Leo Sullivan, Co-Founder Of Hollywood’s First Black-Owned Animation Studio, Dies At 82

Leo Dan Sullivan, the trailblazing Black animation artist who worked as both an animator and producer over a six-decade career, has died. He was 82.

Sullivan passed away in Los Angeles on March 25 of heart failure, his wife Ethelyn told The Hollywood Reporter.

A native of Lockhart, Texas, Sullivan’s family moved to L.A. in 1952. His father was in the military, meaning that the family moved frequently. He began his career running errands for Bob Clampett’s Snowball Productions in the early ’60s before becoming a cel washer on the producer’s Beany and Cecil series.

Sullivan once recalled discovering an early affinity for animation as a child, although the mechanics of how animation worked eluded him for some time:

I would go to the movies and see all these cartoons and I thought it was little people running around in costumes doing it. Then I started doing some research when I was in high school and I said “Hey, this is fantastic.”

Clampett promoted Sullivan to an inbetweener on the Beany and Cecil series, which marked the beginning of his career as an industry artist. Over the years, Sullivan worked for all of the major studios of the era including Hanna-Barbera, Filmation, DePatie-Freleng Enterprises, DiC Entertainment, and Marvel Productions. He contributed as an animator, layout artist, and sheet timer to countless animated shows including The Flintstones, Scooby-Doo, Mighty Mouse, Fat Albert, Super Friends, The Transformers, My Little Pony, Tiny Toon Adventures, and Animaniacs.

