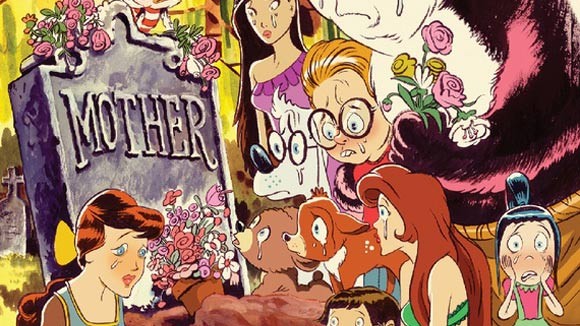

Know Your Feature Animation Cliches: The Dead Mother

On a few occasions over the years, people have asked me, Why do so many animated films have dead mothers in them? It’s something I’ve never had a good answer for; my general response is that it’s a time-tested dramatic device, and also, perhaps has something to do with the male-dominated culture of Hollywood screenwriting.

RELATED: Know Your Feature Animation Cliches: “This is Me” Opening Narration

The issue goes much deeper than that, however, and Sarah Boxer in The Atlantic has done a terrific job of untangling the history of the dead-mother plot and its comically overwhelming prevalence in contemporary American animated features. Just for starters, a few of the films that use this device: Chicken Little, Aladdin, The Fox and the Hound, Pocahontas, Beauty and the Beast, Kung Fu Panda, The Great Mouse Detective, Ratatouille, Brother Bear, Barnyard, Despicable Me, Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs, and most recently, Mr. Peabody and & Sherman.

Boxer’s provocative critique, “Why Are All the Cartoon Mothers Dead?,” is angry but spot-on. She makes a compelling argument that nowadays the plot device primarily advances the notion of the “good father”:

Take Finding Nemo (Disney/Pixar, 2003), the mother of all modern motherless movies. Before the title sequence, Nemo’s mother, Coral, is eaten by a barracuda, so Nemo’s father, Marlin, has to raise their kid alone. He starts out as an overprotective, humorless wreck, but in the course of the movie he faces down everything—whales, sharks, currents, surfer turtles, an amnesiac lady-fish, hungry seagulls—to save Nemo from the clutches of the evil stepmother-in-waiting Darla, a human monster-girl with hideous braces (vagina dentata, anyone?). Thus Marlin not only replaces the dead mother but becomes the dependable yet adventurous parent Nemo always wanted, one who can both hold him close and let him go. He is protector and playmate, comforter and buddy, mother and father.

In the parlance of Helen Gurley Brown, he has it all! He’s not only the perfect parent but a lovely catch, too. (Usually when a widowed father is shown onscreen mooning over his dead wife’s portrait or some other relic, it’s to establish not how wonderful she was but rather how wonderful he is.) To quote Emily Yoffe in The New York Times, writing about the perfection of the widowed father in Sleepless in Seattle, “He is charming, wry, sensitive, successful, handsome, a great father, and, most of all, he absolutely adores his wife. Oh, the perfect part? She’s dead.” Dad’s magic depends on Mom’s death. Boohoo, and then yay!

As usual in discussions about storytelling in American feature animation, the only contemporary filmmaker who emerges unscathed is Brad Bird, whose film The Incredibles is praised for being “not another desperate attempt to assert the inalienable rights of men, but an incredible world where everyone has rights and powers, even the mothers.”

.png)