Interview: Ralph Bakshi on the Animation Industry, Then & Now

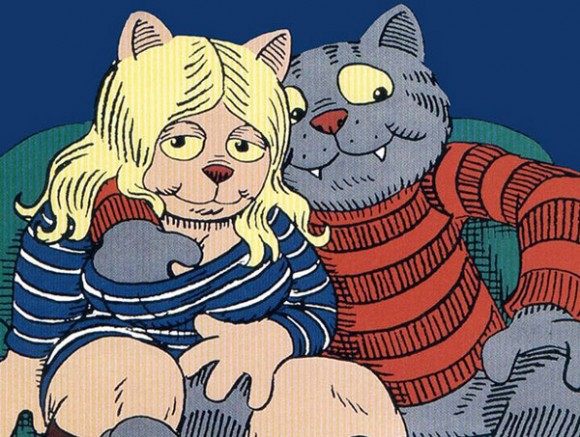

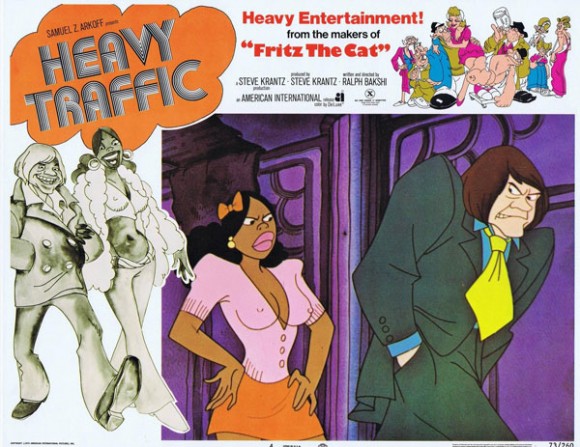

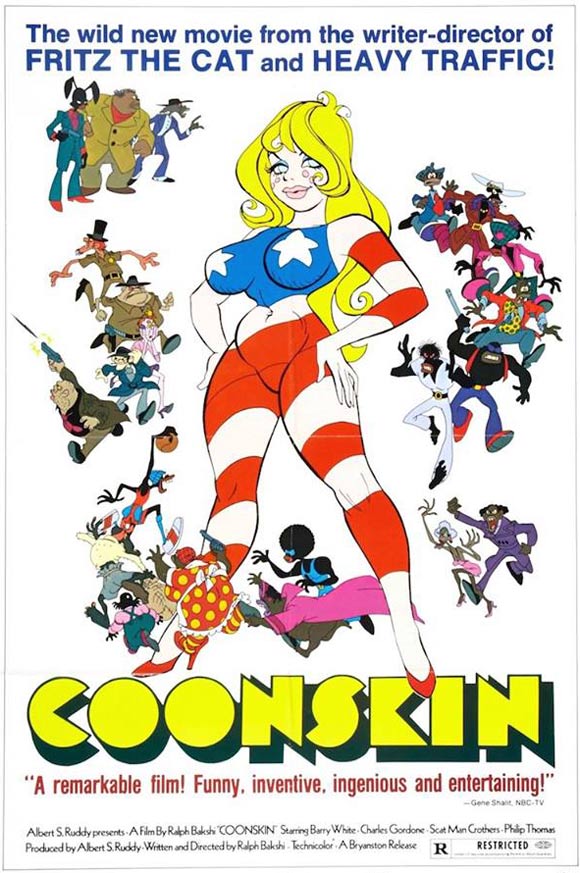

BAM Cinématek’s film retrospective Cool Worlds: The Animation of Ralph Bakshi begins this Friday in Brooklyn, New York. The tribute will run from May 9-20, screening a selection of Bakshi’s cult animated classics including the slacker sex comedy Fritz the Cat, the blaxploitative Coonskin and the autobiographical Heavy Traffic. In addition, Q&As will follow showings of Traffic and Coonskin on Friday and Saturday, May 9th and 10th, in which Bakshi will be in attendance.

BAM Cinématek’s film retrospective Cool Worlds: The Animation of Ralph Bakshi begins this Friday in Brooklyn, New York. The tribute will run from May 9-20, screening a selection of Bakshi’s cult animated classics including the slacker sex comedy Fritz the Cat, the blaxploitative Coonskin and the autobiographical Heavy Traffic. In addition, Q&As will follow showings of Traffic and Coonskin on Friday and Saturday, May 9th and 10th, in which Bakshi will be in attendance.

