Stitched Into Motion: Bea Lema Brings Embroidery To Animation In ‘El Cuerpo De Cristo’

Spanish illustrator and comic author Bea Lema’s animation debut, El Cuerpo de Cristo, transforms textile craft into moving images while confronting one of cinema’s most stigmatized subjects, mental illness. The film will be screened this weekend at the International Film Festival Rotterdam in the short and mid-length section.

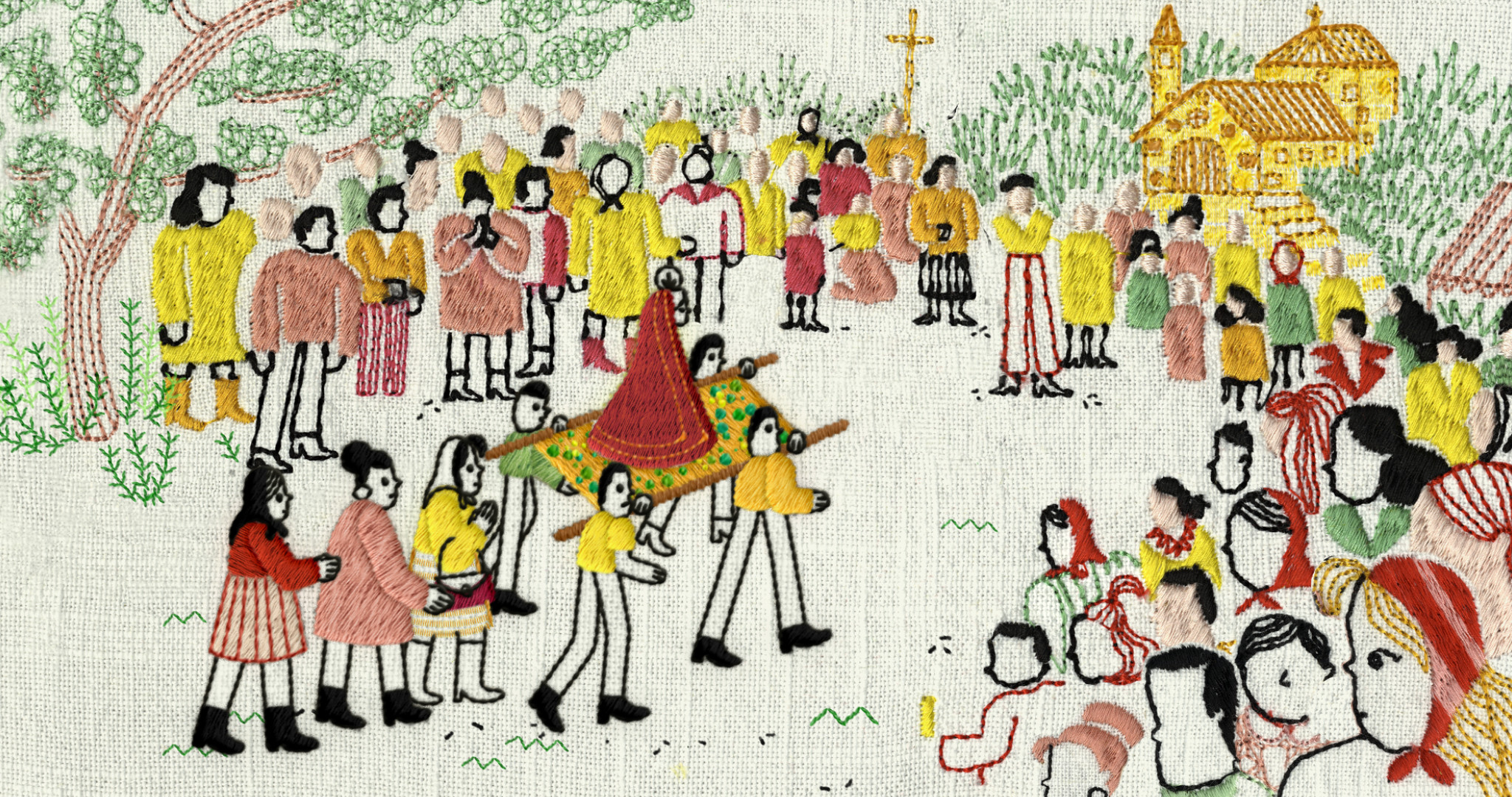

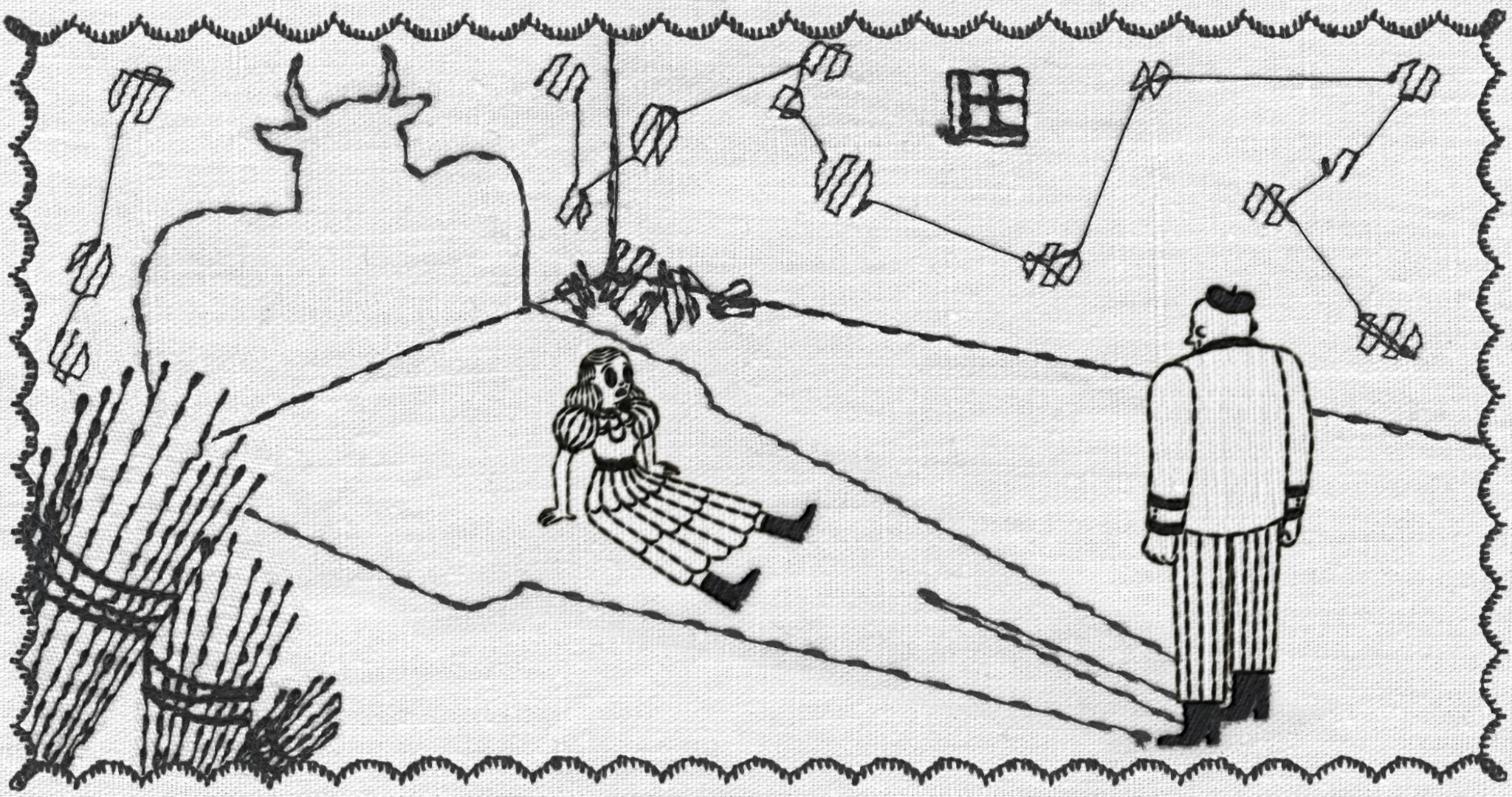

Featuring fully embroidered backgrounds and digitally animated characters meant to look as if they were stitched onto the screen, the film adapts Lema’s award-winning graphic novel of the same name into a concentrated, emotionally precise experience.

The project’s roots stretch back nearly a decade. Lema’s original comic, which she started in 2016 and finally published the definitive version of in 2023, is an autofictional exploration of her mother’s mental illness as experienced through a child’s perspective. Across 175 pages, roughly forty of them featuring hand-embroidered images, Lema combined drawing and textile work to evoke “memory, domesticity, and trauma.”

