‘Animation Became The Only Honest Way Forward’: The Ethical Weight Of Animating Real Life In Climate Migration Doc ‘Black Butterflies’

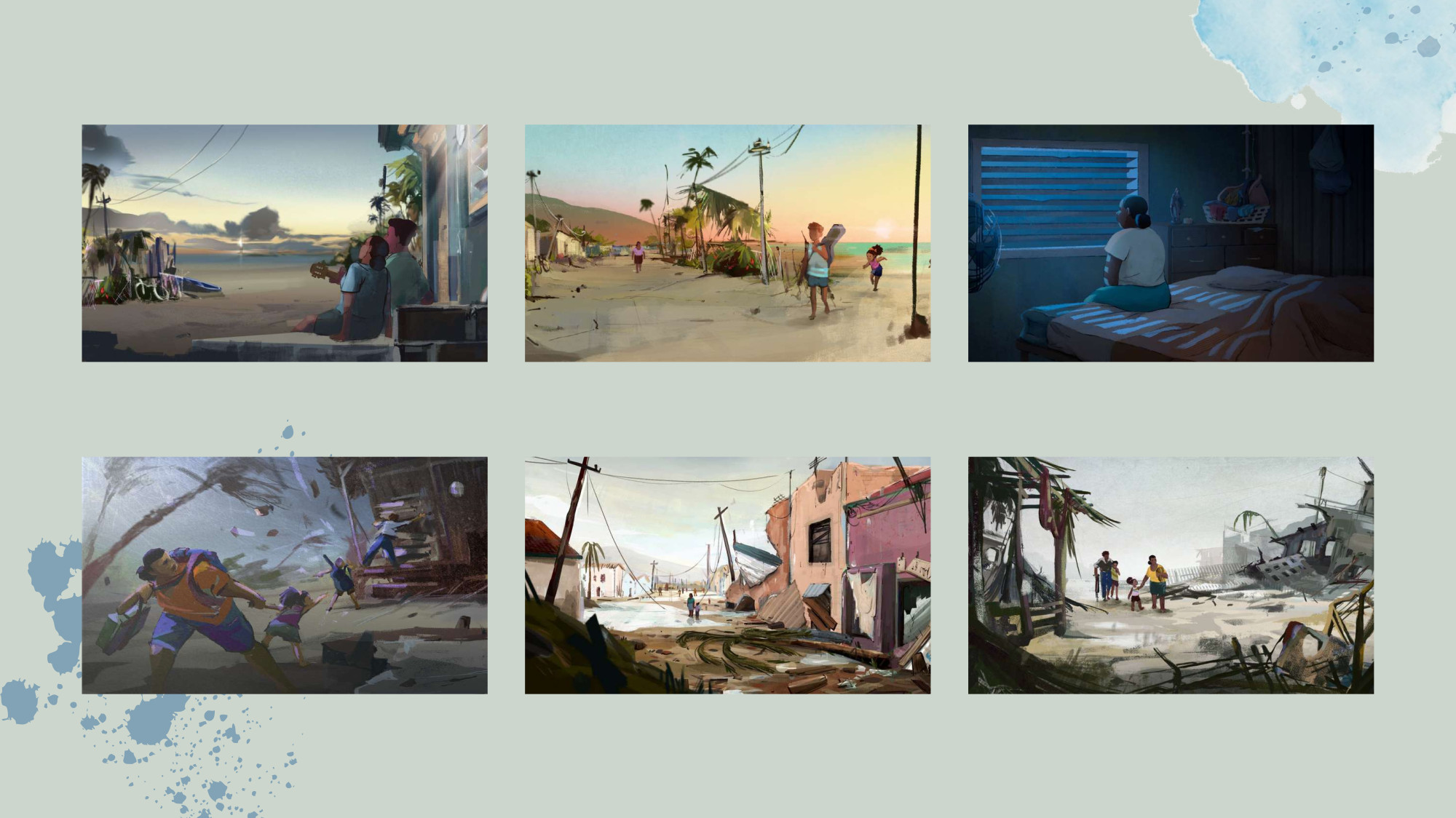

David Baute’s Black Butterflies (Mariposas Negras) is an animated documentary grounded in years of real-world field research and firsthand testimony. Following three women displaced by climate change across the Caribbean, Africa, and South Asia, the film uses animation not as abstraction, but as a way to reach places that a live-action documentary could no longer go.

