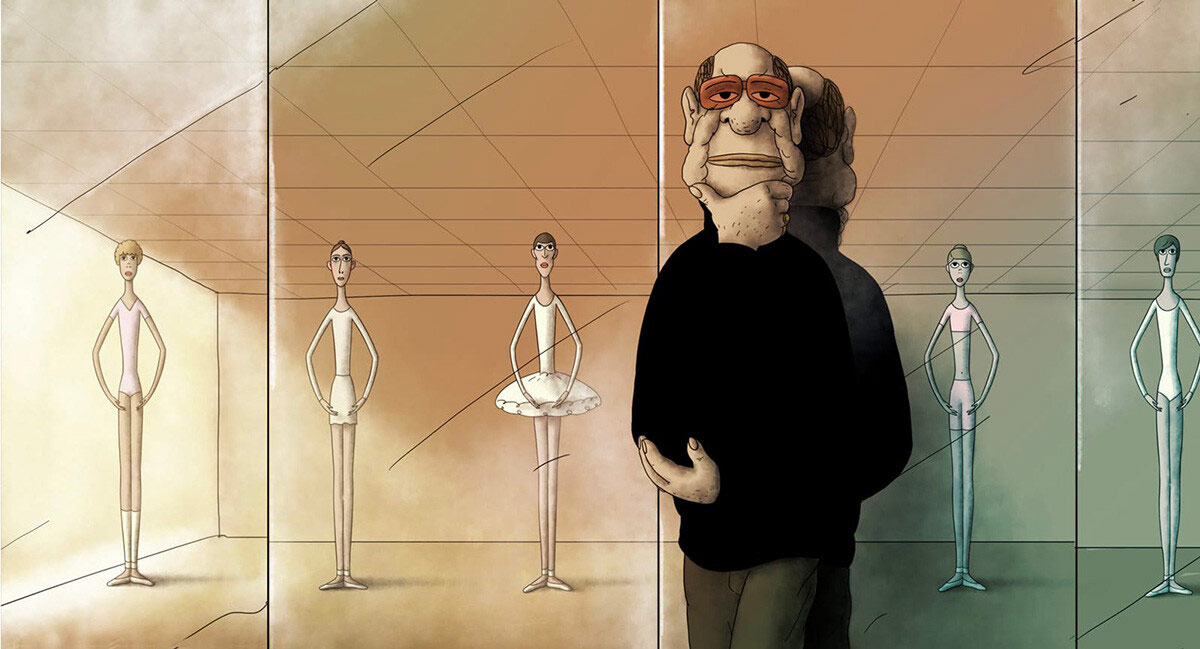

Anton Dyakov, Director Of The Oscar-Nominated ‘Boxballet,’ On Crafting An Unconventional Love Story

Anton Dyakov’s Boxballet is one of two hand-drawn animated shorts nominated for an Oscar this season.

An unlikely love story between a rough-and-tumble boxer and a delicate ballerina, Boxballet is a study in contrasts and commonalities. Its storytelling is heightened by the dialogueless script that takes full advantage of animation’s graphic power. The film was produced by the CTB Film Company and Saint Petersburg, Russia’s Melnitsa Animation Studio.

Boxballet is set in early 1990s Russia, during the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a critical turning point in the country’s history. As Dyakov tells Cartoon Brew, the characters “find themselves at this turning point just like so, so many people back then. . . . I want us to think about what it will be like for them in the future, and whether they’ll have any future at all.” With the current hostilities in that region, the meaning of the film has gained an urgent and new poignancy.

In the following interview, Alex Dudok de Wit spoke with Dyakov about how he structured his story, the differences between animating boxing and ballet, and why he chose to include a single word of dialogue in the film.

Cartoon Brew: How long, overall, did you spend making this film?

Anton Dyakov: A year and a half. Most of the time was eaten up by tinting and shading; that process turned out to be the most routine and tedious part. That procedure required not only time, but a steady hand from the person who helped me implement it.

You made the film at Melnitsa Animation Studio, which you told us has “extensive resources for producing hand-drawn animation in the academic style.” Can you elaborate on this? How did you come to work with the studio?

