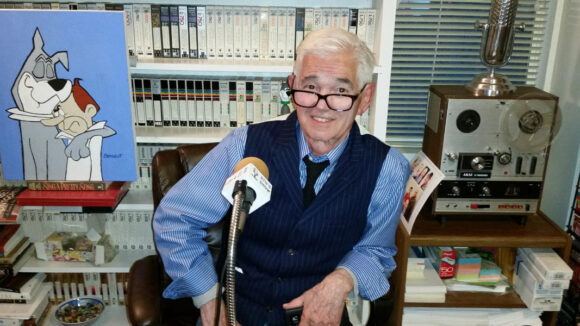

Tony Benedict, Longtime Hanna-Barbera Writer And Story Artist, Dies at 89

Tony Benedict, one of the defining writer–storyboard artists of television animation’s formative years, has passed away at the age of 89.

A Marine Corps veteran who arrived in Hollywood with a sketchbook, a camera, and an appetite for humor, Benedict became an essential creative voice at Hanna-Barbera during the studio’s most explosive decade.

Little is known about Benedict’s early life, but after his discharge from the Marines in 1956, he loaded up his Studebaker and headed for Burbank. “I drove out here in my old Studebaker, 49 Studebaker, and came from a life in the Marine Corps to Walt Disney Studio in 1956,” he recalled in an interview hosted by The Animation Guild, embedded below.

The change was dramatic and joyous. “Was it a culture shock…? Yeah, that’s a soft way of putting it. It was… exhilarating. Everyone there could draw… everyone was drawing all the time and working on Sleeping Beauty.”

At Disney, he entered the animation training program, worked as an in-betweener on Sleeping Beauty, and helped repurpose classic shorts for the Disneyland TV series. “We’d take out whatever material was there… and adapt it for the Wonderful World of Color show,” he said. Looking back, he likened the studio to “the old medieval guilds… passing on information one on one.”

After a round of layoffs, Benedict moved to UPA to assist on Mr. Magoo and discovered he had a natural instinct for writing. When he and writer Phil Babet submitted a script to the fledgling Hanna-Barbera studio, Joe Barbera bought it and hired Benedict. “They hired me but didn’t hire Phil because I could draw and Phil couldn’t,” he said. From that point on, Benedict found himself at ground zero of TV animation’s first great boom.

Hanna-Barbera in the early 1960s was, in Benedict’s telling, a place of dizzying output and relentless invention. “There was a time in this animation business — we used to call it the cartoon business — that was different than any other period,” he said. “From 1957 to 1967, Hanna-Barbera pretty much owned the animation business… Everyone was working for them because the business had died outside Disney.”

