Cult Anime Legend Takeshi Koike Reflects On The Legacy Of ‘Lupin III’ And ‘Redline’: ‘The Key Word For Me Is Dynamism’

Director, animator, and character designer Takeshi Koike is best known in the West for his cult-classic directorial debut, Redline (2009) — an anime adrenaline rush of a racing film where you feel every swerve, acceleration, and expletive.

Over the past decade, Koike has also helmed a series of installments in the celebrated Lupin III franchise — a lineage previously shaped by such esteemed filmmakers as Hayao Miyazaki (The Castle of Cagliostro) and Seijun Suzuki (Legend of the Gold of Babylon).

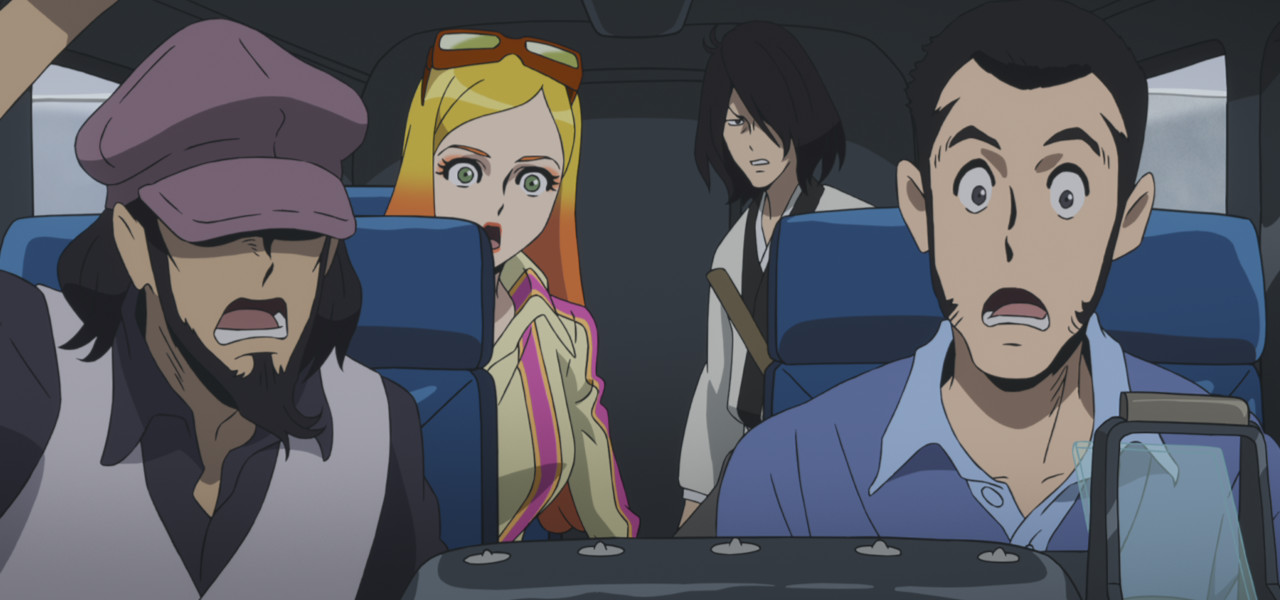

Koike’s first adventure with Lupin and company was as character designer and animation director on the spin-off series The Woman Named Fujiko Mine (2012), a radical reinvention that shifted focus to Lupin’s famed femme fatale. Following that series’ success, he took the reins for a run of mid-length and feature-length continuations: Jigen’s Gravestone (2014), Goemon’s Blood Spray (2017), Fujiko’s Lie (2019), Zenigata and the Two Lupins (2025), and now The Immortal Bloodline, which concludes Koike’s long-running Lupin arc and ties up its remaining threads. It’s the first fully 2D-animated feature-length entry in the franchise in nearly thirty years.

Cartoon Brew sat down with Koike on the eve of the UK premiere of The Immortal Bloodline to discuss saying goodbye to Lupin, the collaborations at the heart of his work, and the driving energy behind his gonzo storytelling and dynamic action.

Cartoon Brew: You’re best known in the West for Redline, of course, but I want to start by talking about Lupin III. What strikes me about both your entries and others in the series is that Lupin films are effortlessly “cool.” What, to you, is cool about Lupin?

Takeshi Koike: I think it’s his daredevil nature — the way he’s so positive about everything. He moves in an underworld that we don’t see in our day-to-day lives. There’s also the way he acts without necessarily understanding; I think that’s part of his appeal.

How did you first encounter the Lupin series yourself as a viewer?

In kindergarten, when I was about six.

What struck you then about the series and the character?

He was different from the heroes I was used to — they were unbeatable, almost cheating in a way. Lupin would get the gang together and go on missions, but the members of his gang weren’t clichés. They seemed like they had real, grown-up relationships.

