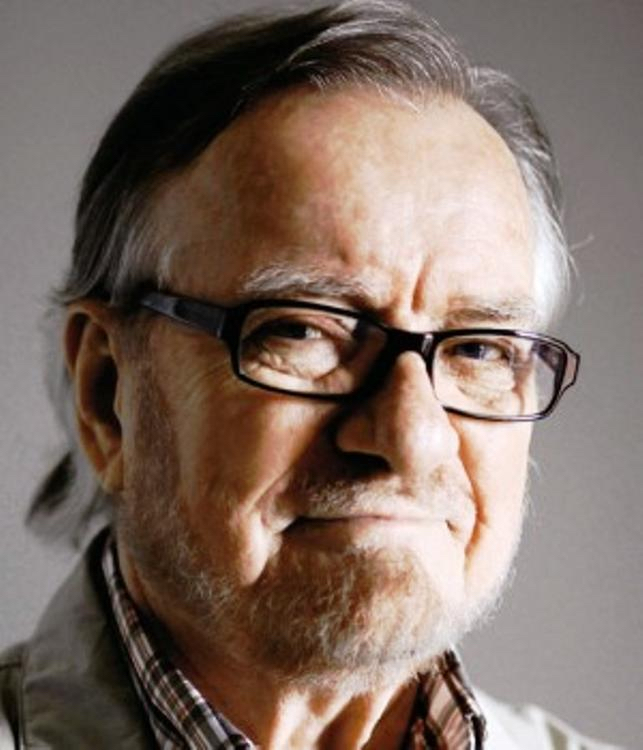

Borivoj Dovniković-Bordo, one of the most respected and influential filmmakers to emerge from the famous Zagreb school of animation, passed away on February 8 at the age of 91.

Bordo, as he was known to most, was born on December 12, 1930 in Osijek, Croatia (then Yugoslavia). Aged around 19, he moved to Zagreb to study at the Academy of Fine Arts. A year later, he joined the satirical weekly Kerempuh as one of the caricaturists. The magazine was popular, and the editor, Fadil Hadžić, was inspired to put some of those profits into a satirical animation short.

The result was The Big Meeting (1951), directed by Norbert Neugebauer, and animated and designed by his brother Walter. Among the many animation assistants was Bordo. That same year, Hadžić founded Duga Film. Bordo, along with future Zagreb Film animators Zlatko Grgić, Vlado Kristl, and Dušan Vukotić, joined the effort. He worked on five films before the studio folded in 1952, after the Croatian government diverted funding to education and healthcare.

A few years after the demise of Duga, Zagreb Film emerged. Influenced by UPA and the National Film Board of Canada among others, the animation studio would become among the most influential around the globe. Zagreb Film was noted for its unique graphic styles, limited animation, and exploration of themes like war, society, and the very problem of being a human in an often chaotic, nonsensical world.

Bordo made his directorial debut in 1961 with The Doll, but it was Without Title (1964; watch a clip below) that started to bring attention to his work. This satire of bureaucracy, about a man whose efforts to be in a film are continually blocked by the opening and ending credits, won an award at Oberhausen.

From the start, Bordo’s work is preoccupied with regular guys making their way in a rather surreal and frequently interfering world. Each film starts with a gag and then riffs on it. Bordo’s films are also noted for their satirical punch, and minimal use of dialogue and design (occasionally mixed with collage).

Ceremony (1965) is a dark satire in which a group of guys pose for a picture during a ceremony that turns out to be a firing-squad execution. In Curiosity (1966; watch below), a man sits on a park bench with a mysterious paper bag. A parade of people (workers, school kids, cyclists, cruise-ship occupants) become curious to the point of intrusiveness, desperate to find out what it is in this bag.

In Krek (1968), winner of the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival, we follow a man who joins the army and brings his pet frog along. To the annoyance of his commanding officer, the frog continually distracts the man from his duties by taking him into a world of consumerist fantasy. The Flower Lovers (1970) is about a community that becomes fixated on exploding flowers. In Second Class Passenger (1974), a man encounters all sorts of oddballs (dogs, aliens, cowboys, astronauts, soccer players) during a train ride.

One Day of Life (1982) is a simple, compassionate portrait of a factory worker who briefly interrupts his dreary, repetitive existence by getting hammered at a local pub with an old friend. Exciting Love Story (1989; watch below) veers a bit away, formally at least, from his previous films. The screen is divided into eight frames and a man travels within each frame in search of his love, Gloria.

