Why Director David Derrick Needed To Follow Up ‘Moana 2’ With An Uncompromising Webcomic

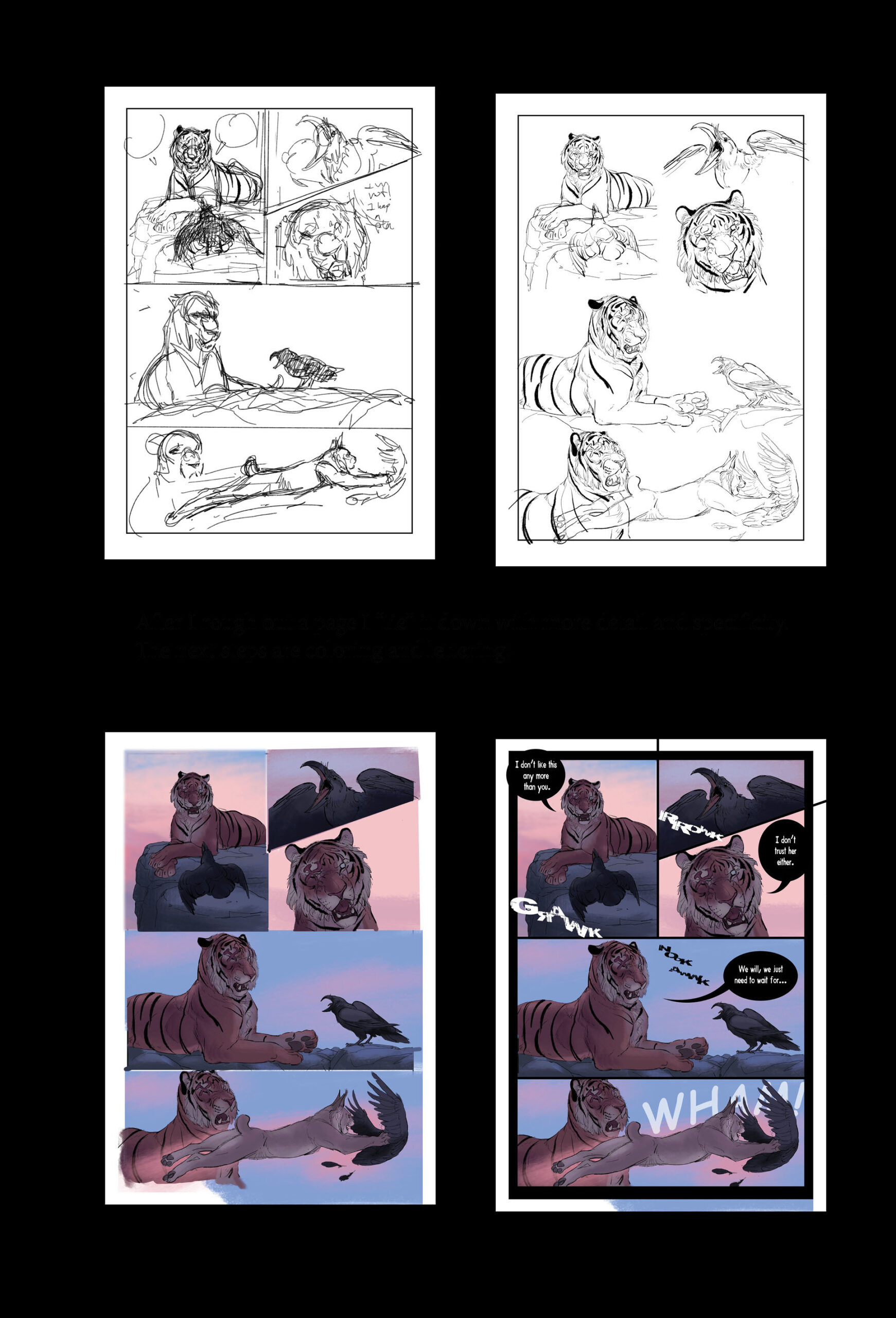

For much of the past decade, David Derrick Jr. has worked at the biggest studios in the world of animation, including DreamWorks, Disney, and now Warner Bros., helping shepherd massive four-quadrant projects across the finish line, most recently the billion-dollar blockbuster Moana 2. Ghost of the Gulag, his stark, hand-drawn webcomic set in the Russian Far East, was born from a desire to step away from that system entirely.

