Mamoru Hosoda On ‘Scarlet’s’ Shakespearean Roots And Developing A New Hybrid Pipeline

While anime may be a major blind spot for Western awards voters, Mamoru Hosoda’s latest animated feature, Scarlet, has a pedigree that they likely can’t ignore. Distributed by Sony Pictures Classics and inspired by Shakespeare’s Hamlet, it’s a blend of prestige arthouse storytelling with top-notch anime visuals.

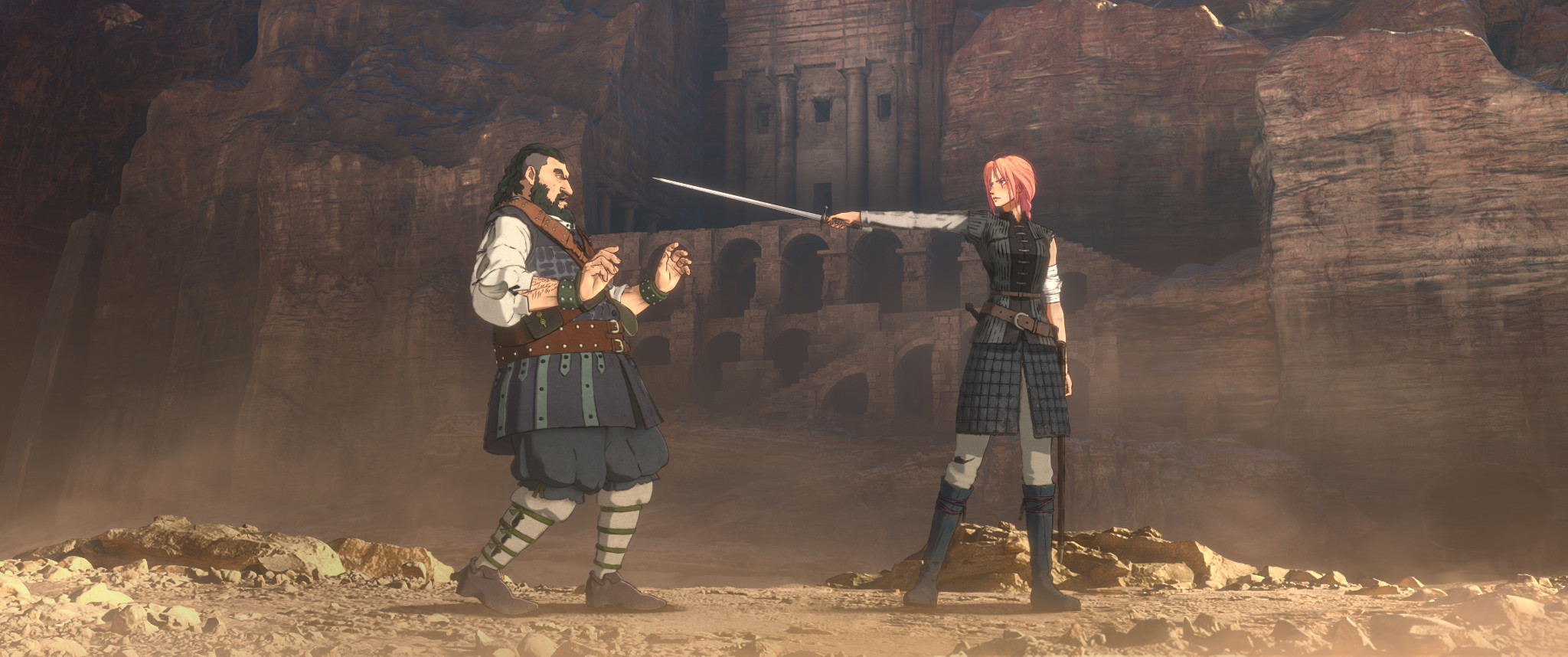

The film follows the time-bending adventures of Scarlet (Mana Ashida), a medieval-era princess who is pursuing her villainous uncle Claudius (Koji Yakusho) to avenge the murder of her war-hero father, King Cornelius (Yutaka Matsushige).

Hosoda uses Scarlet to explore the bitter cycle of vengeance, forgiveness, and the power of compassion. The film’s protagonist travels from her origin in 16th-century Elsinore to the wasteland of the Otherworld, where she meets a modern-day nurse who helps heal her broken heart through connection and caring. Hosoda and his animators at Studio Chizu collaborate with CG artists at Digital Frontier to merge their talents and create a breathtaking hybrid landscape.

Cartoon Brew sat down with Hosoda-san and translator Mikey McNamara in Hollywood to discuss the director’s evolution as an animator, his ambition to push Japanese animation into new areas of technique, and the timelessness of adapting Shakespeare for new generations. Scarlet opens in IMAX theaters on February 6, 2026, and nationwide on February 13, 2026.