Your work on the series began as part of the creative team on The Woman Named Fujiko Mine, a radical reinvention of the Lupin formula — taking it darker where Miyazaki, for example, took it lighter. How did your involvement come about, and what lessons did you take from it?

Sayo Yamamoto [chief director of The Woman Named Fujiko Mine] was my junior, and she asked me to get involved. I loved Lupin, and I wanted to work with Monkey Punch’s original manga, so I said yes.

When I did character design for my own work, I only had to consider my own ideas. In this case, Yamamoto was the director, so I also had to take her ideas into account, which was new for me. It was an interesting and valuable experience.

Since that project, you’ve helmed a series of mid-length and now feature-length sequels to Fujiko Mine. The chance to craft a continuous story across multiple anime films is rare. Did that give you creative freedom?

I did have quite a bit of freedom, yes. I asked the producer if we could bring [film director and screenwriter] Katsuhito Ishii on board as a creative advisor, and we had Yuya Takahashi as screenwriter. The three of us shared a fondness for the first Lupin series. We especially liked episodes where there was a strong villain pitted against Lupin. I didn’t really feel restricted in any way.

There have been so many iterations of Lupin — twelve feature films, countless anime serials and specials, and of course Monkey Punch’s original manga. When you’re faced with a new Lupin project, where do you start?

We start by deciding what to keep and what to try anew. We wanted a structure that set Lupin up against a worthy opponent, but we wanted the villain to feel fresh. Ishii-san came up with character ideas — rough sketches, notes about traits, and ideas for key sequences, such as when Lupin goes up against Jigen. Sometimes it’s drawn, sometimes written. That’s how we bring in new ideas.

Your films are known for hyperkinetic action, bold shadows, and rich detail in characters, machines, and motion. How would you define your animation style?

The keyword for me when I’m drawing is dynamism. That’s what I’m trying to express, and I achieve it by emphasizing shadow — it’s all about balance.

You seem drawn to ensemble narratives — not only in your hard-boiled take on Lupin, but also in earlier works you contributed to, like Party, which are ensemble pieces centered on revenge. Did those experiences influence you?

I’m not particularly fixated on revenge stories, but when you set something in the underworld — in the world of the yakuza or the mafia — you have a lot of storytelling freedom. As for ensembles, yes, I suppose you’re right. [laughs] Sometimes it’s easier to understand a character through what others say about them than through what they say about themselves.