“I want to create things,” Derrick tells Cartoon Brew. “I want to be very selfish. I don’t want to make something that the studio is going to want to buy.”

That impulse, selfish in the purest and most honest sense, led Derrick to a story few major studios would ever greenlight: a brutal, mythic fable about a tortured, blind Amur tiger moving through a landscape shaped by violence, tribal conflict, and the long shadow of Russian history.

“I want to tell a gritty, dark story,” he explains, citing formative influences like Watership Down and Princess Mononoke. “Something that combines dark, messed-up Russian history with these animal clans, the wolves, the boar, and all these allegories that come with it.”

Stepping Outside the Studio System

Derrick’s departure from Disney came shortly after the release of Moana 2, a film whose scale and success only clarified his need for a change.

“Ultimately, I feel like there’s times for every artist when you need to just move on, when you need to find a new mountain to climb,” he says. “Disney was a good experience, but I was more than ready to move on.”

Working inside massive media conglomerates, Derrick notes, requires constant negotiation. “You’re making a lot of concessions creatively to get something that everyone can agree on,” he says. “And sometimes you need a place where there are no negotiations at all.”

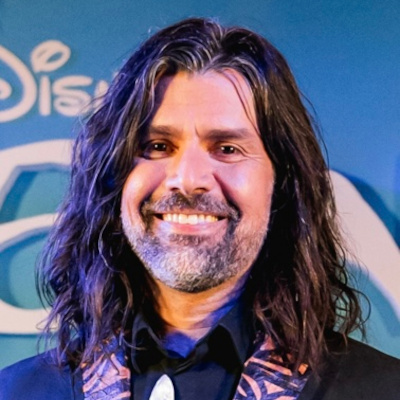

Ghost of the Gulag became that place, a creative refuge during crunch periods on studio films. “Sometimes it became so very stressful,” he admits. “I found working on my comic was like this refuge. There were no concessions. It was literally just me creating in a raw, visceral way.”

