‘What We Create Gives Balance To The Industry’: Producer And Studio 4°C Co-Founder Eiko Tanaka On Maintaining The Company’s Creative Spirit

The animation of Studio 4°C has been pushing visual boundaries for decades. The studio was co‑founded in 1986 by producer Eiko Tanaka and animator Koji Morimoto (whose work outside of 4°C includes serving as animation director on Akira), and from its start, the studio has continued to prioritize idiosyncrasy.

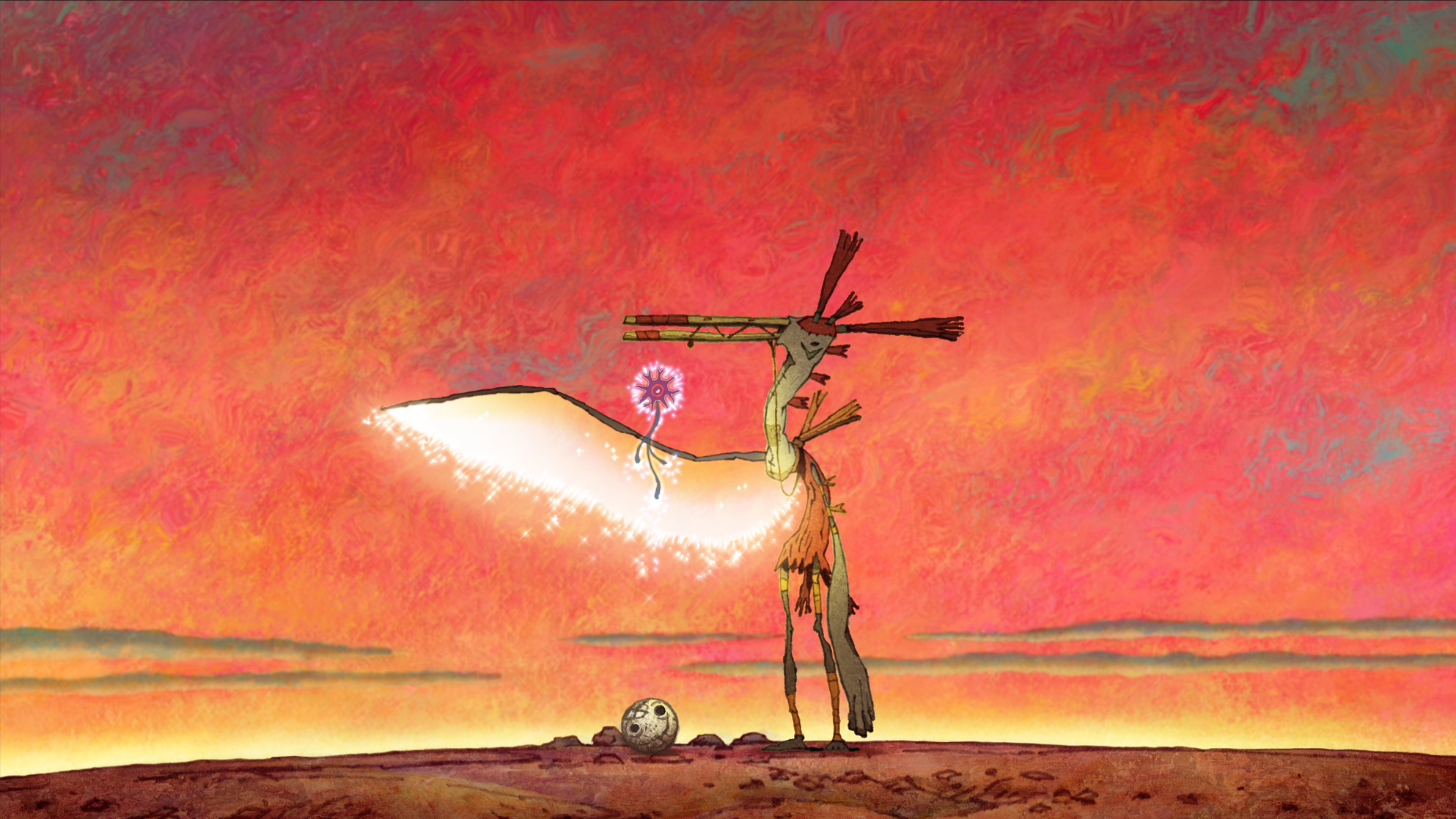

From the multimedia onslaught of Masaaki Yuasa’s Mind Game and the distinctive linework of Tekkonkinkreet, to the dreamlike haze of Children of the Sea (and its follow‑up, Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko), and more recent releases such as ChaO and All You Need Is Kill, few production houses can boast a comparable range of styles.

At the Scotland Loves Anime festival, Cartoon Brew spoke with studio co‑founder and producer Eiko Tanaka about how Studio 4°C works to keep that sense of originality alive.