Cartoon Brew: Once you finished Belle and were thinking about what the studio was set up to do next, what kind of preparation was needed for the idea and its execution as you developed Scarlet?

Mamoru Hosoda: Speaking of the order that everything kind of fell into place, first, I wanted to tell a revenge story, so that was already set. One of the original revenge stories, of course, is Hamlet, which takes place in 16th-century Denmark. And naturally, you’re going to need royalty, so the main character is a princess.

We knew the scale or scope of the production was going to be bigger, but so was the story and the background. In my past films, I tended to deal with more intimate stories, characters you might find in everyday life, like a high school student or a young boy. When working with a princess, and eventually a queen, as the main character, there are going to be events that affect the course of history. That’s what royalty is about.

I felt the visual expression needed to be elevated to match the scale of the story and its themes, which naturally translated to a bigger budget as well.

As you were making Scarlet and seeing stylistic changes in animation, like Arcane or the Spider-Verse films, did work by your peers influence how you handled 2D and 3D in this film?

When I was promoting my last film, Belle, I had the opportunity to visit Studio Fortiche, which did Arcane, in Paris. They were doing a lot of innovative visual expression. Before the second Spider-Verse was released, I also had the opportunity to visit Sony Animation Studios and tour the facility right before the film came out. I got to see some of what they were doing as well, and I remember being very astonished.

Rather than directly affecting me, it was more of a stimulant, thinking, “Wow, I need to do something as well.”

More than the American or international public might realize, Japan is very rooted in 2D, hand-drawn animation, almost to a fault, with an artisanal approach to how we breathe life into characters. It can feel like there’s an opposition between 2D animation and 3D animation, but I think that opposition is nonsense. Animation is simply a means to deliver something on screen, so why not take the best of both worlds? That was the starting point for the visual expression in Scarlet.

I wanted to pay respect to the history of Japanese 2D animation, but also expand the possibilities and horizons of what we can do with it. I see what I did with Scarlet as an update—not a revolution or a reset. Similar to how Arcane and Spider-Verse define their own unique styles, I wanted to find a new way for Japan to use CG while retaining the visual charm that makes hand-drawn animation unique.

The prologue of Scarlet gives audiences a very effective primer for what they’re about to see. Was it always structured that way?

With regard to the different animation styles, 2D hand-drawn and 3D, I did something similar in Scarlet to what I did in Belle, where I separated worlds by technique. In Scarlet, when we see Scarlet in 16th-century Denmark, it’s all cel-based, hand-drawn animation. When she’s transported to the Otherworld, it becomes CG.

I knew I wanted to develop a new look to match the gravity of the themes and story of the Otherworld. Initially, I thought it would be more different. Because the 2D and 3D pipelines were so different, it had the potential to diverge much more. In the end, the styles ended up closer than I expected, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