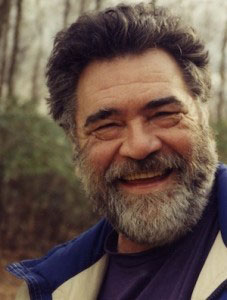

Mr. Bakshi pulled himself away from his drawing desk in New Mexico to chat with Cartoon Brew about his legacy, his latest project The Last Days of Coney Island, which he recently funded on Kickstarter, and what he really thinks about the computer’s role in animation these days.

Mr. Bakshi pulled himself away from his drawing desk in New Mexico to chat with Cartoon Brew about his legacy, his latest project The Last Days of Coney Island, which he recently funded on Kickstarter, and what he really thinks about the computer’s role in animation these days.

CARTOON BREW: I read somewhere recently that The Last Days of Coney Island will end a 20-year retirement for you. But does someone in your line of work ever really stop creating? Is there really such a thing as retiring?

RALPH BAKSHI: [Retiring] never happened to me, I have never stopped drawing a minute since I went into the High School of the Industrial Arts in the ’50s. I don’t really care whether I’m drawing cartoons for myself, or painting a picture or doing some big-ass animated feature for Warner Bros., it’s all the same to me. The thing that’s most important is drawing and learning how to draw better, or painting and learning how to paint better. So, how could an artist retire? I go to museums and I study a lot of art, it’s the only thing I know how to do. So, that’s what gets me up every morning and that’s why I’m still alive.

This thing about creating and being an artist and being a cartoonist is the most important thing we have: you, me, anyone else. There are other things more important, but that’s what we love. Now, how much money we make at it and how much we suffer is different for everybody, regardless of talent and that’s the way life is, it’s not fair. But if you [ever] give up drawing or painting or learning more about the arts, you’re hurting yourself because that’s all we really are.

Everything else is hype and ego; I could be famous or not famous. What’s most important for me is that the films that I bled for and fought everybody for are still playing, these films that are playing at BAM are 35-40 years old, and who is watching [them]? Young guys. Now when I made these films there were all these other features being made in the ’70s, by Disney and everyone else – they’re not playing anywhere. So, all these battles that I had to say an artist has a right to do whatever he wants seems to be coming out okay for me.

There is no retirement; you retire only if people have a hold on you, you know, studios. If you feel worthless because a studio hasn’t hired you then you’re kicking yourself in the ass as an artist. Studios hire you and you laugh and they pay you a lot of money, and if they don’t hire you, you’re still laughing but you’re drawing everyday and trying to get better. That’s not hype, that’s how I’ve lived.

CARTOON BREW: After all these years of young people discovering your films, have you ever been surprised by their reactions?

CARTOON BREW: After all these years of young people discovering your films, have you ever been surprised by their reactions?

RALPH BAKSHI: I have thousands and thousands of emails from every country in the world from young people who have run into my films and send me the most laudatory stuff. And they all virtually say the same thing, that the films are still relevant, that they’re still saying stuff. Generation after generation, I’ve heard from hundreds of thousands of people worldwide, they find it by accident, they find it on Youtube, they find it because somebody told them, and then they have to react to it.

No one’s ever said, like in the old days: “We want you to quit animation. We hate you. You’re terrible for the business,” no one’s ever said that. I’m sure there’s some people who hate it, but what I’m saying is the reaction I get from young people has allowed me to work as hard as I’m working now. Those things give you courage; they give you a feeling of you didn’t fail. I left the business pretty beat up, I left the business exhausted and tired. Those films were exhaustingly hard to make with low budgets. The studio fights were very difficult, the cutting down my films [was] very difficult. I left pretty much a basket case. But this is why I left, I couldn’t go on anymore. But slowly from my own place at home, I recouped.

