‘Mouse in Transition’: A Gong Show with Eisner and Katzenberg (Chapter 16)

New chapters of Mouse in Transition are published weekly on Cartoon Brew. It is the story of Disney Feature Animation—from the Nine Old Men to the coming of Jeffrey Katzenberg. Ten lost years of Walt Disney Production’s animation studio, through the eyes of a green animation writer. Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg. Since 1989, Hulett has served as the business representative of the Animation Guild, Local 839 IATSE, a labor organization which represents Los Angeles-based animation artists, writers and technicians.

Read Chapter 1: Disney’s Newest Hire

Read Chapter 2: Larry Clemmons

Read Chapter 3: The Disney Animation Story Crew

Read Chapter 4: And Then There Was…Ken!

Read Chapter 5: The Marathon Meetings of Woolie Reitherman

Read Chapter 6: Detour into Disney History

Read Chapter 7: When Everyone Left Disney

Read Chapter 8: Mickey Rooney, Pearl Bailey and Kurt Russell

Read Chapter 9: The CalArts Brigade Arrives

Read Chapter 10: Cauldron of Confusion

Read Chapter 11: Rodent Detectives and Studio Strikes

Read Chapter 12: Disney Dead-Ends and Lucrative Mexican Caterpillars

Read Chapter 13: Basil Kicks Into High Gear

Read Chapter 14: “Call Us Mike and Frank”

Read Chapter 15: The Arrival of Jeffrey Katzenberg

The Black Cauldron producer Joe Hale was not having an easy time with new studio boss Jeffrey Katzenberg. Katzenberg had seen a rough cut of Cauldron, and had issues. A large chunk of the feature was animated, but Mr. Katzenberg didn’t think the film really came together. The humor was forced and sporadic, the pace lagged. And the Horned King was a spectral cipher (and a county-mile from Vance Gerry’s early version).

Jeffrey asked to see out-takes from the movie and quickly found out that in animation, there aren’t any. Some of the old-timers thought it was ludicrous that Katzenberg didn’t know this basic fact of life, but when you have spent your career doing live-action, why would you?

Jeffrey might have been a cartoon novice, but he learned fast. And he was decisive. When he saw the story reels for Basil of Baker Street, he let the crew know what he thought worked and what didn’t. The story pretty much worked. One element he decided was clunky was the song belted by a barroom singer two-thirds of the way through the story.

“Non-compelling and old-fashioned,” Jeffrey said. A new song-writer with rock-and-roll chops and a voice to match was brought in. The high-profile pop singer Melissa Manchester penned a new tune titled “Let Me Be Good To You,” and also belted it out on the soundtrack. We felt bad for Henry Mancini, who had penned the original, but we understood that Jeffrey was working to make animated features younger and more contemporary. Woolie Reitherman’s animation department was vanishing before our eyes.

Mr. Katzenberg also made cuts and changes to The Black Cauldron, and Joe Hale went to war with him. At a department-wide meeting, Joe stood at the back of the room and fired hostile questions: “How many animated projects have you worked on?”…“What are your qualifications to head up animation?”

Jeffrey, standing at the front of the group, didn’t start yelling. His body language was coiled but his voice was calm. Yes, he was new to animated features, but he had quite a bit of movie-making experience and he was the head of production. And he was going to call the creative shots, whether some people in the feature animation department liked it or not.

But it wasn’t just animation that was changing. Jeffrey put new live-action comedies into production. They weren’t about anthropomorphic cars or field-goal kicking mules or alien felines, but properties more along the lines of Splash, one of the more adult comedies produced at the end of the Ron Miller era. The first into production was Down and Out in Beverly Hills, starring Bette Midler, Richard Dreyfuss and Nick Nolte, stars who were emphatically non-Disney but also not hugely expensive.

We figured out that Michael Eisner and Katzenberg were using a version of Walt’s old live-action strategy: make comedies with out-of-favor stars who don’t require a piece of the gross, and go with quirky, edgier stories. Only now, instead of Son of Flubber, it was Down and Out in Beverly Hills. (It was kind of a shock to see Nick Nolte coming out of the Disney commissary dirty and bearded. He played a homeless person in the picture, and believed in immersing himself in the role–not washing, hanging out with homeless people, a full-bore “method” approach.)

