From Poem To Puppets: How BAFTA-Nominated ‘Two Black Boys In Paradise’ Became A Stop-Motion Act Of Love

When Two Black Boys in Paradise received a BAFTA Film Award nomination for British Short Animation last month, it marked another high point in a gilded festival run that has already included more than 60 international screenings and 21 awards.

But the BAFTA nod is not the story here. The story is how a deeply personal poem about Black queer love became one symbolic of its creators’ own journeys of openness, love, and self-acceptance.

The Team

Directed by Baz Sells and written by Sells, poet Dean Atta, and Ben Jackson, the 9-minute film adapts Atta’s poem from his collection There is (still) Love Here into a handcrafted, stop-motion world.

Produced by Manchester-based One6th Animation with support from the BFI Short Form Animation Fund, the film follows Edan (19) and Dula (18), two young Black men navigating racism, homophobia, self-doubt, and the fragile courage of holding hands in public. Their refusal to hide becomes transformative, transporting them to a paradise free from shame.

For Atta, that paradise was both literal and emotional.

“There’s a lot of emotional truth in it and a lot of our lived experience,” he explains. “Paradise, while it’s presented as a real place in the film, is also a kind of state of being with someone who just gets you and being with someone that you feel completely safe and loved and accepted.”

Atta and co-writer Ben Jackson have both been in long-term relationships for eight years. That stability, after confronting their own self-doubt and the fear, became central to the film’s emotional architecture. “We’ve both had experiences where we’ve been afraid to hold our partner’s hand in public,” Atta says. “Learning to love and accept yourself can be helped along by having a partner… but sometimes it is about an internal journey.”

Jackson first encountered Atta’s poem at a Berlin reading in 2019. “I’d come out by then, I didn’t come out till I was 30, but I was still very much struggling with self-acceptance,” he recalls. “I just went away and couldn’t stop thinking about that poem.” By the summer of 2020, in the isolation of Covid lockdowns, he reached out to Atta about a collaboration. What followed was a five-year process that Atta describes as an unexpected but joyous education.

“I didn’t know that was called development,” Atta laughs when speaking of those early Zoom calls and pitch decks. “Every step of this journey has been a learning experience about how film works and how films are made… and then how they are sent to festivals and awards. It’s been such a steep learning curve.”

From Poem to Puppet

Atta’s original poem offered only minimal visual description: two Black boys in paradise. The rest had to be invented.

“When I wrote the poem, I relied on people having a concept of paradise, perhaps from Christianity, from the Garden of Eden,” Atta says. Raised in the Church of England, he imagined a reclaimed Eden populated by two Black queer characters. During development, he began suggesting details: snow-capped mountains inspired by the Scottish Highlands, a loch rather than a generic lake, and contrasting hairstyles, dreadlocks and an afro, reflecting his own formative years. “Hair was a really big, important part of my experience as a Black man,” he notes while chuckling about his now hairless head.

Much of the narrative expansion emerged through conversation. The market confrontation, the police stop, and the choreography of public hostility were shaped through long discussions about lived experience. “We had a lot of time to talk about what our experiences were, what we wanted to say about holding hands as a gay couple in public, what we wanted to say about the relationship between Black men and the police,” Atta explains. “It was a lot of talking.”

Jackson and Sells translated those conversations into a script and storyboard, working closely with storyboard artist Avia Shelts-Brown. But the leap from 2D planning to 3D stop motion introduced another layer of complexity.