Cartoon Brew: You once said in an interview with the publication FPS that the reason for Studio 4°C’s success is that it is not a “profit‑seeking company,” and that films are made by creators, not capital. What is it like trying to keep that creative spirit alive in the current anime industry landscape?

Eiko Tanaka: Especially in the Japanese animation industry, broadly speaking, there are two types of animation: work that aims for commercial success, and work that is more interested in cultural success. For a long time, Studio 4°C has focused mainly on films and on developing creativity, which means that we have been involved in broadening the cultural side of animation.

In the last few years, the Japanese animation industry has seen a great deal of commercial success. It has been invited to participate in fan events around the world and has produced many hit titles. Sales originating from the Japanese industry are now close to four trillion yen.

But as a studio that is focused more on the cultural side, we have not really seen those kinds of commercial benefits [laughs].

Personally, I feel that the kind of recognition we receive at film festivals in other countries needs to be fed back into Japan and turned into a sustainable way of making money.

Anime that tends to achieve commercial success in Japan is often based on manga. The kind of work that we create—the creativity we prioritize—helps provide balance. If it were not for studios like ours, everything would be manga‑based. In that sense, what we create gives balance to the industry, and the industry needs that.

With that focus on the cultural side of the anime industry, how has the growth of the studio affected how you pursue those goals? In that same interview, from 2008, you mentioned the need to scale up for a larger number of productions.

There are different ways of scaling up. You can scale up by bringing in different types of creators, by taking on more projects, or by making more money. For us, it is about the quality of the work and getting better at making animation that allows creators to express their talent. That is what scaling up means for us.

That brings me to different forms of expression. One of your current projects in cinemas, All You Need Is Kill, is fully CG‑animated. CG has been part of Studio 4°C’s work since Memories and Tekkonkinkreet. How do you view the studio’s approach to blending CG and hand‑drawn animation, and has that changed over time?

We made our first full 3DCG animation with Berserk, and then again with Poupelle of Chimney Town. Our latest is All You Need Is Kill. For us, CG is simply another tool. Even if we are not using pencil and paper, we are still creating 2D‑like, Japanese‑style limited animation. Whether we use a pencil or CG is just a different method of achieving something that, in the end, does not look all that different.

Now that 2D drawings can be made digitally, it is much easier to synthesize 3D and 2D. In the early days, combining paper drawings with digital animation was very difficult. I think in the future there will be even more mixing of 3D and 2D animation.

Studio 4°C has worked with a number of pre‑existing IPs in collaboration with foreign companies. How do you approach the balance between original projects and work based on existing properties?

What all of the projects we work on have in common is the passion and enthusiasm of the people I put in charge of them. That is not just the director, but also the art director, the music director, and the animation director. An animation project brings together many people, and everyone involved needs to love the title and want to work on it. In that sense, it makes no difference whether the project is based on existing IP or is completely original.

On the other hand, there may be projects that look interesting to me, but if no one has the passion to make them, we will not do them.

And when it comes to adapting manga specifically?

A lot of anime based on manga today tries to be as faithful as possible to the original work, in order to understand the manga artist’s intentions and satisfy fans of the source material. I understand that approach. But when we adapt manga at Studio 4°C, we focus more on what the director and the team want to express through the manga, rather than being 100 percent faithful.

When we adapt a manga, I always tell the manga artist that what we create will be different from the original, depending on what the director wants to do. We only proceed if the artist is comfortable with that.

Foreign interest in anime has grown significantly, along with the rise of streamers such as Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, Disney+, and anime‑focused platforms like Crunchyroll. Since Studio 4°C is largely focused on feature films, how have these changes affected the studio’s work?

For Studio 4°C, making films for theatrical release is very important. Even when we work with a streamer, we try, as much as possible, to ensure that the film is shown in cinemas. We made Hi no Tori (Phoenix: Eden 17) with Disney+, and we had to change various elements, such as the endings and titles. We created both a feature‑length film version and a four‑episode streaming version.

This approach takes more time and costs more money, but we try to adjust the work depending on the release format. We think carefully about how a project should change based on the medium.

You have spoken about how emphasizing the director’s point of view is central to Studio 4°C, something that drove the anthology Genius Party. Will we ever see another Genius Party?

Maybe, maybe not. At the time, there were very few opportunities for creators to express originality in feature films. Only one or two animated feature films were released in Japan each year, and there was neither the time nor the money to create those opportunities.

I wanted to provide that space. But now there are many more ways for creators to express themselves: music videos, opening and ending sequences, short films, and more. There are far more opportunities today, so I do not feel the same need to create that platform myself.

Finally, how do you feel Studio 4°C has changed since you founded it, if at all?

We have always expressed ourselves through animation. Even when animation was seen mainly as something for children, we made films for adults. What has really changed is the industry around us. Animation is no longer considered “just for children,” and it receives more media attention. Greater audience attention also means more money flowing into the industry.

Everything around us has changed, but I do not feel that we need to change ourselves in response.

Pictured at top: Ming Game, Genius Party, ChaO, All You Need is Kill

.png)