When Classical Music And Cartoons Mingled: How Friz Freleng’s ‘Rhapsody In Rivets’ Became “A Working-Class Fantasia”

Cartoon Brew is pleased to present an exclusive excerpt from the new book Anvils, Mallets & Dynamite: The Unauthorized Biography of Looney Tunes by Jaime Weinman. The book can be purchased from the publisher’s website.

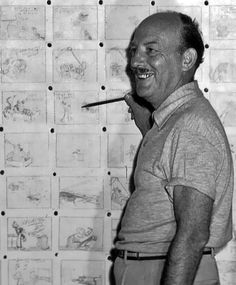

Isadore Freleng – known as “Friz” everywhere except the Warner Bros. cartoon credits, where he was forced to be billed as “I. Freleng” for many years – directed more Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies than anyone else, and directed more Academy Award-winning cartoons than any other Looney Tunes director. He was known for being somewhat risk-averse; he would eventually concentrate most of his energy on only two series, the Tweety and Sylvester cartoons and the saga Yosemite Sam, the character he created as his main antagonist for Bugs Bunny.

But his cartoons were as funny as anyone’s, and he was renowned for his incredible skill at timing, especially in a cartoon subgenre that he made his own: the classical-music cartoon, where the humor comes from seeing cartoon characters move to the rhythms of a familiar piece of instrumental music. In 1941, Freleng used this format for a one-shot cartoon called Rhapsody in Rivets, written by story man Michael Maltese, who would go on to write many cartoons in this format for both Freleng and Chuck Jones.

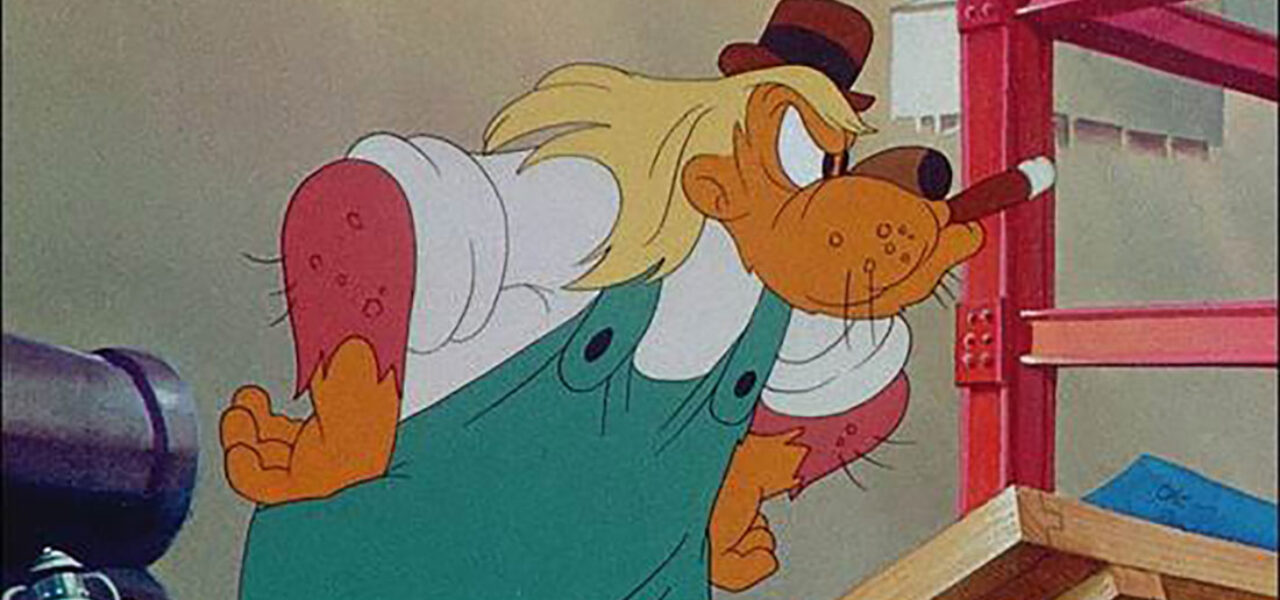

It’s built around an orchestral arrangement of Liszt’s Second Hungarian Rhapsody for piano (which might be the most-used piece of classical music in all animation). The characters are construction workers, acting as if their tools were musical instruments. The short earned Warner Bros. an Academy Award nomination and inspired Freleng to make an immediate follow-up, Pigs in a Polka, where the story is “The Three Little Pigs,” and Liszt is replaced by Brahms.