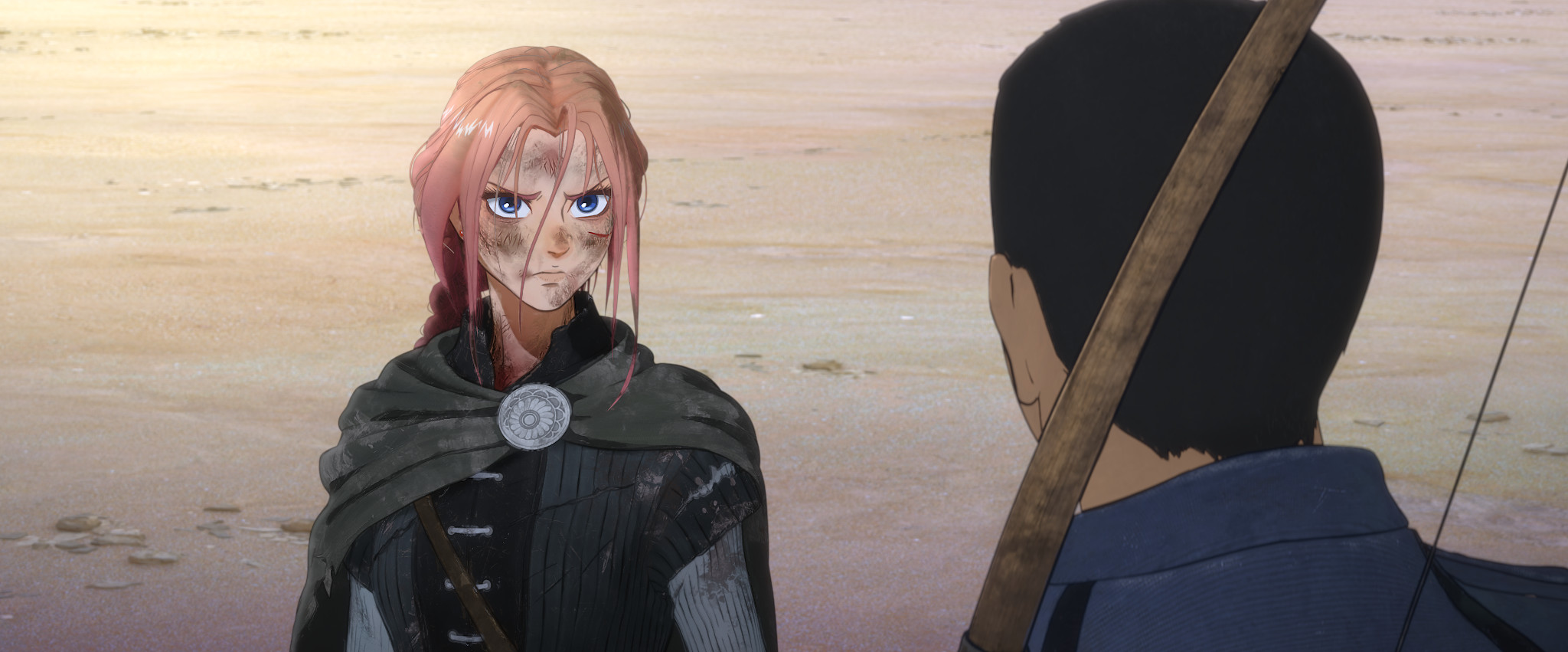

With the 3D style, I wanted to build on the history and learnings of 2D expression, but add another emotional layer by taking advantage of what can only be done in 3D. For example, the grit and dirt on Scarlet’s skin and face would be very hard to do in 2D, but in 3D, textures make that possible. Likewise, details like her chapped, messy lips were elements we fully leaned into. In the end, there’s a unified tone, manner, and mood across both worlds.

Was there a need to bring in new talent or technology to achieve what you envisioned for Scarlet?

To give some context on how Studio Chizu works, we’ve traditionally been a hand-drawn animation studio. Our use of 3D goes back to Summer Wars in 2009, when we collaborated with a CG studio called Digital Frontier. They’re more rooted in video games and CG for live-action films, and in many ways, we’ve grown together.

In Summer Wars, about 10 to 20 percent of the film was CG. By Belle, it was about 50/50. In Scarlet, it’s closer to 80/20, CG to hand-drawn. As Studio Chizu and Digital Frontier evolved together, we developed a much deeper understanding of how to collaborate.

In addition, the character design for Scarlet and Hijiri was done by Jin Kim, who designed characters for Frozen and Big Hero 6 at Disney. He has a strong background in 2D animation, but designs characters that translate very well into 3D models. His role was essential in establishing the new look of the film.

Among the many ambitious sequences in Scarlet, was there one you spent the most time iterating on?

One of the most challenging scenes is when the two armies fight over the wall, and Scarlet’s army smashes through and climbs toward what you might call heaven. There’s the technical challenge of animating huge crowds—almost like a Ben-Hur scenario.

But even more challenging was the social relevance of the scene. People fighting over a wall is very resonant right now. When I first wrote it, I had no idea how current events would unfold. The geopolitical climate made it harder, because I wanted to present something truthful that would evoke an emotional response. That responsibility made it one of the most difficult scenes to tackle.

The sequence with Claudius after Scarlet ascends is quiet and intimate. How did the earlier large-scale moments impact that scene?

In Act 3 of Hamlet, when Hamlet is about to strike Claudius, there’s a huge inner struggle. I wanted to think about what Scarlet would do in that same context. In Hamlet, the ghost of Hamlet’s father demands revenge. In Scarlet, her father urges forgiveness, which creates an entirely different conflict.

The massive mob scene before that shows humanity from a bird’s-eye view, while the confrontation with Claudius is deeply personal. They’re the same theme expressed in two different ways—how we behave as a collective, and how an individual struggles internally.

Which moment in the film moved you the most?

Watching Scarlet’s journey as a whole was one of my proudest moments. In the beginning, she’s obsessed with revenge and is almost frightening. By the end, she’s crying like a child, regaining innocence and becoming someone worthy of leading her people. Showing that transformation through CG and animation was incredibly meaningful to me.

Because this is based on Hamlet, the hurdle was very high. But that’s what fascinates me about classical literature—what has stayed the same over 400 years, and what has changed. As a team, we felt we collectively achieved something new, and that’s one of my proudest takeaways.

Having transitioned to more CG than 2D in Scarlet, where do you see yourself going next as a storyteller?

It depends on the story. Scarlet hasn’t opened yet, but assuming audiences embrace it, I’d like to take on a new challenge, perhaps a different kind of story or scale that hasn’t been done in animation before.

When you think about how Hamlet was originally performed, with actors on a stage, creating profound emotion and nuance, I wonder if animation can reach that same level. That’s the next stage I want to explore.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

.png)