A Living Comic

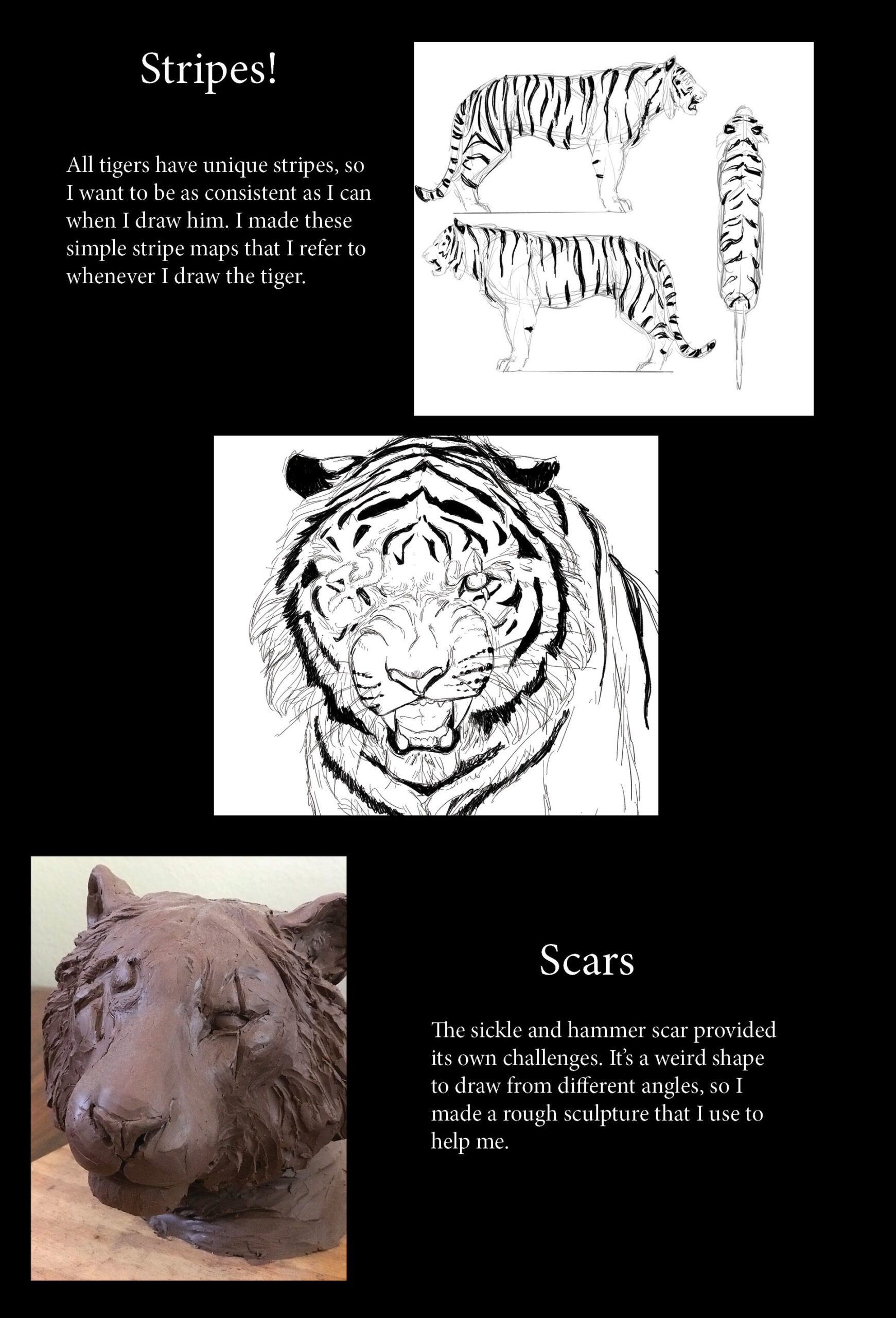

Unlike a locked feature film or more commercial comic book or graphic novel, Ghost of the Gulag evolves in the public sphere with input from its readers. Derrick posts chapters online for free and reads every comment.

“I love the idea that I can put something out and immediately get feedback, what’s working, what’s not,” he says. “I have definitely changed things to make sure the story point I want is landing.”

That feedback loop mirrors animation’s screening process, but without executive filters. The result is a living project, one that grows organically rather than racing toward a fixed delivery date.

“I found a pace,” Derrick explains. “Typically, I publish on Mondays and Thursdays. There are times I can’t meet that, especially when studio work gets crunchy, but I try to keep an honest contract with the readers.”

Drawing as a Native Language

Though known globally for CG features, Derrick insists drawing has always been his primary mode of expression.

“Drawing is the way I communicate,” he says. “It’s the way I express myself ever since I was little.”

Transitioning from disposable story sketches to polished, print-ready panels required developing new muscles. “[Animation] Story artists can crank out hundreds of panels fast,” he notes. “But everything is meant to be thrown away. This was about taking something to final.”