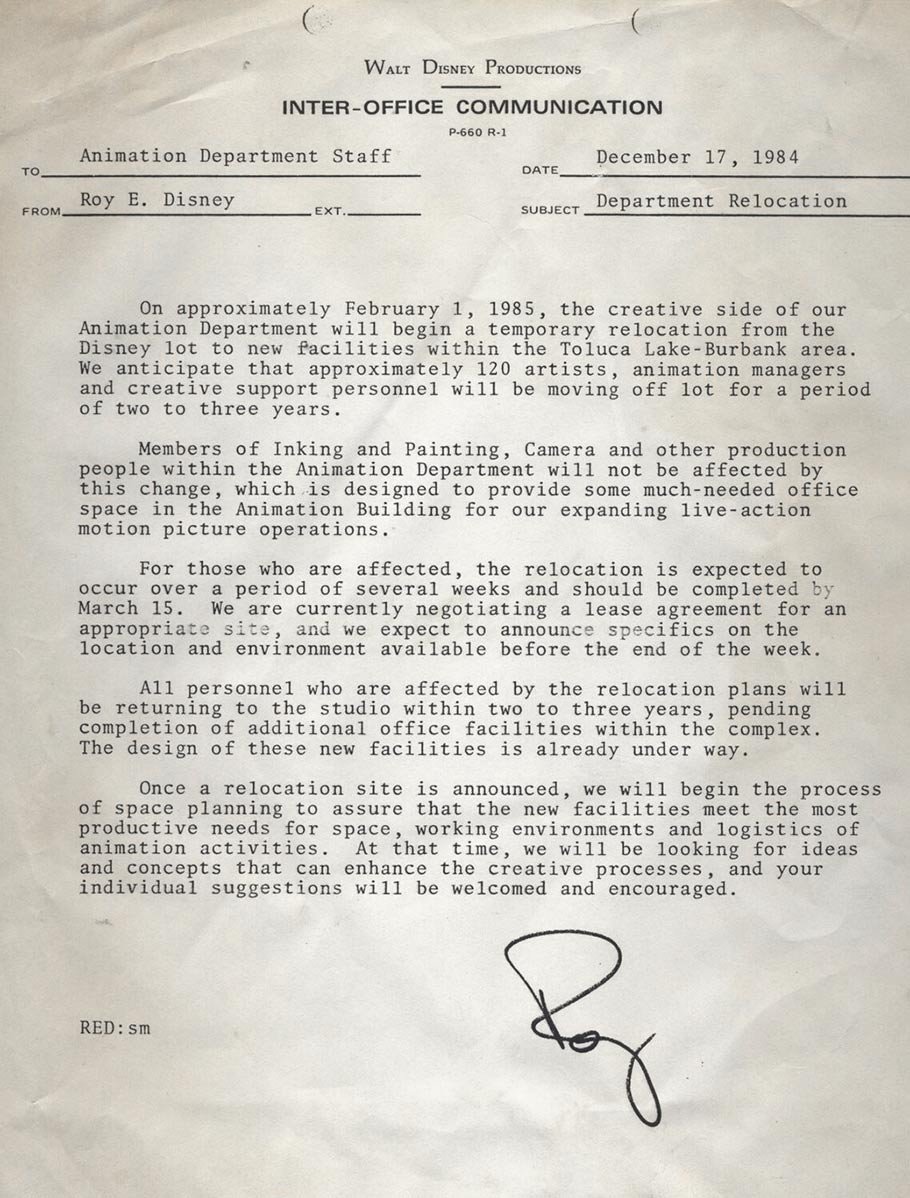

Changes kept coming. One afternoon Michael Eisner dropped down to the second floor story rooms. Leaning against a doorway, he mentioned that the animation department would be moving out of the animation building.

“We’re bursting at the seams around here, bringing in new people, starting new projects. We just won’t have room for you guys in this building,” he said.