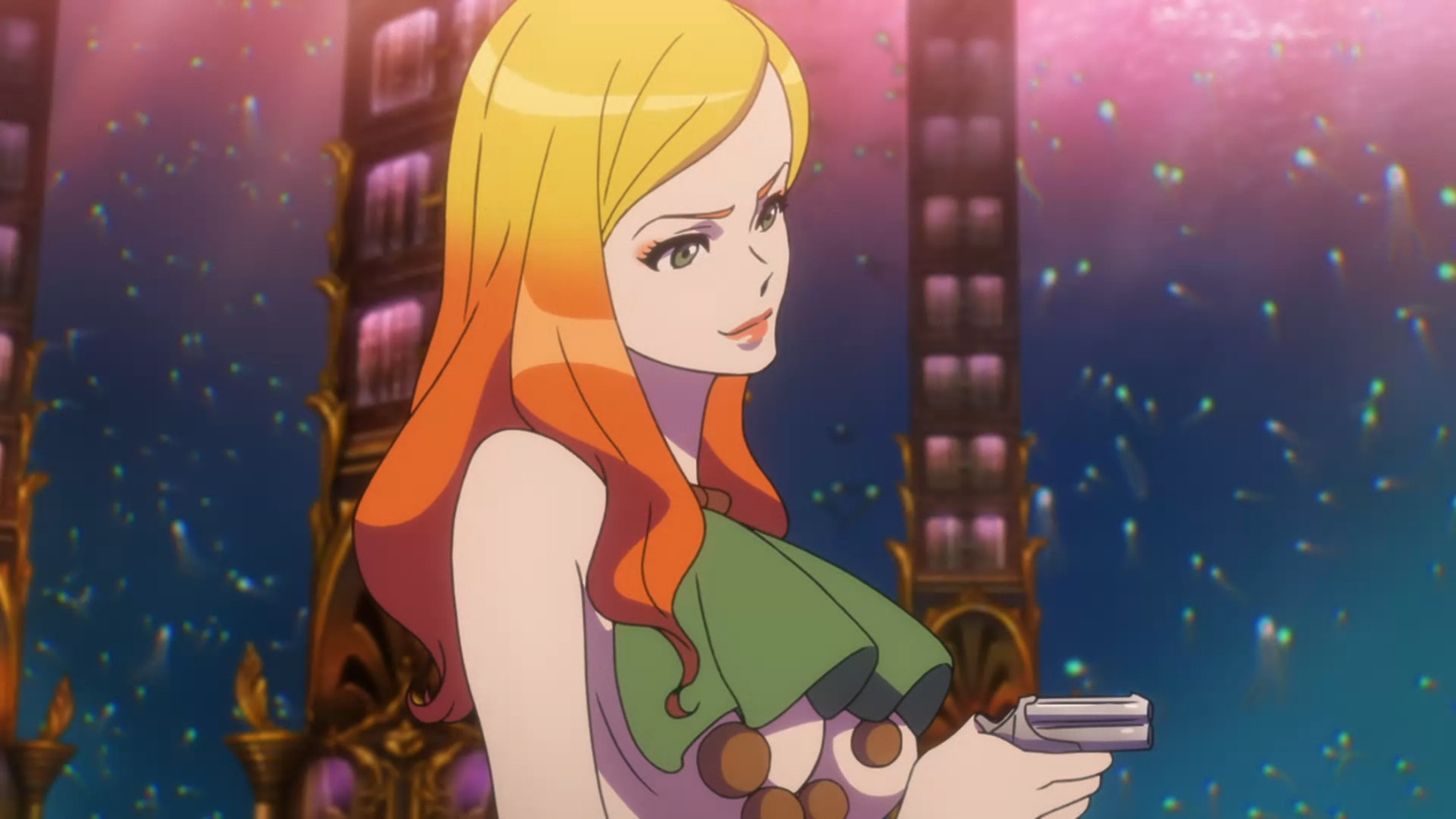

To speak on one specific character, Fujiko Mine is enduring and iconic. While the nature of her hypersexualization has changed over the years, that defining trait has remained constant. How did you approach reinventing her?

I did want to create a woman any man would appreciate — and yes, there are a lot of fan-service shots. But I wanted to focus on the situations I put her in. If I place Fujiko-chan in this situation, how would she react? What would her expression be? How would she cope? I enjoyed thinking through those situations while storyboarding.

Tell me more about your friendship and long collaboration with Katsuhito Ishii. Your career began with the animated opening of Ishii’s Party 7, and the two of you have teamed up many times since.

Ishii-san has made films and commercials. He always has interesting ideas and characters. He originally wanted to be a manga artist, so he’s good at drawing as well.

For example, the character Muom in this movie was inspired by the alien in Ridley Scott’s Prometheus. That was Ishii’s starting point — although the final character is so different you’d never guess. He wrote a detailed profile of Muom, right down to his complexes. It was so convincing it made me want to see the character come to life.

Redline builds expansive world-building in just a few hours, and it remains your most internationally recognized work. What was the starting point for that project, and how do you feel about it?

The starting point for Redline… well, I love cars. I was talking with Ishii-san about what to make next, and that came up. How about a car race? How would we make it special? We talked about a cannonball-style race — and then, what if we made it sci-fi? Set it in space? Then we could have all these fictional planets. That’s how it began.

Film influences on Redline seem clear — Mad Max, Star Wars: Episode I, perhaps even the climactic chase in Adolescence of Utena. Were those conscious?

Mad Max is one of my favorite films, so I was definitely conscious of that “car action.” But I couldn’t make it exactly the same. I liked the desert setting, so I used that in Redline. I also like Star Wars, and I think maybe Ishii-san noticed the Star Wars books on the shelf above my desk — maybe that’s how it ended up becoming sci-fi.

Would you ever return to the Redline universe?

Personally, I’d like to make another animation in that world. But I don’t have as much energy as I did back then, and I don’t have the same team around me — so it would be tricky. But if the chance came, and the timing was right, I’d like to.

Why do you think the Lupin series remains so beloved around the world?

I can’t speak for everyone, but for me, there’s something about his actions — the way he may not help in a clichéd way, but ends up helping nonetheless. He might not say it in words, but he shows it in his actions. That’s attractive.

What excites you about working in animation?

First and foremost, I love it. As a child, I loved drawing, and I was amazed when I saw pictures move. I still feel joy watching that — and the same joy creating it.

It’s been suggested that The Immortal Bloodline is a send-off for your era of Lupin. Are you really passing the baton and hanging up the blue jacket?

It’s the conclusion of this series, which started with Jigen’s Gravestone. I’ve tied up all the loose ends. I’ve also managed to build a bridge back to The Mystery of Mamo (1978), a film I really love. I think I’ve brought it together nicely.

Your films show that the possibilities of animation are limitless. Where do you see your career heading next?

There are some titles I’d like to work on, but I haven’t decided which direction to go yet. I don’t mind whether it’s manga-based or original. Just like when I watched animated movies as a child and was inspired to make them myself, I hope my animation inspires young people to create. For me, that’s the point.

Who is your favorite Lupin character?

That would be Fujiko Mine. She’s cute, she’s attractive, she’s fun to draw — fun to create scenes for. Yeah, I love Fujiko Mine.

Special thanks to Bethan Jones for translation.

.png)