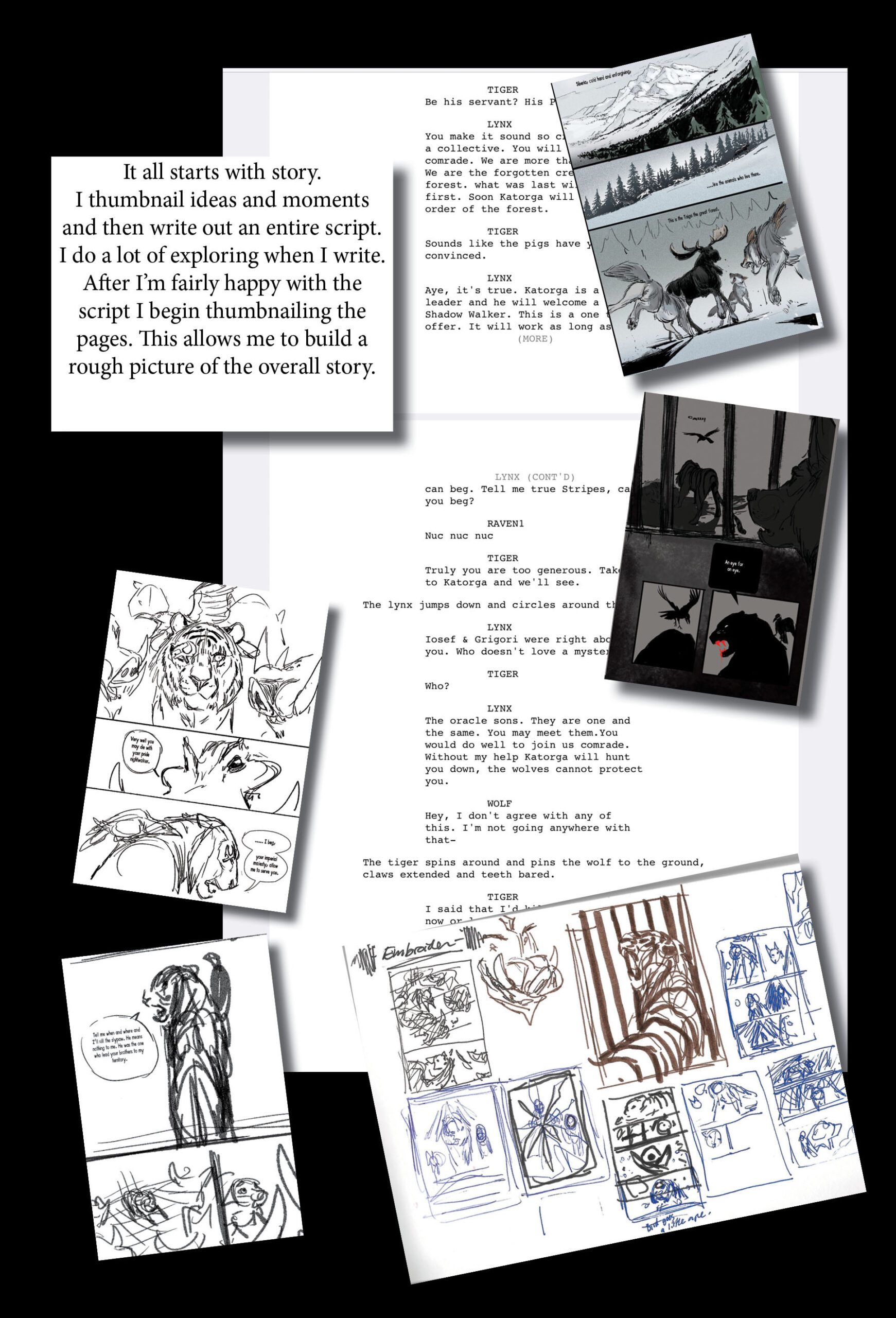

Animals, in particular, have long been Derrick’s obsession. “When I grew up, you’d always hear, ‘Don’t anthropomorphize animals,’” he says. “But anyone who’s lived with a dog or a cat knows they have emotions. It’s about finding what’s already there and pushing it, while staying true to anatomy.”

Why Side Projects Matter

Now at Warner Bros., developing original projects, Derrick still treats Ghost of the Gulag as essential, not optional.

“If you’re not careful, the voice that made you hireable gets swallowed by the giant amoeba of a corporation,” he says. “To make yourself more valuable, you have to define yourself outside that system.”

He encourages younger artists to cultivate their own creative outlets, even when exhausted by production schedules. “Make art for art’s sake,” Derrick says. “You can’t control success, but you can control what you make. Put all your pride into that, and good things will follow.”

The Long View

Derrick is careful not to frame Ghost of the Gulag as a pitch or a product. It may never be adapted, sold, or monetized, and that is precisely the point.

“I don’t think you always have to think, ‘I need to sell this,’” he says. “Sometimes it’s just something you can finish, something you can put a little bit of your soul into. That replenishes you.”

In an era of AI-generated images and risk-averse franchises, Ghost of the Gulag stands as something worth recognition, a handmade work shaped by one artist’s instincts, contradictions, and patience.

Or, as Derrick puts it more simply, “For people who feel like they have to create, creating is like breathing.”

.png)