Shock. John Musker asked where the department would be going. Michael waved a hand and shrugged.

“We’re not sure yet. Glendale, we think. But Glendale is only temporary. We’re going to build you guys a whole new headquarters on the lot.”

Artists were gathered around him, and a few of them nodded. Nobody was smiling. A new headquarters. So what was wrong with the old headquarters? Why didn’t management build a new structure for the herd of new execs that were streaming in and leave us in place?

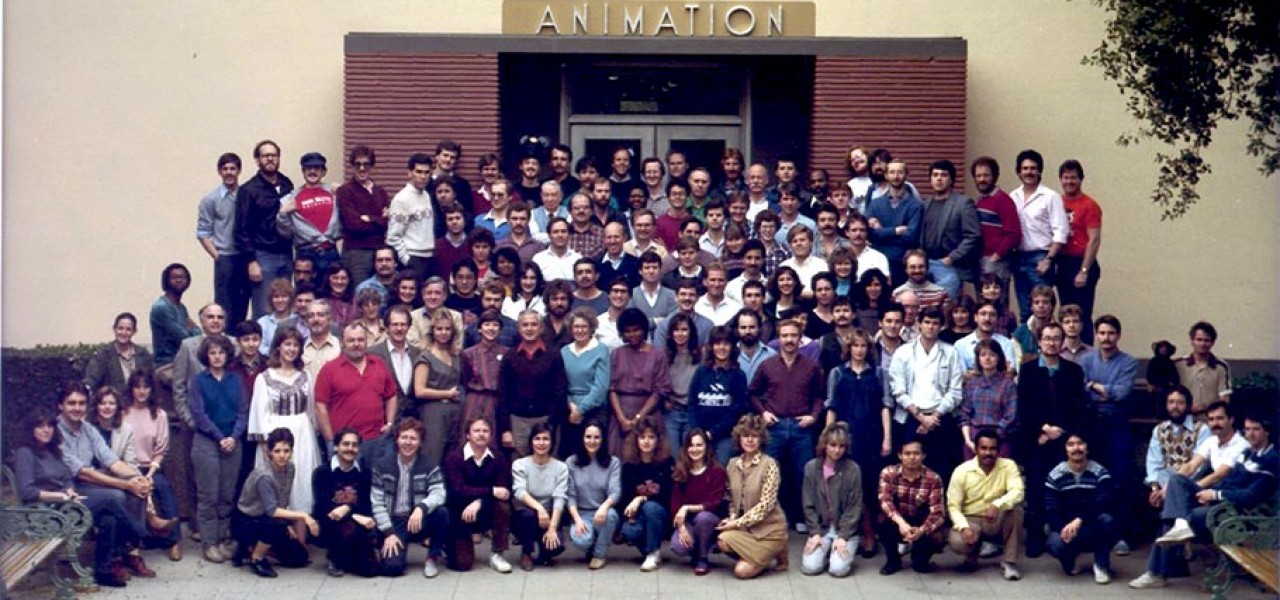

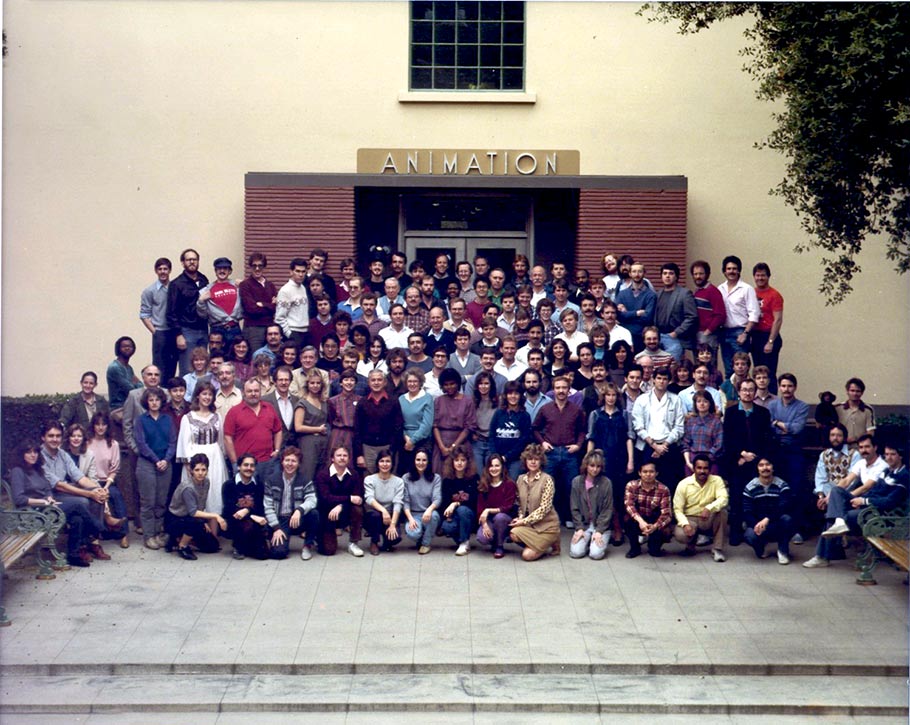

Word soon got around that we would be moving. The department gathered for a commemorative photograph outside the front entrance, but it didn’t do much to raise spirits. Memos were posted that drinking fountains in the building were inoperative due to plumbing renovations, so please use the new water dispensers.

Staff, naturally enough, bitched about the drinking fountains, which led animator Ed Gombert to see an opportunity for a practical joke. Bright and early the next morning, he posted official-looking memos on outside doors that said:

“Due to the ongoing plumbing work, all restrooms in the Animation Building will be closed until further notice. For convenience, Andy Gumps [portable restrooms] will be placed on each floor at the ends of the halls.”

Mr. Gombert, always happy to stir the corporate pot, sat on a bench near the Animation Building entrance and watched reactions of early arrivers. The first person into the building, a man in a suit, stared at the notice with gaping mouth. The man scowled sharply, then stormed inside.

The second person who stopped to read the memo duplicated the first’s reaction. So did the next three people who read it. Ed sat on his bench chortling quietly.