Classical music was in its last period of prominence in American popular culture, with NBC broadcasting regular concerts by its in-house symphony orchestra under Arturo Toscanini, and movie studios putting out films like The Great Waltz and 100 Men and a Girl (where the girl was Deanna Durbin and the hundred men were a symphony orchestra). In 1940, Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator featured two memorable scenes built around orchestral classics, and that same year, Disney released Fantasia, an ambitious suite of very expensive, mostly serious interpretations of classical pieces.

Freleng’s film has been referred to as “a working-class Fantasia.” While Disney dealt almost exclusively in scenes from the past or fantasy, including prehistoric dinosaurs, mythological gods, and sorcerer’s apprentices, much of the fun of Rhapsody in Rivets comes from seeing Disney’s music-appreciation project applied to a modern city. If Disney was striving to make animation highbrow, Freleng was stripping away some of its pretensions and connecting it to everyday life. He and Maltese approached the classics in the spirit of an American who listens to Toscanini broadcasts and records of Liszt and Rossini and Wagner but refuses to be highbrow about it.

Rhapsody in Rivets, like many such films, puts the emphasis on the music by including no dialogue and no sound effects while the music is playing (except sounds that can be created by musical instruments, such as a triangle imitating a hammer on a nail). It also has a plot that, even for a Warner Bros. cartoon, is simple. With their foreman acting as the “conductor,” a construction crew erects an entire skyscraper in sync with Liszt’s famous piece. After they finish the building, it falls down. The story, as in many cartoons to come, is an excuse for a series of gags.

A few of those gags are about classical music in general. The foreman’s long hair and solemn manner are a reference to the famous conductor Leopold Stokowski, who had just conducted the music for Fantasia, and who Bugs Bunny would famously impersonate in Maltese’s story for Chuck Jones’s 1949 cartoon Long Haired-Hare. But the majority of the gags are synchronization gags, derived from how the action relates to the music, sometimes moving with it, sometimes contradicting it.

Freleng’s film is a showcase for how rhythm and motion alone can create laughter when the timing is perfect. A bricklayer puts down an entire row of bricks in time with the music, and then pants in exhaustion, also in time with the music. A little man tries to climb up a ladder to a few bars of music, only to be forced back by someone else climbing down to the next few bars. The foreman holds up a “STOP” sign to signal that the first section is over; everyone and everything freezes until the recapitulation begins. In a sequence where light chords are answered by heavy chords, the visual equivalent is a tiny worker leaning in to hammer on a big wooden peg, and then leaning back again as his co-worker smacks the peg with his own, gigantic hammer. We all know the little guy is going to get hit with the hammer, but the biggest laugh comes from the matching of movement and character design to music.

Liszt’s piece ends with a trio of notes, right after the loud chords that we think are final. Here, those notes work with a running gag about the foreman hitting a goldbricking worker on the head with a brick: after that same worker is responsible for the building collapse, the foreman is about to throw one more brick when three other bricks fall on his own head to the accompaniment of those three notes.

Such a strongly rhythmic, timing-based approach to storytelling calls for a similar type of animation, more concerned with precision than the fluid, beautiful movement of Fantasia. Freleng’s animators often worked in a style that lacked fluidity, with characters popping from pose to pose; they’ll turn their heads sideways and down and then, on the beat, bounce back to an upright position. It isn’t always beautiful, but it emphasizes the rhythm on Freleng’s bar sheets. Freleng is also perfectly happy to repeat animation when the music repeats: it may save a bit of money, but it’s also funnier to watch the exact same thing happen more than once, and the literal repetition also makes it funnier when something different happens on the third or fourth try.

What we’re seeing in Rhapsody in Rivets, or in other cartoons from the same period with this kind of sharp, split-second timing, is the development of a new comedic language, and every Warner director has his own variant of it. The precision of the movement, the sudden slowing down and speeding up, the surreal warping of time where many things happen in an absurdly short moment. And above all this, the constant promise that the next gag will happen when we don’t expect it, combined with the assurance that whenever it does happen, it will feel as right as the soloist’s entry in a piece of music.

From Anvils, Mallets & Dynamite:The Unauthorized Biography of Looney Tunes. Copyright © 2021 by Jaime Weinman. Reprinted by permission of Sutherland House Books.

.png)