Dyakov: I didn’t set a specific goal to seek out a particular studio on this project. My script for Boxballet had already gotten a couple of funding rejections from different studios, and I was already thinking about doing something else, like a book design, or something else swimming around in my head. But then I saw an announcement that Melnitsa studio was having a script competition, and the winner would get funding for their project. So I submitted my script to the competition, and lo and behold, it won. So you might say our collaboration happened by itself, that we were brought together by circumstances, and I accepted this as the best thing for the project and for myself. I believe that there’s no such thing as coincidence. This had to happen, and it did happen. The whole time I felt like the studio was genuinely interested in my project. They really wanted me to do things the way I thought they should be done, and I’m grateful for that.

What struck me about Boxballet is that it tells its story very economically. A good example is the way you tackle the scene with the stolen purse: we don’t see the boxer recovering it, but the next shot shows him returning it to the ballerina, which says all we need to know. It feels like you tell 25 minutes’ worth of story in 15. Was the film initially supposed to be longer?

Dyakov: I’m more inclined to keep things on the short side; I don’t like it when things are drawn out. I wanted to use a relatively compact timeframe and dynamic narration to bring the viewer to an emotional reaction. That was my ambition. So while working on the script, I decided for myself to let go of a lot of things, like, in the boxing-match scenes, there were originally a lot of twists and details involved. There was a moment where I got sick and ended up lying in a hospital for two weeks, so I decided to do more work on the script while I was there. And that’s when I realized that the key aspects of the story weren’t the turning points themselves, but the characters’ reactions to them, and as soon as I clarified that aspect of the material, I immediately felt like the story could breathe and the narrative was no longer weighed down.

The story depicts sexual harassment in a professional context. Why did you bring in this subject?

Dyakov: Addressing that was never intentional. Anyone who works in animation can tell you that it’s not easy to bring up topical issues in a film since so much time passes from conception to realization, and your whole context, including timely issues, will vanish before you get your work to the viewer. And it’s no secret that stories like this are not uncommon in the world of ballet. So I would say that it’s in the film not because I had some desire to raise a topical issue, but because it just so happened to be that way.

There is just one word of dialogue in the film: “Dumbass.” Was that the case from the first draft of the script?

Dyakov: The script used to be much chattier. Olya and Evgeny had dialogue in the scene where they meet, in the kitchen, and there were just a lot of words scattered around the script. Over the course of the process, lines I’d considered important just fell away naturally on their own, without any loss in the storytelling. Believe me, I could even do without the single word that does appear in the film. If I’d taken that out, everything else would still be fine. But I wanted a kind of cherry on top. There’s only one word in the film, and it’s that word. You know, a little treat on the author’s part.

Browns dominate the palette in Boxballet, as they do in some of your other films. What do you like about this color?

Dyakov: I love various approaches to color. But I’m still a graphic artist at heart. Sepia, sauce, charcoal, graphite, pastel, ink… these are the materials I find most natural to work with. Of course, working with color is always a puzzle you have to solve, while working with monochrome space is a form of understatement. Warm undertones are important to me, but I like to add variations in warmth and coolness, which I find pretty fascinating. In that sense, I made Boxballet at the junction of color, but also muted with an ochre hue.