CARTOON BREW: I don’t think a lot of people realize how much more difficult it was to make an animated feature forty years ago than it is today…

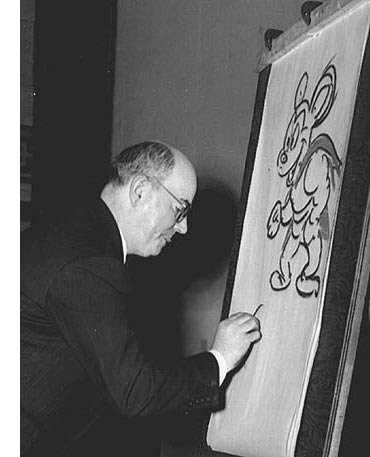

RALPH BAKSHI: I was Jim Tyer’s assistant, and before I was his assistant, I was his inker. I had to ink his scenes with crow quill pens on cels, and he did every drawing. Well, Jim [was] a brilliant, brilliant, wonderful cartoonist. He used to tell me, “Hey Ralph, everything moves. Don’t worry about it.” And I carried that my whole life. If it wasn’t for Jim, I wouldn’t have been able to make Fritz the Cat. I didn’t have any money, I had under a million dollars and in those days, you needed fifteen to make a feature. [If] you didn’t have fifteen million dollars, don’t even start, it’s impossible. But I started because Jim told me, “Everything Moves, don’t worry about it. Everything moves”.

At Terrytoons, we couldn’t even afford to animate with pencil tests. I grew up learning how to animate by just animating and then looking at it when we saw the finish. Now that’s unheard of, but that’s how we did it, every one of us did it. So, we didn’t have any pencil tests on Fritz and Traffic and Coonskin, I storyboarded, timed it with a stopwatch and wasn’t too concerned about pencil tests, you kind of get a feeling if it’s working or not from flipping [scenes] and then you pass it to ink and paint. Every animator I worked with [on Fritz the Cat] was so professional—Johnnie Gent, Rod Scribner, Virgil Ross, Manny Perez, Jim Tyer—well, I’m not going to worry about them knowing how to animate. Sure I would have liked to have done some stuff over, but I hate if you get too polished with a scene. Art, to me, [is] about looseness, bad voice tracks, fuzzy photographs, bad color, I have this whole thing about loving the underbelly of animation, and that’s what I keep pushing. I mean, The Last Days of Coney Island, I don’t have a slick line around the characters. I’m just continuing to push the way I see animation and that’s not because everyone else is doing it wrong, that’s not because everyone else isn’t great. I’ve never seen so much great art and designers and computer work in my whole life. It’s amazing what the kids today are doing.

CARTOON BREW: With all the access to animation resources today, do you feel that maybe younger animators are focusing more on studying the resources, but not necessarily applying the information to their work?

RALPH BAKSHI: Don’t forget I’m coming back to what I think art should be. That’s why I love Jackson Pollock, who’s so expressionistic; Chaim Soutine, who was extraordinarily twisted and who was killed by the Nazis; and Francis Bacon, the great English painter. You look at these guys; they’re not looking at books on the art of anatomy, and all this stuff, they’re coming from their gut and their heart.

Now, if you try too hard, if you go pose-to-pose – here’s where I get into real trouble – if you go pose-to-pose and you do perfect posing and you’re really telling the characters where to go and this is what you do, “This is how the foot lifts on the crossover,” it gets too tight, too manneristic. I love straight ahead animation; I love accidents. I learned as much as I could as a kid and then when I started to do it as a young man, I found myself tripping over myself. I kept running over to a 16mm and running it down by hand to see how many drawings Chuck Jones used in a Road Runner cartoon, but that’s what the books told me to do, and though I looked at all those Disney books on animation and all those guys… you see how hard they worked to get a pose, how many thoughts they had about attitudes and silhouettes and all this stuff and my work started to drain; it was all someone else’s work, or someone else’s thoughts. I never was able to produce an action that didn’t look fucking ridiculous!

Jim Tyer broke me out of all that garbage; he had the most fun I had ever seen in my life for an artist. Because we had no air conditioner at Terrytoons, he’d sit there animating in his underwear; he’d have this stack of drawings on his desk. Blank. Next to him was an exposure sheet, everything was exposed on 2’s, nothing was drawn, but he’d start at the top: 1, 2, 3, everything on 2’s right down to the 10 feet he was animating. I said, “Jim, how could you be exposing if you’ve got no drawings?” He’d laugh, he’d smoke a cigar and he started to draw. I’m sitting there on a wastebasket watching him, okay. He’d draw a nose on one page, with an eye. One. He’d turn back a page and he’d draw another nose, same nose, same character, with an eye. Flip it. He works on the entire fifteen or twenty pages. Drawing one eye at a time. Flipping them. And the magic started. It started to wiggle, it started to shake, started to bend – and he’s laughing. He’s enjoying himself while the other guys are sitting there cursing and sweating trying to make the perfect Milt Kahl pose!

