EXCLUSIVE: John K. Talks about his “Simpsons” Opening

Last year, The Simpsons commissioned an opening couch gag from British street artist Banksy that contained a cockeyed look at the working conditions of overseas animators. This year, which marks the show’s remarkable 23rd season, the producers of the mustard-family went a step further and debuted a new couch gag last night by Ren and Stimpy creator John Kricfalusi.

Banksy mocked the idea of mass-produced corporate art in his opening, but his message was muddled because it was made using the same system he was satirizing. There’s no such confusion in John’s approach, which he produced on his own. John’s opening is, in fact, far more subversive because he focuses almost exclusively on making a pictorial statement, relegating the show’s dominant literary elements to the back seat. In 35 short and sweet seconds, he liberates the animation of The Simpsons from years of graphic banality. The visual look of the show, which has been so carefully controlled by its producers, becomes a giddy and unrestrained playground for graphic play, and the balance of creative authority is shifted from the writers’ room to the animators in one fell swoop. Now that’s revolutionary.

On a personal note, I worked on the revival of Ren and Stimpy nearly ten years ago, and artistically, this is not the same John Kricfalusi that I remember from that time. Like any painter or filmmaker worth their salt, John doesn’t stay still, constantly evolving, growing, experimenting, and challenging audiences with new graphic concepts. He continues to be, in my book, one of the most exciting and influential artists working in animation today. Whether everything works perfectly in this opening is besides the point. As John says in our interview, “The day I make a perfect cartoon is the day I’ve run out of creativity.”

In our interview, we talk about how the opening came about, Matt Groening’s reaction to it, how his style has evolved in recent years, and his switch from Flash to Toon Boom. (Note: This is an edited version of an interview that was conducted via email this past weekend. Click on any of the images for a larger version.)

Question: First things first, how did you end up animating an opening for The Simpsons?

John Kricfalusi: Matt Groening and Al Jean [executive producer] asked me to do it. They showed me an opening that Banksy did that satirized the animation production assembly line system in Korea and told me it was really popular, so they wanted to do something similar with me.

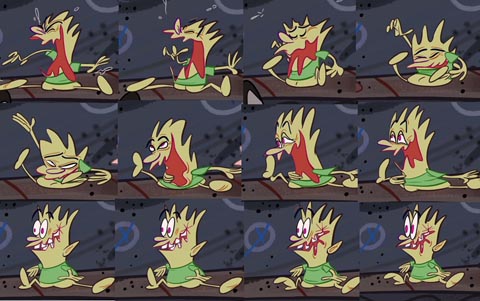

At first they just wanted me to do a storyboard and have their regular crew animate it. If we had done it that way, no one would even have known that I had anything to do with it because it would have ended up on model and all pose to pose. I showed them the Adult Swim shorts I had been doing and pointed out that the way things happened was even more important than what was happening in my work. You can’t write visual performance. You have to actually draw it.

This project was the most fun I’ve had in years. It has really hammered home (to me) the importance of animation in animation. I think it’s possible to bring animation back to this country and make the core of it fun again, not be a mere tertiary addition to some high concept or executive’s “vision.” The pure act of animating is the most fun part of animation. I am so grateful to Matt for letting me have some real fun this summer.

Q: For a show that is notorious for being ‘on-model’, it doesn’t appear that they gave you many (if any) restraints or guidelines. Did you have to show them storyboards or designs beforehand? Did they ask for any changes or cuts?