The notices were soon pulled down, and nobody fingered Ed as the culprit who had put them up. (This was not to be Ed’s only foray into fake memo writing. A year later, he would write a more elaborate specimen, but more on that later.)

A short while later, Disney management located a sprawling, one-story building in the industrial sector of Glendale, four miles from the studio. Over the course of weeks, layout, animation, design, and finally the story departments were moved to their new home located a block from the company’s WED subsidiary. The offices were dark, small, and utilitarian, and there were few restaurants within walking distance. But it was better than having the work out-sourced, better than sitting at home as a former Disney employee, hoping for the phone to ring.

At Paramount, Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg had used department-wide pitch meetings–called “Gong Shows” after the game show of the same name–to get ideas for film projects. The rejection rate was high, but the word went out that directors and story people in the animation department were going to have a gong show of their very own in a few weeks. Senior and junior employees were expected to attend, and everybody was told to have at least two ideas to sell. It was also made clear that management wanted to take animation in new directions. Moldy old fairy tales were out. Smart, modern stories for the twentieth century were in.

Nerves on edge, I haunted the studio library, searching for projects that would make Michael and Jeffrey green-light something and keep me around. I looked at dreaded fairy tales; I rooted through shelves of children’s books. I finally settled on a couple of Bill Peet books and the Rudyard Kipling story “The Man Who Would Be King,” and worked each up into short paragraphs.

Please God please God please God. Make these work make these work make these work.

