How They Did It: Inventing A New Animation Technique For ‘The Physics Of Sorrow’

Even to an animator who once created a film out of his own blood, The Physics of Sorrow proved challenging.

Theodore Ushev has made a habit of adopting a new technique for each of his shorts, matching style with subject. In the Bulgarian experimental filmmaker’s latest work, a melancholic half-hour meditation on the meaning of exile, the method of animation wasn’t just new to him — it had never been used by anyone.

The film is based around encaustic painting, a millennia-old technique that involves mixing hot beeswax with color pigments. In antiquity, Egyptians used it to create finely detailed portraits of the dead on coffins and tombs. More recent artists, like Jasper Johns and Tony Scherman, have used it too, but Ushev is the first to apply it to animation. Below, he tells Cartoon Brew how he tackled the task at the National Film Board of Canada (where he has done much of his work since moving to Montreal in 1999).

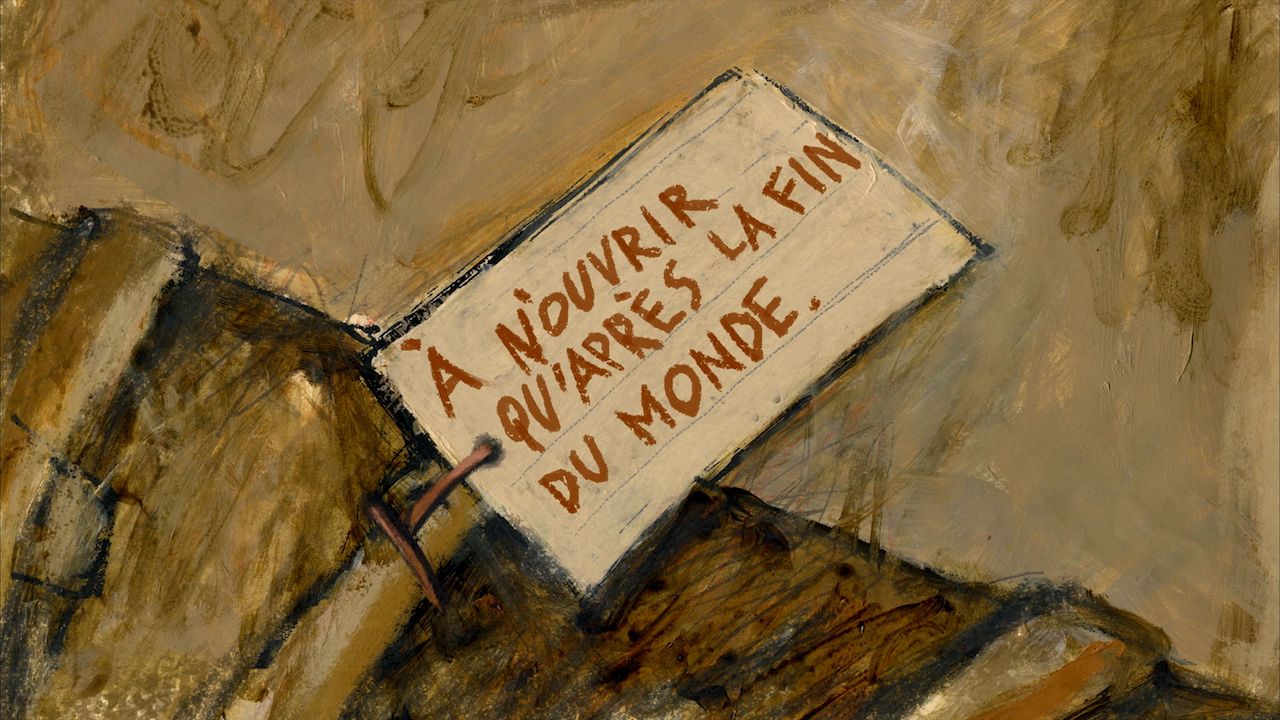

The Physics of Sorrow is based on the eponymous novel by Georgi Gospodinov, the Bulgarian author whose writing also inspired Ushev’s last film, the Oscar-nominated Blind Vaysha. Ushev uses the book as a framework through which to explore his own experiences of immigration, rootlessness, and disillusionment as the optimism of his generation soured. He sees the film as a “time capsule” — a snapshot of a bygone age, like those Egyptian coffins of old.