Midhat “Ajan” Ajanović, an animation scholar, teacher, and author, says that Bordo’s stories “always revolved around a goodhearted, affectionate, and naïve ‘little man’ who would find himself in trouble because of something totally unnatural and illogical, or due to human wickedness. Drawn figures proved to be perfect ‘actors,’ which transferred with great precision the author’s vision of an ordinary little man and his ‘struggle to live an ordinary life.’”

Echoing the stubborn, determined traits of Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin, Bordo’s characters are not pushovers. “After having undergone molestation in the first part of the film,” says Ajanović, “the character experiences a catharsis and transforms into a real fighter who refuses to be terrorized any longer. His ordinary men become totally extraordinary.”

Ajanović continues: “As far as figure design and drawing technique were concerned, Bordo, like Grgić and fellow Zagreb artist Nedeljko Dragić, was strongly influenced by Saul Steinberg’s purity and simplicity. Bordo was somewhat older than his colleagues, so his drawing style retained plasticity, volume, and a softness of line, placing his graphics halfway between Disney and Steinberg. As an animator, he was relaxed. His drawings were copied from the paper onto the cel with an unequally thick line that constantly pulsated on the screen, creating a lively and irresistible film image.”

Beyond his films, Bordo played an instrumental role in the founding of Animafest Zagreb, now one of the world’s best-known animated festivals, in 1972. He not only co-created the festival’s logo and first signal film but was also president of the programming committee in the early 1980s. From 1985 to 1991, he served as the festival director.

Margit “Buba” Antauer, who was the festival’s managing director from 1992 to 2006, recalls, “I met Bordo almost 50 years ago, during my first Animafest engagement. He was one of the founders and leading people of that special event that penetrated my blood and is still filling my heart with special energy. Bordo immediately had my respect and admiration.”

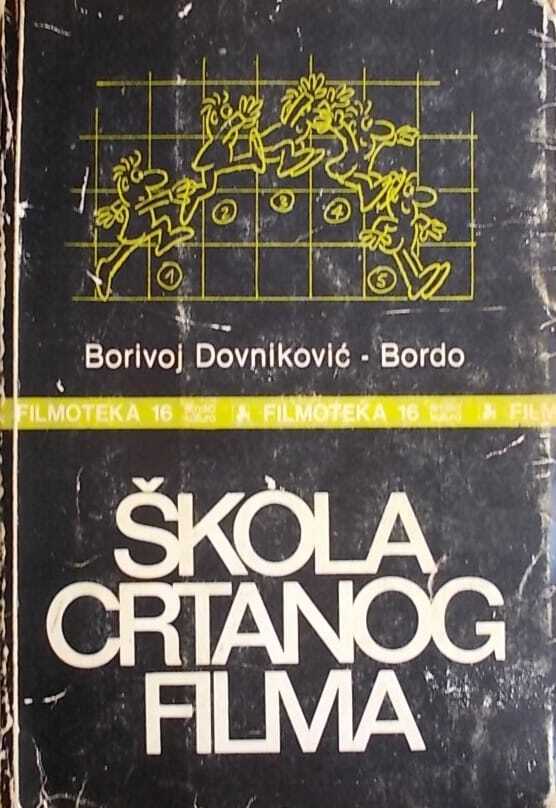

Many people were influenced by his animation book Škola crtanog filma (School of Animated Film, 1983), including animator and current Animafest artistic director Daniel Šuljić. “When I started as an animation student in Vienna, I did a lot of exercises based on his instructions from that book, and I know that other people did the same,” Šuljić said in a statement. “He taught us how to walk, just as the name of one of his best films, Learning to Walk, says. Bordo left us his films, simple, based on gags (as Ronald Holloway stated in his book Z is for Zagreb), but always deeply human, in the love of a ‘small’ man.”

Andrijana Ružić, an animation historian and author, concurs: “From that book, I have finally understood the meaning of a secret ingredient in an animated film — the famous timing. Bordo himself was a master of timing, and it is evident in his witty and sour shorts that he treated the everyday troubles of an ordinary man. His film are never consolatory, but what can console us really, in the end? Very few animators knew how to create the right timing of an ordinary man’s life like Bordo did.”

Antauer fondly recalls sharing some time with Bordo at the Animator’s Picnic at Animafest’s 2021 edition: “By chance, I could hear the words he was imparting to young student animators who gathered around him, knowing that they were lucky to meet a true animation legend. He told them, ‘Almost my whole life I not only dreamed, but I deeply believed that if we really try hard, animation will help us to reach the stars!’ And you did it, dear friend. You did it, and now you are one of them! And you will shine forever! Bordo — our superstar!”

Image at top: “Krek”

.png)