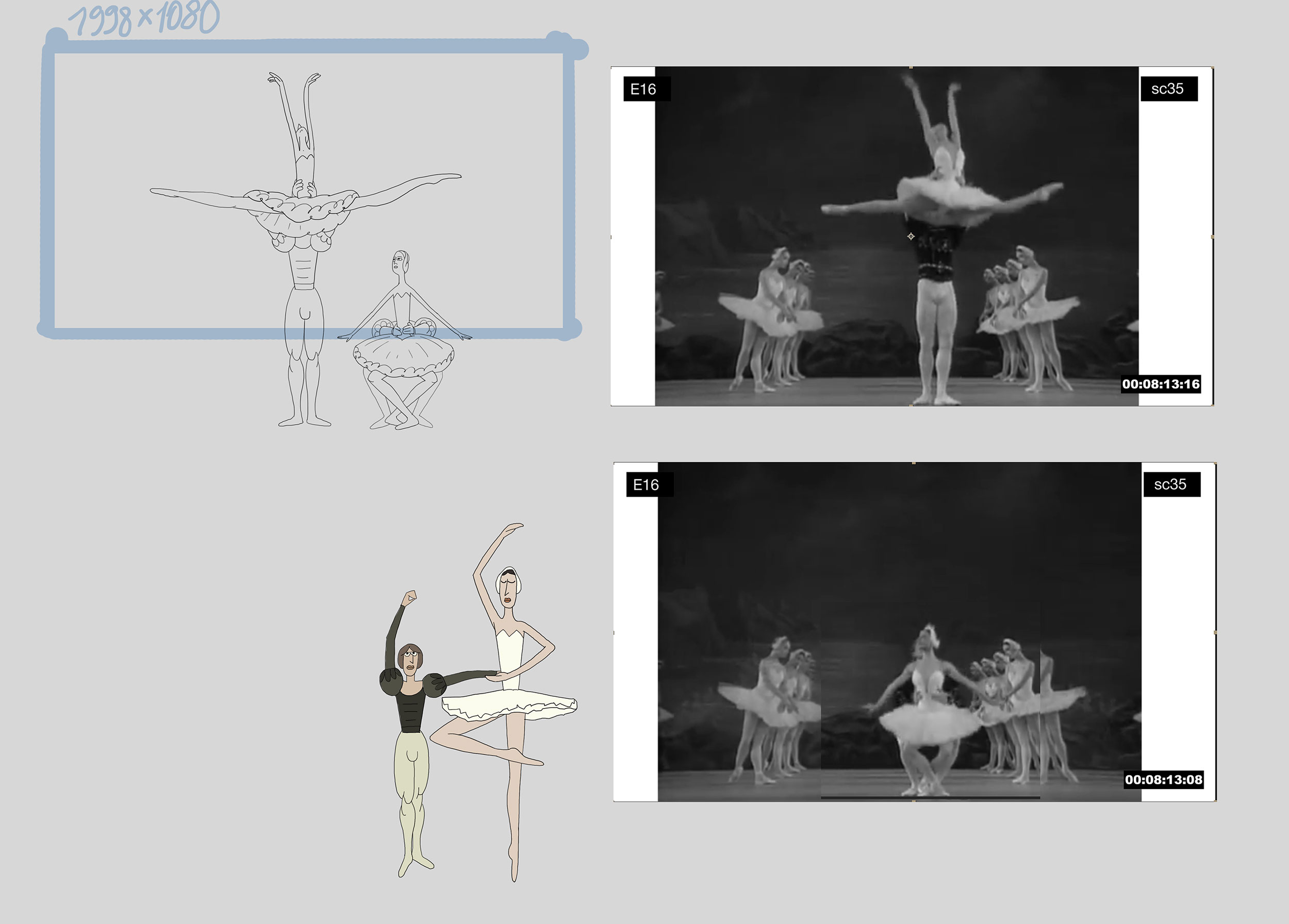

What were the main differences between animating the boxing and ballet scenes? Which was more fun?

Dyakov: We figured out the boxing pretty quickly. But the ballet scenes required some immersion in the material. I looked through recordings of classical ballets with the animators, analyzed the dancers’ movements, and found their internal, plastic logic. We simply had to do this, otherwise it would have been an imitation, an empty shell. Ballet is a very fragile substance: the slightest slip or mistake, and everything falls apart. One mistake, and an otherwise tragic scene can make people in the audience laugh. That experience taught me to be sensitive to things like that. So you have hundreds of videos of ballets with some of the best dancers, but that alone wasn’t not enough. Translating classical ballet into the conventions of animation required immersion, and I’m pleased with how we ultimately handled it.

The characters express themselves mostly through their bodies — their facial expressions change little. This makes sense, as they use their bodies for a living. But was it always clear to you that you would approach the animation in this way?

Dyakov: To be honest, that wasn’t my intention. I did what I thought was necessary without explaining it to myself. The soloist in this work is bodily plasticity. It’s only fitting to use that in a love story between a boxer and a ballerina.

Tell me about the photos on the television at the end. I recognize Yeltsin, and I think Gorbachev…

Dyakov: Those are documentary photos from 1991 to 1993. Yeltsin and Gorbachev are in there. You know, these were signs of the time, a turning point in my country’s history. So Olya and Evgeny find themselves at this turning point just like so, so many people back then. Through my work and the means I have available, I want us to think about what it will be like for them in the future, and whether they’ll have any future at all…

.png)