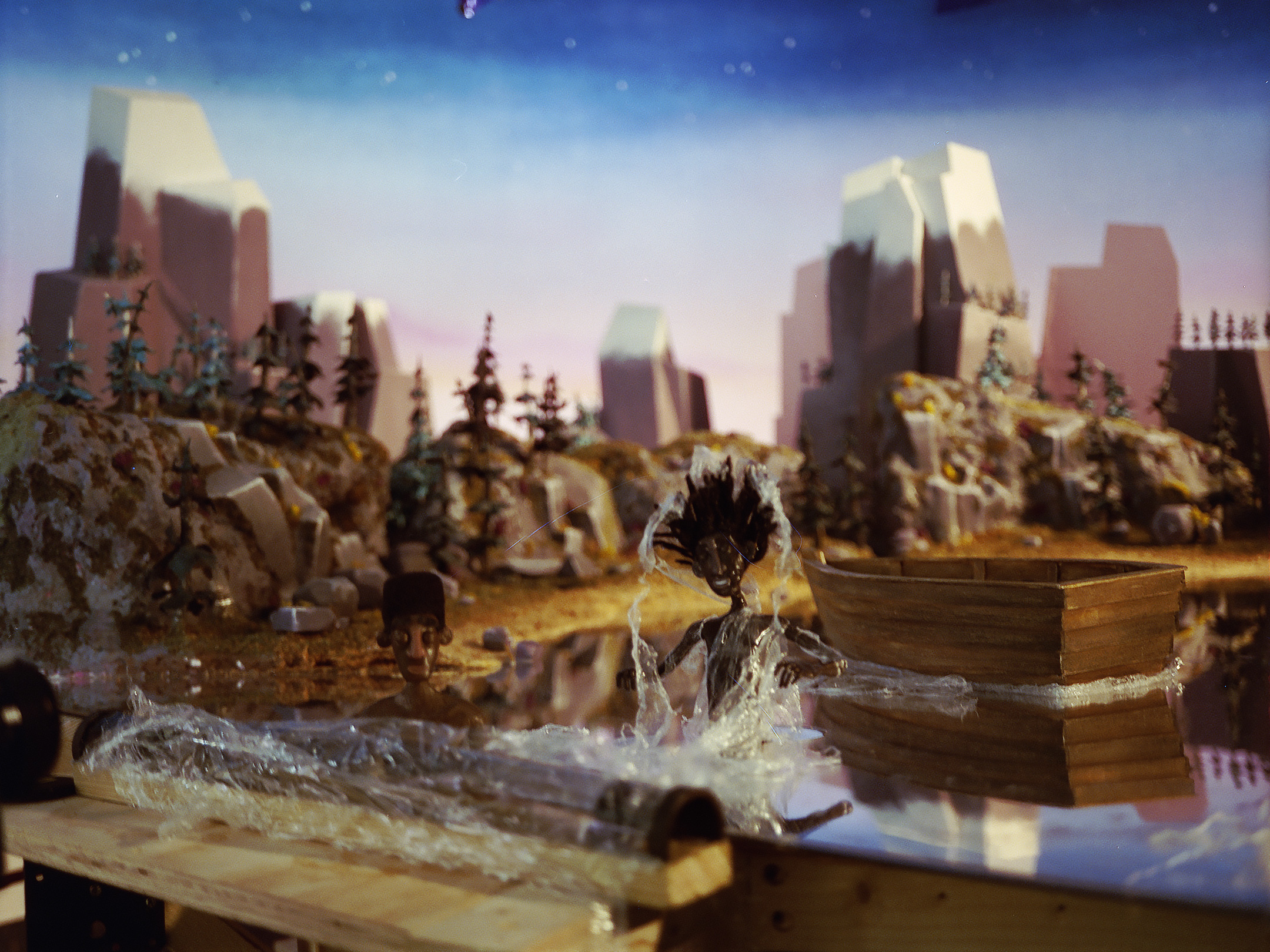

“We had this very clear idea of paradise in 2D,” Jackson says. “But then it was like, how do we turn this into a 3D stop motion set?” Water, notoriously difficult in stop motion, became a central technical challenge. The team wanted reflections captured in-camera. “There was definitely some R&D time needed,” he says. “How do we achieve that reflection? How do we create waves?”

Early puppet tests explored complex internal head mechanisms and silicone faces to maximize expression. Budget and feasibility ultimately led to solid heads with replaceable mouthpieces. “The animators did such an amazing job of getting so much emotion out of those faces,” Jackson says. “Considering the constraints, the way they moved the eyebrows and eyelids—it was incredible.”

Atta admits he had to be convinced about adapting his poem to stop motion. “When they said stop motion, I worried it could be clunky.” That concern evaporated once he saw the animatic and early designs. “It’s the opposite of clunky. It’s incredibly fluid, almost balletic. It looks like a dance between these boys.”

The aquatic sequences, in which Edan and Dula glide underwater before surfacing into their Edenic refuge, evoke Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight, a reference point the cinematography team consciously embraced. Atta finds those scenes especially resonant. “When they’re in the water, they seem incredibly free,” he says. “It reminds me of becoming more comfortable in the water since being with my partner.”

Love at the Core

The production itself became an extension of the film’s ethos. “Everyone who got involved really believed in the project and wanted to be there,” Jackson says. Cast and crew bonded deeply; some even took trips together during production. “I’m so grateful for the relationships this film has brought me,” he adds. “It was a journey of self-acceptance for me.”

That sincerity is evident in every frame on screen. The film doesn’t sensationalize to elicit easy reactions. Hostility is present, but it does not define the boys or their experiences. Instead, quiet, defiant love anchors the narrative. “Love is at the heart of it for the three of us,” Atta says, referring to himself, Jackson, and Sells.

Crucial Support

The BFI Short Form Animation Fund provided crucial financial backing alongside the U.K. animation tax credit, which was slightly lower at the time than it is today. Jackson describes the financing journey as precarious, with failed applications strengthening the eventual pitch. “We got to the stage where we couldn’t imagine a world where we didn’t get to make this film,” he says.

Now, as the short continues its awards run and streams in the U.K. on Channel 4 (distribution in other major territories, including the U.S., is being finalized), Atta reflects on what it means for the poem to reach audiences who may never pick up a poetry collection. “I’m dyslexic,” he says. “I love that this poem is being delivered in this beautiful film because it can reach people who don’t read poetry books.”

For him, the adaptation has been transformative. “It’s been such a journey… to go from development to production to festivals to BAFTA nominees. Every screening was a delight.”

Return to Animation?

“Yes,” Atta says without hesitation when asked if he’d like to adapt any of his other works in animation. “Maybe something feature-length this time. I can see how my stories can reach a much wider audience through film. Animation is such a beautiful type of storytelling.”

In Two Black Boys in Paradise, that storytelling feels less like escape and more like reclamation. Its handcrafted Eden allows two young men, and eventually many more couples, a place not only to exist, but to love openly, joyfully, and without apology.

.png)