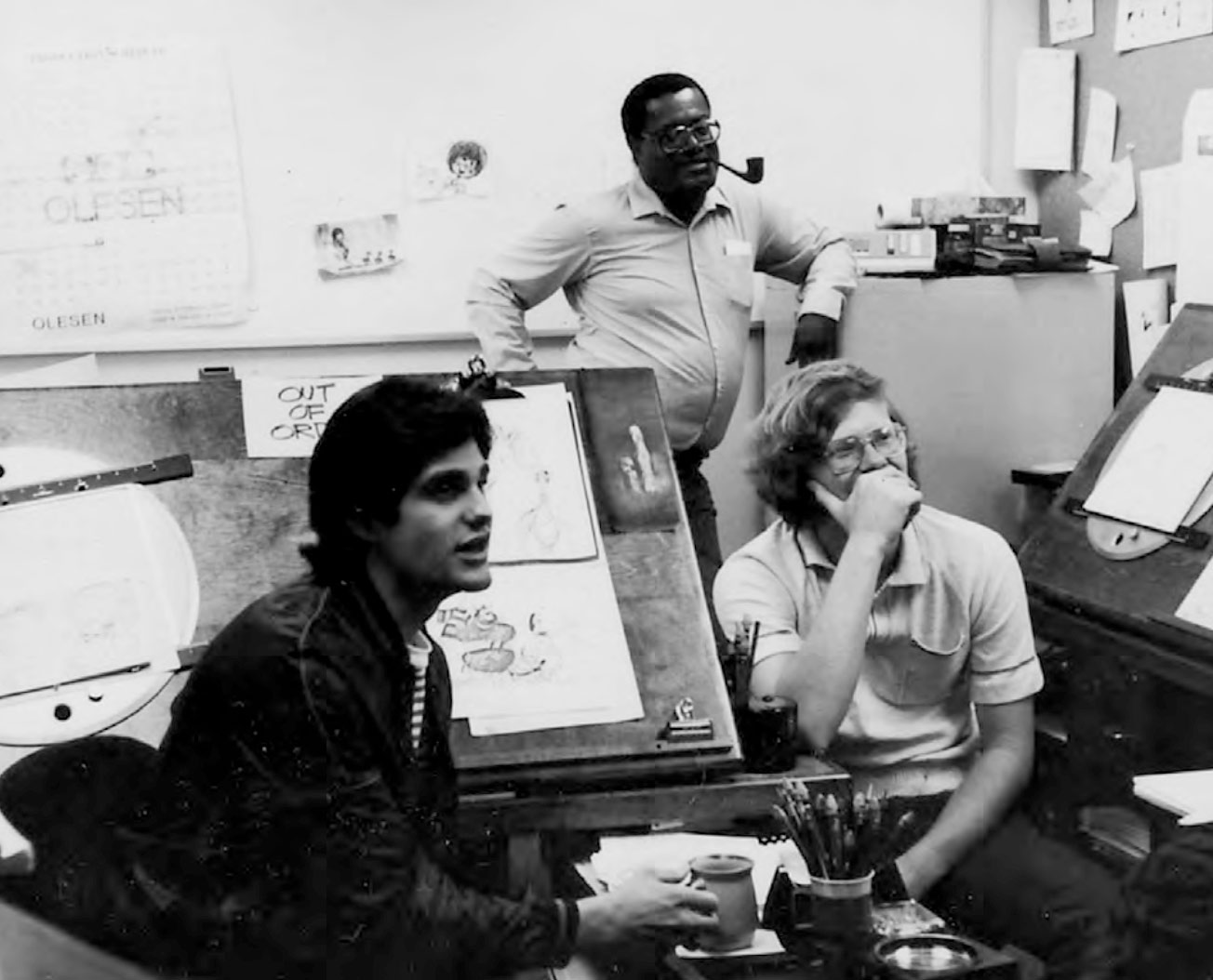

Sullivan also worked on the producing and management side of the business. Most notably, he co-founded Vignette Films in 1966, along with Floyd Norman, Richard Allen, and Norm Edelen. As the first Black-owned animation production company, Vignette produced educational films about Black historical figures like George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington. They also worked on various Hollywood tv productions throughout the 1960s, including the primetime tv special Hey, Hey, Hey, It’s Fat Albert (1969), the Soul Train series opening, and writing on sketch comedy series like Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In and Turn On.

“It was Leo Sullivan’s confidence that took us to the next level,” Norman wrote in his memoir Animated Life. “It was also during this time that I learned that my partner Leo was an excellent movie producer. Actually, it would not be exaggerating to say he’s better than most. During this time, it was highly unlikely that a black man would ever be given such a position in a major studio.”

In the 1970s, Sullivan ran the animation department at the L.A. commerical studio Spungbuggy Works. Throughout his career, he jumped between mainstream studio work and producing work through his own company. Sullivan did commercial work for ad agencies in the Caribbean, managed several animation studios in Asia, published a video game that honored the heroic Tuskegee Airmen, and developed and animated a character (named Walt) for the California Science Center.

In 2016, Sullivan and Norman reteamed to launch Afrokids.com, a label dedicated to empowering families and building children’s self-esteem and cultural heritage through educational and entertainment media.

Late last year, Sullivan appeared on the Reelblack Podcast to talk about the work he and the Afrokids team do in the kids and family space. The impetus for launching the company, he explained, goes all the way back to his early career when he saw characters from underrepresented communities being marginalized in animation, a problem he says persists today:

I realized that Black characters, different ethnicities, were marginalized. Sometimes marginalization comes in subtle ways. And I said, “Somebody needs to change that.” But most of the people in the industry who happened to be African American or from other cultures sort of had to go along with what was dished out to them in order to make a living. The only way to escape that is to go out on your own and see if you can build something that is more in line with what could build up our people.

Later in the podcast, Sullivan explained why it was important for younger generations to see him working into his 80s, constantly learn about the ever-changing artform of animation:

Why I stay out here even at my age is so [young people] can see, when they look at me as an old man, I work with computers, and my wife works along with me. We make the content. We work with young musicians, artists, and everything, to create some of these things.

Sullivan provided mentorship and education to many artists. Wherever he was in a hiring capacity, he would take chances on young artists who were starting their animation careers. He often spoken to grade school students about pursuing a career in film, and he also sponsored field trips for children to attend movie theaters. Additionally, he taught animation at the Art Institute of California in Orange County.

Sullivan is a key part of the 2016 documentary Floyd Norman: An Animated Life which includes numerous video interviews of Norman and Sullivan together from across the decades, a taste of which can be seen in that film’s trailer.

During his career, Sullivan was honored twice by the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame and won an Emmy for his work as a timing director. He is survived by his wife Ethelyn O. Stewart, their son Leo Jr., and daughter Tina.

Tributes to Sullivan have been flooding social media since the news of his passing. Afrokids.com published a message across its online accounts:

The Twitter account for Floyd Norman: An Animated Life posted a touching tribute to Norman’s close friend and long-time professional colleague:

Our friend Leo Sullivan has passed on.

He was a legend in the animation community, using animation and filmmaking to share Black History with U.S. high school students in the 1960s.

Take a moment to celebrate Leo with this tribute.

Rest in peace, Leo. pic.twitter.com/vq8D0kIDth

— Floyd Norman: An Animated Life (@FloydNormanDoc) March 29, 2023

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse director Peter Ramsey tweeted:

RIP to a great and real one. Thank you, Leo Sullivan. https://t.co/KxhyUOvdBQ

— Peter Ramsey (@pramsey342) March 29, 2023

Walt Disney Animation vfx supervisor Marlon West shared a charming anecdote:

On our “Great Day In Animation” shoot, Leo Sullivan and his family were the first to arrive and among the last to leave. There were 3 generations of professionals there and he is among the folks of whom we all stand on the shoulders of. Thanks Leo, for helping open the door. 🖤🙏🏾 pic.twitter.com/yPh8IAccmA

— Marlon West (@marlonw) March 29, 2023

Bruce W. Smith, creator and executive producer of The Proud Family and supervising animator of The Princess and the Frog villain Dr. Facilier, tweeted:

Leo was a legend for real. My first ever job in this business was in a studio working under Leo, Floyd and the ever elusive, extremely talented Phil Mendez.

All black men.

Leo taught me what to expect as a black man entering the animation industry.

Thank you brother Leo. https://t.co/WuX5yeuH72

— Bruce W. Smith (@BruceAlmighteee) March 31, 2023

.png)