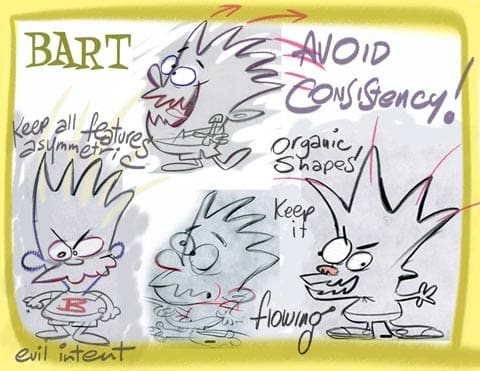

JK: I did some character models to give them an idea of how I would draw the characters as caricatures of the Simpsons. They all made it very easy for me and the more rules I broke, the more they seemed to like it. I tried not to break any rules in the characters’ personalities, just in the execution of the visuals. I didn’t follow any models–not even my own.

Q: How did they react to your ideas?

JK: I had lunch with Al and Matt a couple times and we knocked around some ideas. Matt told me to break all the Simpsons rules. The whole bit is only 35 seconds long so it’s not like we could write a big story. We thought we should just do a quick scene that distills and caricatures the essence of the Simpsons. I only got one note: “Do we need so many reaction poses of Bart?” Tom Klein, who produced Ralph Bakshi’s Mighty Mouse cartoons with me eons ago, is the producer of The Simpsons and he was very helpful and supportive on the project too.

Q: The thing that strikes me watching this is that this isn’t the John K. cartoon of ten years ago, or even five years ago. Your style has evolved greatly in the past few years, in terms of graphic complexity and experimentation. Has this been a conscious effort to move in a new direction and have you noticed the changes yourself?

JK: It’s because of a number of factors. I am just doing small projects now, so I do more of the work myself. When I was running a studio with fifty artists, I spent a lot of time training, directing and explaining what I wanted. You can’t explain animation in words. I did as many drawings as I could, but they tended to be rough poses that after going through the assembly line process eventually get toned down.

Katie Rice influenced me a lot. She showed me all kinds of funny abstract expressions in anime cartoons and her own drawings were super cartoony, original and cute all at the same time. The way she applied the abstractions from anime (and other influences) she liked was a revelation to me. Around the same time, thanks to Jerry Beck and Mark Kausler I started watching a lot of previously lost 1930s rubber hose cartoons: Fleischer Talkartoons, Lantz Oswalds, Ub Iwerks and Terrytoons. For decades these cartoons have been derided by cartoon historians and even some of the animators themselves.

These cartoons have attributes that far surpass their seeming limitations. They were extremely inventive and the animators were encouraged to do what comes naturally to cartoonists and animators. They were allowed to draw and animate in their own individual styles. In the early 1930s, there were no set bible of rules for how to animate. The medium was too young. Every animator figured out their own unique ways of moving things. I absolutely love watching Grim Natwick, Bill Nolan, Irv Spence, Carlo Vinci and others’ animation because it is all so unique. And the cartoons were musical: all cartoons from the 1930s to the 1950s were timed to musical rhythms. This gave everything that was happening an underlying sense of fun. The tempo was the structure of the action.

Amid, you also inspired me when you showed me a lot of 1950s animated commercials–highly stylized stuff that was beautifully and inventively animated. In a couple of my recent Adult Swim shorts, I tried to caricature some of my favorite designy commercials. Those 50s commercials as you know were all animated by the same guys who learned their craft on rubber hose cartoons in the 1930s and honed their principles on 40s cartoons. Their stylized stuff in the 50s reflects all that foundational skill and knowledge even though it seems like they are breaking the rules.

Q: So much of this goes appears to go beyond the pose-to-pose animation that you did on Ren & Stimpy and into more adventurous straight-ahead animation territory, right?

JK: I’m bored with pose to pose animation like we did at Spumco where the only control we had over the look of the cartoon characters’ acting was in the held layout poses. This time I wanted to try moving the characters in crazy fun ways, not just looking funny each time they come to a stop. The way we used to do it was: the characters would strike a funny pose, then basically inbetween into the next funny pose, but between the poses, nothing much interesting happened. It was a compromise between the Forties cartoon production system and the practicalities of Saturday Morning television budgets and schedules.