Bea Lema

The film adaptation, therefore, demanded a radical narrative compression. “The short forced me to do an exercise in synthesis,” Lema tells us. Rather than splitting the perspective between mother and daughter as in the comic, the film centers squarely on the mother, Adela, and her mental deterioration. Misunderstood by both her husband and medical professionals who offer medication without listening to her experience, Adela turns instead to religious and folk rituals for healing, convinced that an unseen force torments her.

For Lema, the key was shifting audience perception away from horror tropes. “Mental illness, especially psychosis and delusions, is still heavily stigmatized,” she says. “Symptoms are often seen as a personal failure, when in reality they’re deeply connected to someone’s life history.”

A newcomer to the medium, although aided by highly accomplished animation producers Iván Miñambres and Chelo Loureiro, Lema first assumed the short’s animation would simply replicate her comic’s drawing style. But she soon began imagining the film as something more textile, extending the book’s embroidery techniques into motion.

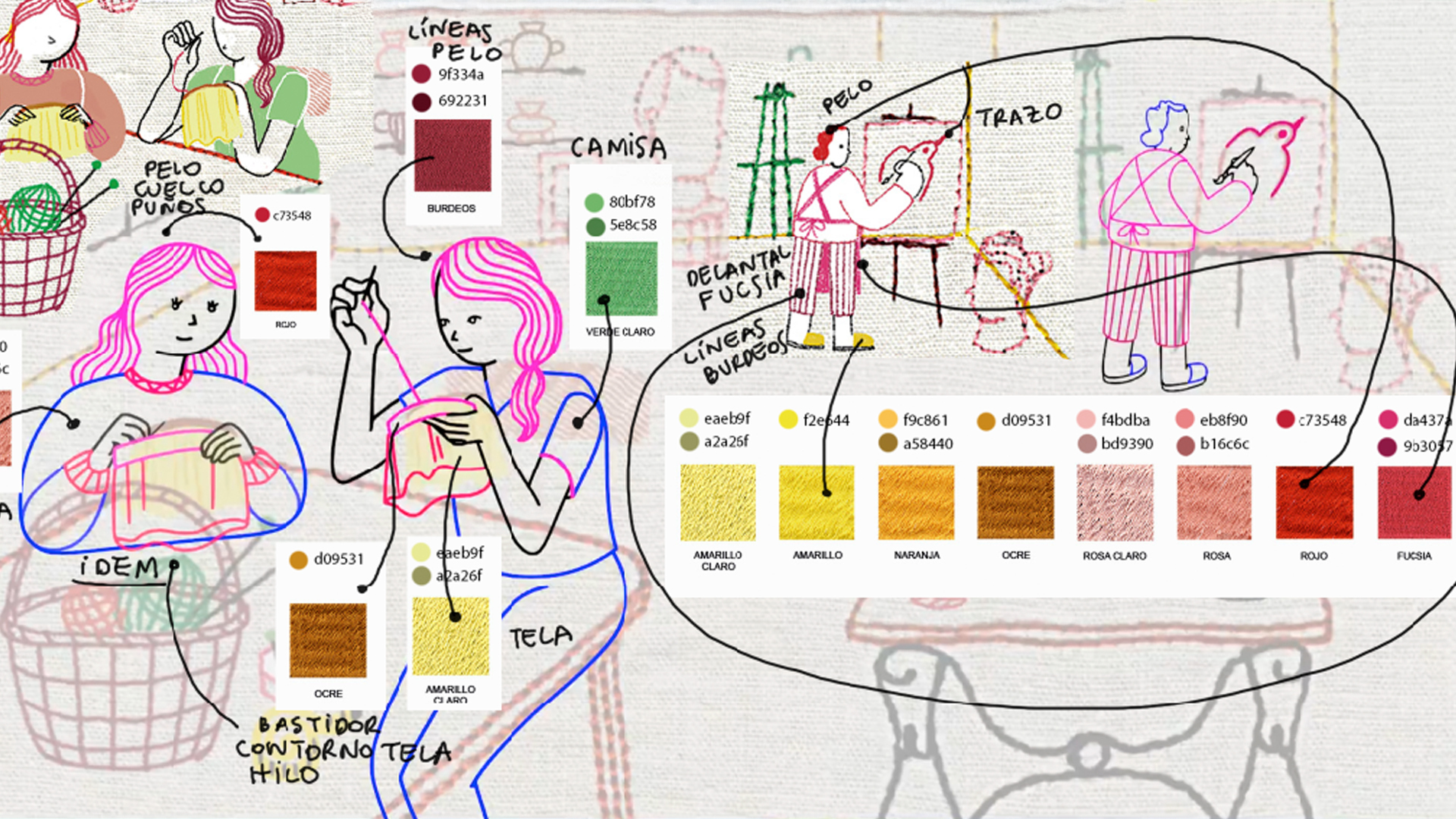

Eventually, the film’s crew settled on a hybrid technique: each background was physically embroidered, then scanned and integrated into digital scenes, while the character animation was produced in 2D using Blender and modified to imitate the spacing and texture of stitches. The decision, however, proved far more technically complex than expected. As Miñambres explained at last October’s Weird Market in Valencia, “the backgrounds are real embroidery, physically produced, but achieving character animation in 2D that actually looked embroidered was very complicated.”

Unlike many films that simulate textile textures digitally, every background in El Cuerpo de Cristo was materially produced before animation began. “All the backgrounds physically exist,” Miñambres elaborated. “They were embroidered, and then we animated characters and props over those real textile surfaces.”

The workflow required constant translation between digital animation and textile craft. Layouts were first constructed in flat color digitally, then handed to embroidery teams with precise instructions about thread colors, stitch types, and fabric applications. More than thirty embroiderers collaborated on the film’s environments, producing physical materials that were later scanned and integrated into the final compositions.

“We used masks and texture treatments so everything feels cohesive, as if it were all made from the same material,” Lema explains. The team created brushes inside Blender that simulate embroidered strokes, allowing characters to visually belong within the stitched environments.

The choice carries symbolic weight. Textile work evokes domestic spaces, maternal care, and intimacy. “Fabric is something that wraps us every day,” Lema explains. “It’s associated with care, with home.” By rendering a story of psychological distress in soft materials, the film reframes suffering through tenderness and empathy, rather than spectacle or voyeurism.