I learned what animation was on a whole other level. I learned that you just do what you feel and you have a ball because you’re a cartoonist, you’re not Norman Rockwell. Jim taught me not to be afraid, Jim taught me that mistakes were okay. “You’re just doing a fucking animated scene, it ain’t the end of the world. I’m working for Terrytoons, that ain’t the end of the world.” All this I carried with me, so when it came to making animated features for under a million that weren’t perfect in animation, I shrugged. You know, a guy used to scream at me at using rotoscope on Lord of the Rings and along came the computer and everything is motion control. [Motion control] has made a lot of companies very happy and Ralph Bakshi caught all kinds of hell for rotoscoping. Because I got so goddamned tired of animating for under a million dollars, I was just burnt out.

CARTOON BREW: What do you think of modern animation with low budgets and low production values? Like on Adult Swim?

CARTOON BREW: What do you think of modern animation with low budgets and low production values? Like on Adult Swim?

RALPH BAKSHI: I’m out of touch, I don’t watch television anymore. I can’t really answer to what the kids are doing. I know that what I’ve seen, here and there and especially from computer animation feature films. It’s mind boggling! I’ve seen effects that you couldn’t even dream about doing it in my day.

Now, I have a belief that every artist has a sense to what makes his animation work. There are all kinds of artistic sensibilities in my studies that went into [my work], I might not care, but I’m making choices off of a lot of knowledge. I’m not making choices as some naïve idiot. I’ve studied painting, I’ve studied photography, I studied all the old Warners, I studied all of the old Terrys, I loved Max Fleischer – the black and white Popeyes. There is a lot of information that I’m making these decisions with and don’t think I don’t change stuff and don’t think I don’t reanimate stuff and don’t think I don’t throw animation that I’ve done out. If it don’t work for me, it goes in the garbage. So all I’m going to say is that none of this stuff that I talk brazenly about, none of it just happens without tremendous amount of studying.

But you have to understand, my theories came out when animation was dying, everyone is part of their time, you can’t get out of it. All of my moves and all my theories came out when animation was dying. Falling dead. No one cared. That’s where all these things started with me, that’s my life. I don’t know what would have happened to me if I came into the business today and Pixar only gave me five grand to sit there doing dumb storyboards. I came from Terrytoons collapsing, Paramount closing, Warners closing. I came from a different mindset.

So… I don’t know what the guys are doing, what I’ve seen in glimpses is the most amazing artwork I’ve ever seen in my life. Films and drawings and effects and the industry’s making a fortune, so I guess things are fine.

CARTOON BREW: Your work has always had a strong racial component. It’s different climate now, black President, black Disney princess, etc. But for a long time, if you saw a black animated character, chances were it was in one of your films. What was the responsibility you felt to explore racial politics in your stories?

RALPH BAKSHI: I’ve always felt a responsibility to finding out how I felt about certain issues. I felt a responsibility to discuss issues with myself as a writer on things that I was unsure about. On Coonskin, I read every Uncle Remus tale I could find, I read every black history book I could find, I read [about] black music and black culture. I wanted to find out everything I could about these people I was animating, and I had certain opinions. You know there were black revolutionaries in the ’60s and ’70s when I was growing up, some were very much for Martin Luther King and what he was trying to do with integration, and a whole bunch of others were just making money. One guy said to me, he worked in animation, he was a cameraman, and he would say to me, “Hey Ralph, I went to Harlem and I opened up a revolutionary church and they just packing me in with money and the government is giving me all this money to support, y’know” and of course, it’s going in his pocket, and that turned into Simple Savior in Coonskin.

What I’m saying is, a writer should write about what he knows and what he understands, and I grew up in a very integrated neighborhood, Brownsville, Brooklyn, it’s Jewish, Puerto Rican, Black, Italian. I grew up with people that were amazingly interesting to me, and that’s what I knew and that’s what I love so, I started to write animation about these people and their lives. That’s where it all started.

Did I have a responsibility to discuss issues? Absolutely. Bobby Dylan was discussing issues – Disney wasn’t. And look at Coonskin, all the issues I’m discussing, Miss America lynching people, et cetera. Those were all out of issues that were happening at the time, without trying to make fun of that stuff.