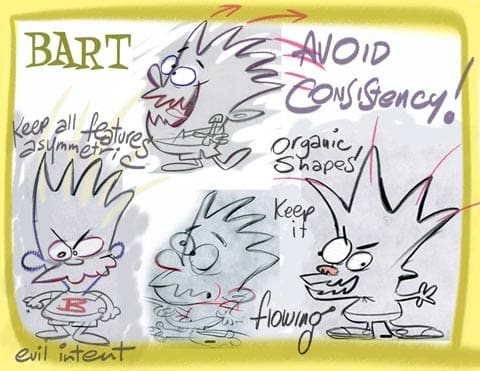

The inbetweens are as fun to me as the bookended emotions you are aiming at. No one is happy one instant, and then mad the next without some kind of unique transition. Pure inbetweening makes the transition mathematical and cold. In reality, a lot of indecision and emotional torture happens between two different emotions or even just two thoughts. If you freeze frame live action you can see that there is no such thing as inbetweens. Live actors’ faces distort and mutate all over the place getting from one emotion to the next. Rod Scribner used to do that in his animation and it added a lot of extra “reality” and richness to his acting. His characters just felt more alive and real than other more cautious animators. You don’t see all the individual frames in rich movement, but you feel them.

Q: Did you animate the piece or did you have a team of animators?

JK: I animated the 2D stuff. John Kedzie animated the CG bits. Sarah Harkey and Tommy Tanner did the assistant animation.

Q: You switched a while back from Adobe Flash to Toon Boom. Has the shift in software influenced your style or affected your workflow in any way?

JK: Completely. It allows me to try lots of things and delete them if they stink and quickly do them again. I get bored really easily. I don’t like to rely on formula. I like every scene to be different than the last scene. I can’t follow rules — even my own. Animating in almost real time allows me to have fun.

Q: What’s something new you tried out in this piece that you think worked really well? And that didn’t work as well as you’d thought?

JK: I’m still struggling with camera moves. I’m using Toon Boom Harmony because it has a great brush tool and it’s easy to animate with, but some of the technical tools like cameras are very awkward and anti-intuitive. I don’t know what new things I tried except that it’s the first time in years where I got to animate that much stuff. If you freeze frame it you may find some surprises which might be considered new.

Well, here’s something in general: I am applying classic principles of squash and stretch, overlapping action, anticipations and overshoots, slow ins and slow outs, etc…but making the drawings that do the work of all these principles be more abstract and nonsensical. For example, when a character squints his eyes during an anticipation, I might just create one eye and draw it as a cartoony graphic, rather than literally drawing the two eyes squashing and squinting in the traditional graphic way we have been doing for 80 years.

Q: What’s your answer to those who will look at this and inevitably complain that you’re breaking many of the drawing principles you’ve espoused over the years like maintaining volume of forms and having facial details wrap around forms?

JK: The Simpsons are very stylized to begin with and their features do not wrap around their forms. Neither do 50s UPA style cartoons. But they do have hierarchy and internal logic of some kind. They use controlled abstraction rather than arbitrary unbalanced distortion.

I have explained many times that learning fundamentals does not mean that your goal is to draw like Preston Blair or Milt Kahl. Good drawing starts with having control and knowledge of how things work and look. Once you have some fundamentals, you can use cartoon license for effect and entertainment. If you can’t draw very well to begin with you are not breaking rules as part of your style, you are just breaking them by accident and you will never be able to make your fingers do what your brain imagines. Good drawing and animation isn’t one simple skill or talent. It’s a lot of different skills that you have to balance together and no one has them all. You just keep learning and studying throughout your life or you become bland. Is the cartoon perfect in any way? Of course not. The day I make a perfect cartoon is the day I’ve run out of creativity.

After the jump, watch a series of behind-the-scenes video clips showing the production process:

STORYBOARD/ANIMATIC

ROUGH ANIMATION

COLORED ANIMATION

COMPOSITE WITH CG BG

.png)