In the film, the encaustic painting takes on a secondary meaning: the precise recipes were taught to Ushev by his artist father, who plays a key role in the story. The father-son relationship is even reflected in the casting of the narrators, as Ushev explains below.

What follows is an edited transcript of an interview conducted by email. The Physics of Sorrow premiered earlier this month at the Toronto International Film Festival, where it received an honorable mention from the Best Canadian Short Film jury. It screens tonight in competition at the Ottawa International Animation Festival.

Scripting

Theodore Ushev: [Gospodinov’s novel] was a story about me. About my generation. About the kids — “Minotaurs” — born and raised in the small basements of small towns in communist Eastern Europe. I saw the potential of making a film as a kind of time capsule. And Gospodinov writes the same way as I paint.

I think that cinema, especially animation, is very different from literature and from the way writers think. I sent [Gospodinov] drafts of the screenplay. Some of his comments were reasonable. While writing the script, I wanted to personalize the story. Otherwise, I couldn’t have done it. His writing style is very poetic, but there isn’t much action in it, so I had to reinvent the structure, to build a new one. All the action basically comes from my life and my friends’ lives.

Casting

Ushev: First we recorded the French voice, as the script was originally in French. [Renowned filmmaker] Xavier Dolan did an amazing job on it. Then we started looking for an English actor (as this is a Canadian film, we had to work with a Canadian actor).

My producer Marc Bertrand’s wife, Natalie, a voice director, had just worked with Rossif Sutherland on a film, and she said, “He has a great voice!” And I listened to it and yes, that was how I’d imagined the voice in my film would work. Afterwards, he was kind enough to bring his father, Donald, onto the project as a special guest voice.

For me, it was important to give the actors the tonality, the mood, the character I’m looking for. Voicing for animation is completely different from live action. If there’s over-acting, over-reacting, or if it isn’t realistic, you ruin the image. The synthesized image can’t contain the emotions of a real human voice. Animation often clashes with voices. We were careful not to go too emotional, too melodramatic.

Visual development

Ushev: The first ever time capsules were the Egyptians tombs. And they had these beautiful, realistic portraits on the cover of their sarcophagus, created with encaustic painting. Made of melted beeswax and color pigments, they stayed absolutely intact for 20 centuries. So I thought this would be the perfect technique to employ for my film. But I had to not only learn to paint an image or a portrait using this technique, but also invent a way to make it move.

I had a very vague idea about making a film that looks like Gerhard Richter’s photorealism. I got some inspiration from [Ingmar] Bergman and the Czech New Wave directors. But basically, as I found my own style using the encaustic technique, I did it my way.

Animation

Ushev: I had to invent everything — the recipe for the paints, the brushes, the hot plate temperature, the mediums, the set, how to make decor that doesn’t get destroyed when hundreds of frames are animated on top of it. It was pure chemistry. I could have called the film The Chemistry of Sorrow.

The encaustic technique uses hot beeswax mixed with color pigments. There are industrial paints, but the technique didn’t work with them. So, my father gave me some original recipes, and voilà! The magic happened. I imagined that I could change every image with a hot gun, repaint the next one, melt it again. I invented a pretty simple set-up. It had to have a human touch, a DIY feel, a personal look.

At first, I used something like “green screen” effects. I painted the moving figures on green paper, then added the backgrounds in After Effects. After that I found an easier, more natural solution. Paint the backgrounds with gouache and crayons, cover it with more heat-resistant palm wax, change the top with beeswax mixed with paraffin and the figures on top with liquid wax that required less heat, and pigments. This is how I was able to change only the moving figures, without any multiple camera shots in complex settings. Stop-motion paintings.

.png)