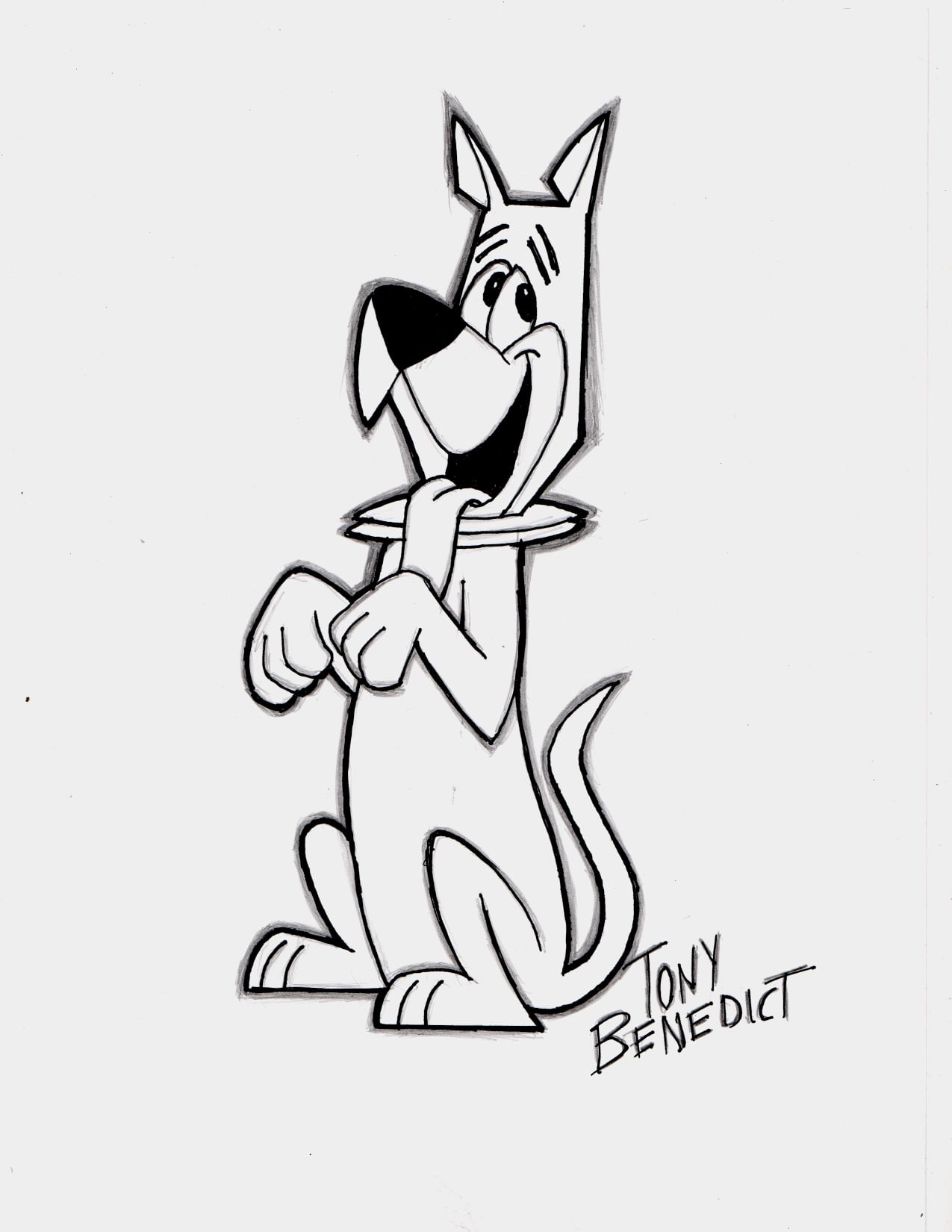

He contributed writing and boards to The Flintstones, Top Cat, The Jetsons, Magilla Gorilla, Huckleberry Hound, and countless shorts and interstitials. He is also the creator of one of The Jetsons‘ most popular characters, Astro the dog. The workload was heavy, but the freedom was exhilarating. “We were writing and making these films, and they would pretty much get on the air the way we had written them,” he said. “There was no such thing as a Bible… We learned about these characters from doing them.”

Pitching was direct and personal. “Joe was really the only one. He had to be pleased. And he spoke only to God,” Benedict joked. Episodes would often come in short, and Benedict would be asked, on the spot, to come up with new material. “Whenever they were short, Hanna would ask me if I could give him two and three-quarter minutes… and I’d have to fill that up.”

According to Benedict, the mood at the studio was loose, generous, and relentlessly funny. Everyone caricatured everyone else. “That was the language of the studio,” Benedict said. “If you could get a laugh… you had a better chance of getting a raise from Joe Barbera.”

In the late 1960s, Benedict pursued a longtime dream: making his own animated special. When his Christmas story about two bear cubs was turned down internally, he left the studio. “I pitched it… and he passed on it,” he recalled.

Undeterred, Benedict produced, wrote, and directed what eventually became Santa and the Three Bears, an independently financed feature that found its way into theaters and became a seasonal TV staple.

The film’s difficult distribution saga hardened Benedict. “I was very bitter about it,” he admitted. “I just got out of the animation business.” But the hiatus didn’t last. By the 1980s, he was back at Hanna-Barbera as a writer and story editor on the revived Jetsons, followed by stints on The New Yogi Bear Show, Beany and Cecil, Tiny Toon Adventures, Tom & Jerry Kids, and many other television series.

Later, Benedict reinvented himself yet again, moving into early computer games. Though he initially knew nothing about the technology, he found that his instinct for visual storytelling translated. “I didn’t know anything about computers, but I knew animation,” he said.

In retirement, Benedict devoted himself to preserving the history he had lived. Throughout the 1960s, he had carried a camera everywhere, shooting 8mm footage of office antics, studio basketball games, and daily life at Disney, UPA, and Hanna-Barbera. He spent his later years restoring the films and photos, as well as gag drawings by colleagues like Jerry Eisenberg, Willie Ito, Tony Sgroi, and Corny Cole, with the goal of creating a documentary about the era. “I see it as trying to capture all that fun we had,” he said. “It’s like archaeology… mining all of the visual treasures.” His Facebook profile is an absolute goldmine of incredible photographs and amusing anecdotes.

Tony Benedict leaves behind a lifetime of characters and a load of enduring laughs. His work helped define the sound and shape of televised cartoons, and his relentless recordkeeping has helped preserve one of animation’s most charming eras.

All photos courtesy of Tony Benedict’s Facebook page.

.png)