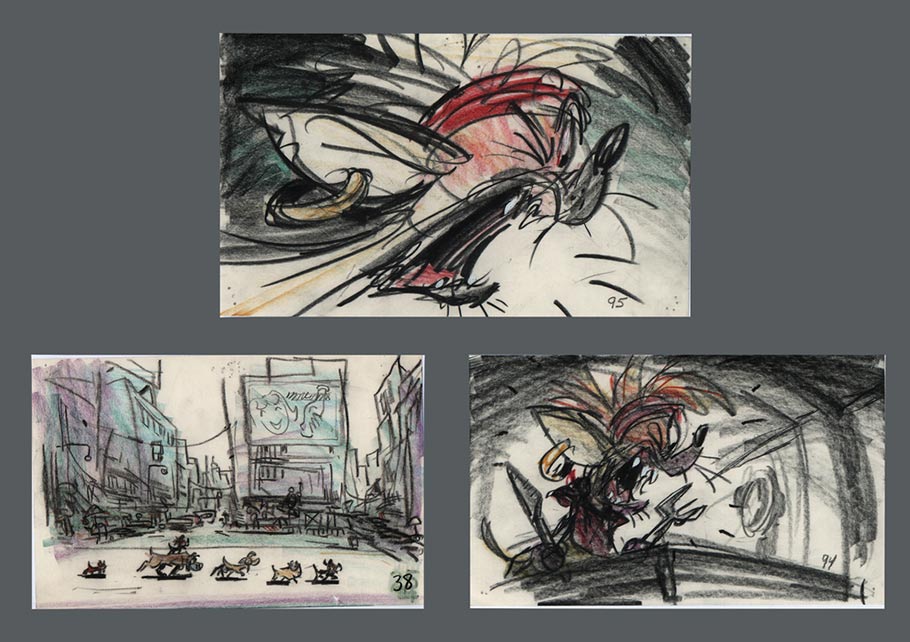

Pete Young, pretty much like always, came up with the solid idea of transforming Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist into a movie that replaced orphan boys with dogs and cats, led by the human low-life Fagin. As soon as he told me what he had in mind, I kicked myself: “Why the hell didn’t I think of that?”

The Eisner-Katzenberg pitch meeting took place around a big, rectangular table in a large room in the studio commissary. Michael E. and Jeffrey K. sat at the head of the table, and opened the proceedings by telling us how they had used big pitch sessions with great success at their previous studio. Michael (jocularly) took credit for Beverly Hills Cop. Jeffrey (jocularly) objected, saying he had pushed the film before Michael did. I wondered just how truly jocular the act was.

The two of them slowly worked their way around the table, listening to pitches. Jeffrey was cool to a director’s idea about “Hansel and Gretel” from a Valley Girl perspective. He didn’t like my Bill Peet pitches, but thought that “The Man Who Would be King” had possibilities, and asked to see a treatment. (“Hey now!” said my deluded inner voice. “I’m on my way!”)

Joe Hale proposed a couple of World War II themed features, and even brought funny small visuals, but Jeffrey and Michael said “Don’t think so.” Director Ron Clements offered Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid” and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, relocated to outer space. Both good ideas, I thought.

Jeffrey tapped his teeth. “We suggested to Star Trek producers that Treasure Island was a doable property, but they went in a different direction. I’m not sure Island makes a good animated feature. And Disney just made Splash. We don’t need more mermaid pictures.”

Ron nodded glumly, but Ron Clements was (and is) nothing if not tenacious. Undeterred, he sent a treatment for “The Little Mermaid” to Jeffrey Katzenberg. Almost immediately Jeffrey reversed course and green-lit “Mermaid” for development.

But inside that first pitch meeting, it was Pete Young who hit the home run. As soon as the Oliver idea was out of Pete’s mouth, Jeffrey leaned forward, nodding.

“Dogs. New York City. I like it. We’ve got a modern update of a proven classic. And there’s a nice twist with the dogs and the cat. Let’s get to work on this.”

Pete left the meeting elated. I was elated, too, because I had “The Man Who Would be King” to work on, plus Pete wanted me to partner with him on his new project. What could be better?

On that warm, summer afternoon in 1985, the two of us walked down Dopey Drive convinced there were golden days ahead…which only goes to show how wrong the expectations of two foggy-headed mortals can be.

Mouse in Transition has been released in paperback and e-book formats from Theme Park Press. In addition to Hulett’s on-going narrative, the book contains a foreword by Disney director John Musker, a half-dozen interviews with Disney old-timers, and biographical sketches of Disney animation staffers who worked at the studio in the 1970s and ’80s.

.png)