So yeah, I always felt a responsibility to discuss life. Why animate otherwise? It’s too much work to just entertain somebody, it’s ridiculous! I mean, if you want to entertain people, well there’s lots of ways to entertain, sometimes you got to yell at them.

CARTOON BREW: One of the most memorable things, for me, in the book Unfiltered: The Complete Ralph Bakshi, was its mentioning of how much you influenced and supported John Kricfalusi. I’ve always been fascinated when an artist is influenced by other artists, because they can create something entirely new through their admiration of someone else’s work.

CARTOON BREW: One of the most memorable things, for me, in the book Unfiltered: The Complete Ralph Bakshi, was its mentioning of how much you influenced and supported John Kricfalusi. I’ve always been fascinated when an artist is influenced by other artists, because they can create something entirely new through their admiration of someone else’s work.

RALPH BAKSHI: Absolutely! I built on Fleischer and Jim Tyer, and, like I said earlier, everything I did was coming out of a lot of knowledge. What you got to be careful about is not to build it exactly on top of those people, [because] then you look like those people. That kills you, so use that knowledge and then create something new. So much of this stuff looks alike because of that, but those are fine lines – art is such a tricky thing – those are fine lines, those are choices.

What I’m not trying to do is copy anyone else, what I’m not trying to do is be Bob Clampett, I’m not trying to be Max Fleischer, or Jim Tyer, or Milt Kahl or Ollie Johnston. I’m just trying to be me with all of the knowledge those guys taught me, that’s what’s important to me: being yourself.

John happened to be a very incredible talent, tremendous sense of humor, and tremendous drawing ability. He was very rare. I made him a director because I thought he was that talented, because he was, and still is. But I’ve never seen so many people copy [anyone] in my whole life. I love John K because he’s an original, but I don’t want to see a watered down John K. I think those guys are very great talents, but I’m not a great fan of artists getting lost in someone else’s style because they think it’s commercial. It’s a hard choice, you’ve got to learn from the masters and work just as hard to go the other direction. We have to move on, hopefully I’ve moved on in Last Days.

CARTOON BREW: How far along is Last Days?

CARTOON BREW: How far along is Last Days?

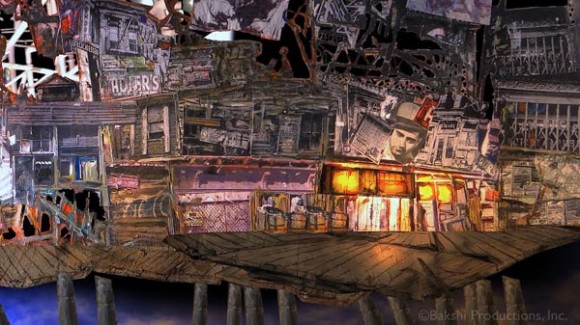

RALPH BAKSHI: Well, we’re getting there, I would say I’m 70% finished with the film. First, we went up on Kickstarter for a six minute budget, right? I got it. My picture is now eighteen minutes long, with the same six-minute budget, but [I’m animating] everything myself and not paying myself, so the eighteen minutes don’t bother me. I’m also doing all of the backgrounds. I’m painting them and collaging them. You can see them on Facebook. This is going to look different so I’m happy. I’d like to finish it as a feature. The eighteen minutes that we do is certainly a pilot and people can judge if this picture has any legs or not. Now, I’m trying to con people into painting the cels very cheaply.

CARTOON BREW: And is that working for you?

RALPH BAKSHI: Yeah, it’s working for me. Because they make decent money, because they go so fast on the computer. Everyone’s doing fine.

CARTOON BREW: Isn’t it amazing how much can be done these days with one good computer?

RALPH BAKSHI: The computer is the greatest single instrument that ever happened to an animator. The computer is such a magical thing. Yeah, I’m animating again, and I’m calling for shadows under the characters feet and I’m calling for different colored ink lines and having some machine ink it so fucking fast you can’t believe. I’m adding live action; I’m doing all the things in my library with one editor that used to cost me hundreds of thousands of dollars in my studio. And I’m pencil testing everything I do for the first time in my life. I can’t tell you how stunning the whole situation is for animators. Let me say something, if Heavy Traffic cost a million dollars in its day, which it did, I could do Heavy Traffic today on the computer, for two hundred thousand dollars. The computer is god. [Laughs]

For more information on Ralph Bakshi and The Last Days of Coney Island visit his official Facebook and Vimeo pages.

.png)