The result is visually disarming: colorful, almost naïve imagery portrays scenes of paranoia, spiritual desperation, religious fervor, and familial incomprehension. Lema embraced this tension during the film’s development and production. She says that the film’s aesthetic softness invites audiences into difficult territory. The film gradually darkens emotionally without punishing viewers visually.

Sound design further elaborates the film’s blend of light and darkness. The film opens with archival recordings captured in Galicia during the 1970s by a Danish anthropologist documenting religious exorcism rituals. The audio is raw: cries, prayers, and communal intensity accompany scenes of crowds, grounding the film in lived cultural practices rather than fictional horror.

Lema says that clarity and accessibility were important in presenting psychosis to audiences unfamiliar with the disease. The film’s emotional authenticity, combined with historical sound recordings and tactile animation, creates a documentary feel within a fictional structure.

Production kicked off rapidly after the comic’s publication. Lema had long fantasized about adapting the book, and when Miñambres and Loureiro came aboard, financing quickly followed through Spanish cultural institutions.

It was only after entering production that Lema grasped the magnitude of the animation work. “A comic is a huge amount of work,” she laughs, “but an animated short is absolute madness.” The twelve-minute film took roughly two years to complete.

The finished short has already made a strong impression on festival audiences. It debuted at Zinebi in November in Bilbao, home to the shorts’ production company, Uniko. Some viewers are shaken by the opening sequence’s visceral audio, while others connect deeply with Adela’s experience or recognize their own family histories in the story. Many want to know how the film was made, surprised that embroidery could function as animation material.

Thematically, El Cuerpo de Cristo continues conversations Lema has pursued through her comics, workshops, and public talks. She frequently presents her work in schools and medical settings, where audiences engage with the representation of mental illness as part of human experience rather than an aberration. “We’re in a moment where we need to talk about this,” she says. “Going to therapy is more normalized now. The next step is understanding that a psychotic episode is also within the realm of human possibility.”

Distribution by leading French company Miyu Distribution ensures strong festival circulation, though Lema remains deliberately detached from expectations. “I’ve done my part,” she says. “Now the film walks on its own.”

While Lema’s debut certainly stands out for its technical achievements, they’re equally matched by its emotional resonance. By translating the tactile intimacy of embroidery into motion, she crafts a work of art that feels handmade in both texture and empathy. As Miñambres reflected, this handcrafted logic informed every decision behind the film, from development through post-production: “It’s a very manual project, just like the story itself. We really embraced that handcrafted process to achieve the final result.”

El Cuerpo de Cristo demonstrates that while technological innovation remains a constant in animation production, the medium continues to find new ways to tell resonant stories and bring fresh perspectives to audiences everywhere.

.png)