We spoke with Baute and leading Spanish producer Edmon Roch about why animation became essential to the film, the ethical responsibility of depicting real lives through drawings, and how Black Butterflies fits alongside more commercial projects in Roch’s eclectic filmography.

The director also gave us access to a clip from the film and explained its importance to the vital message delivered in Black Butterflies.

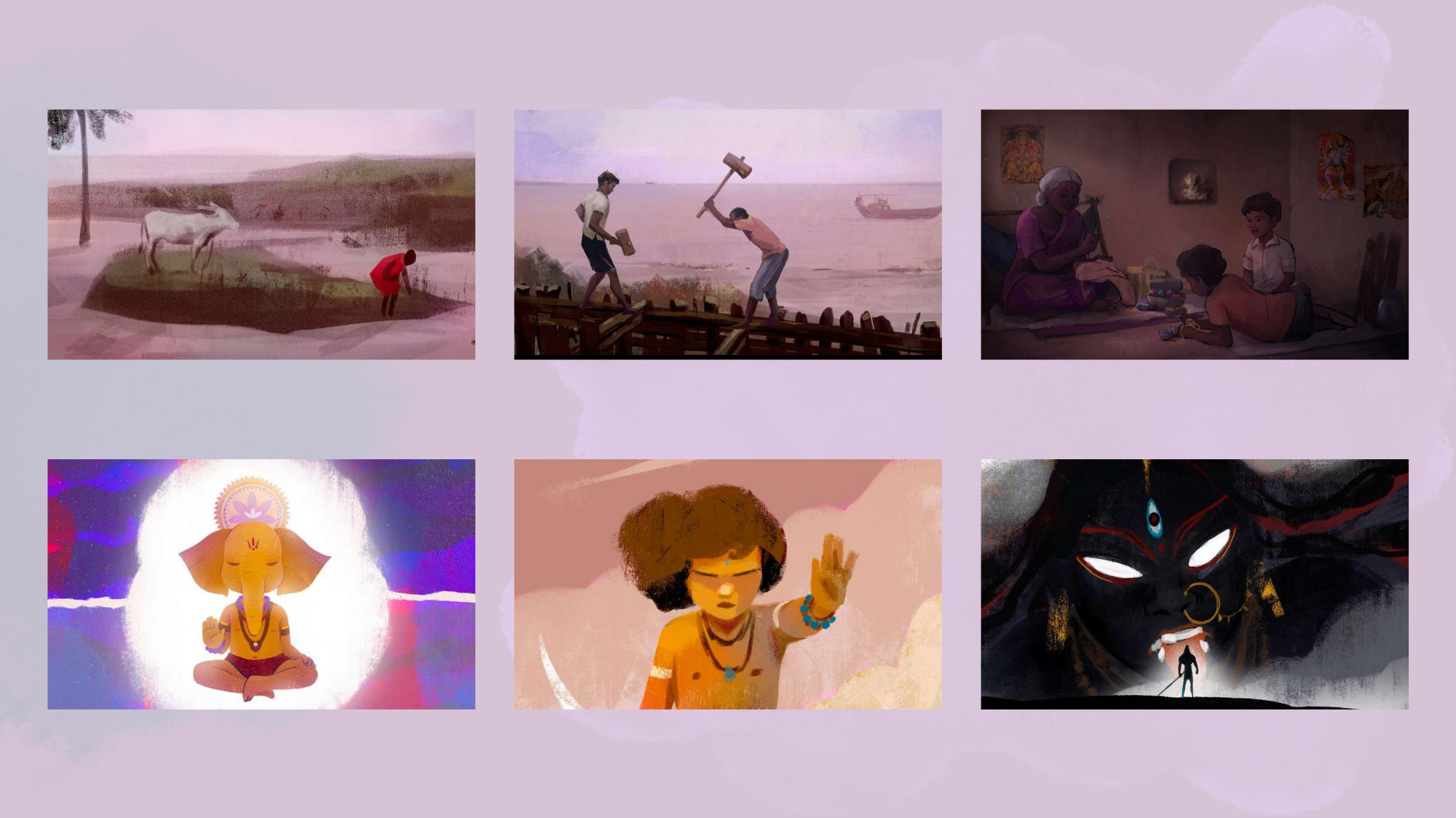

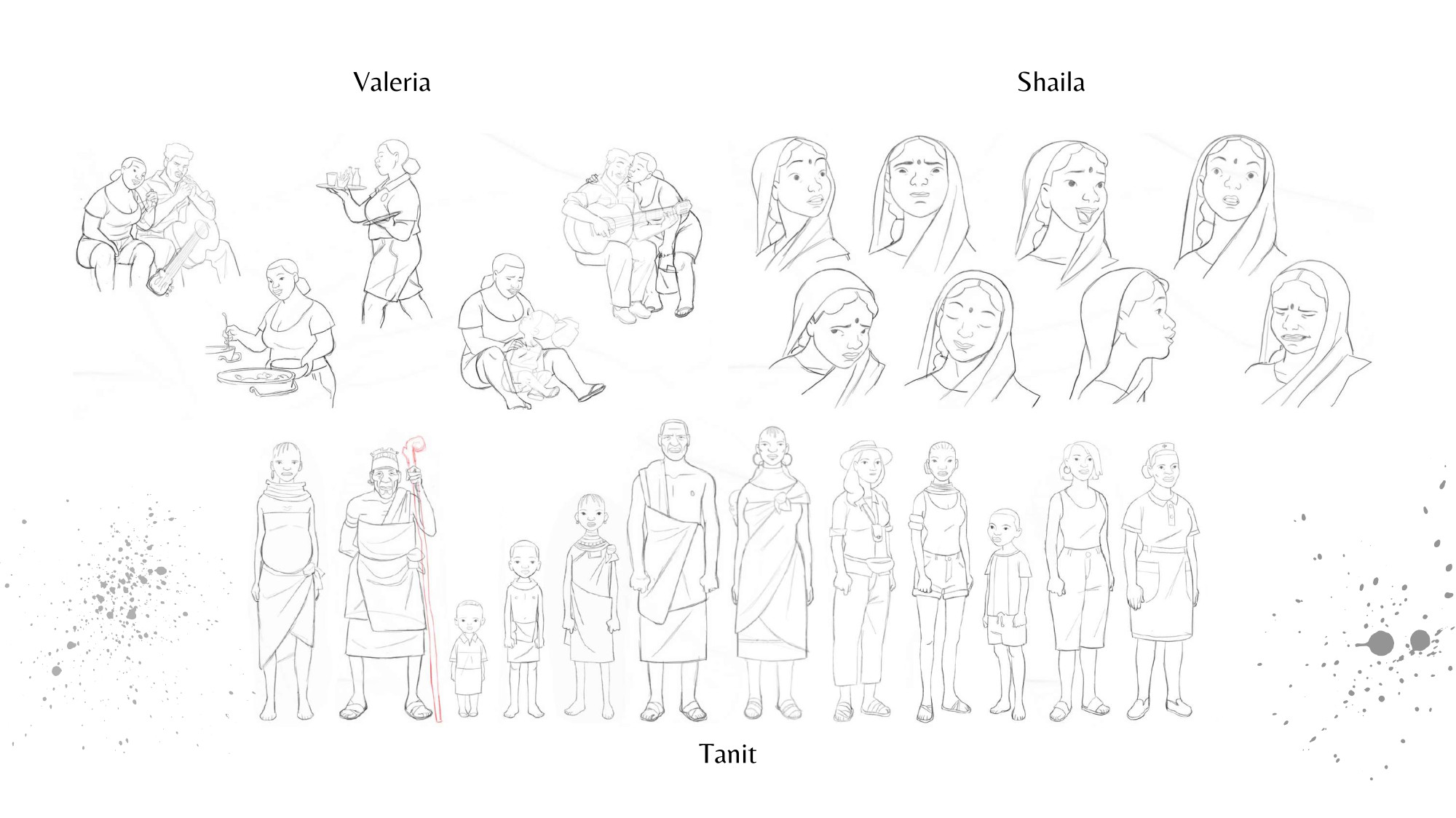

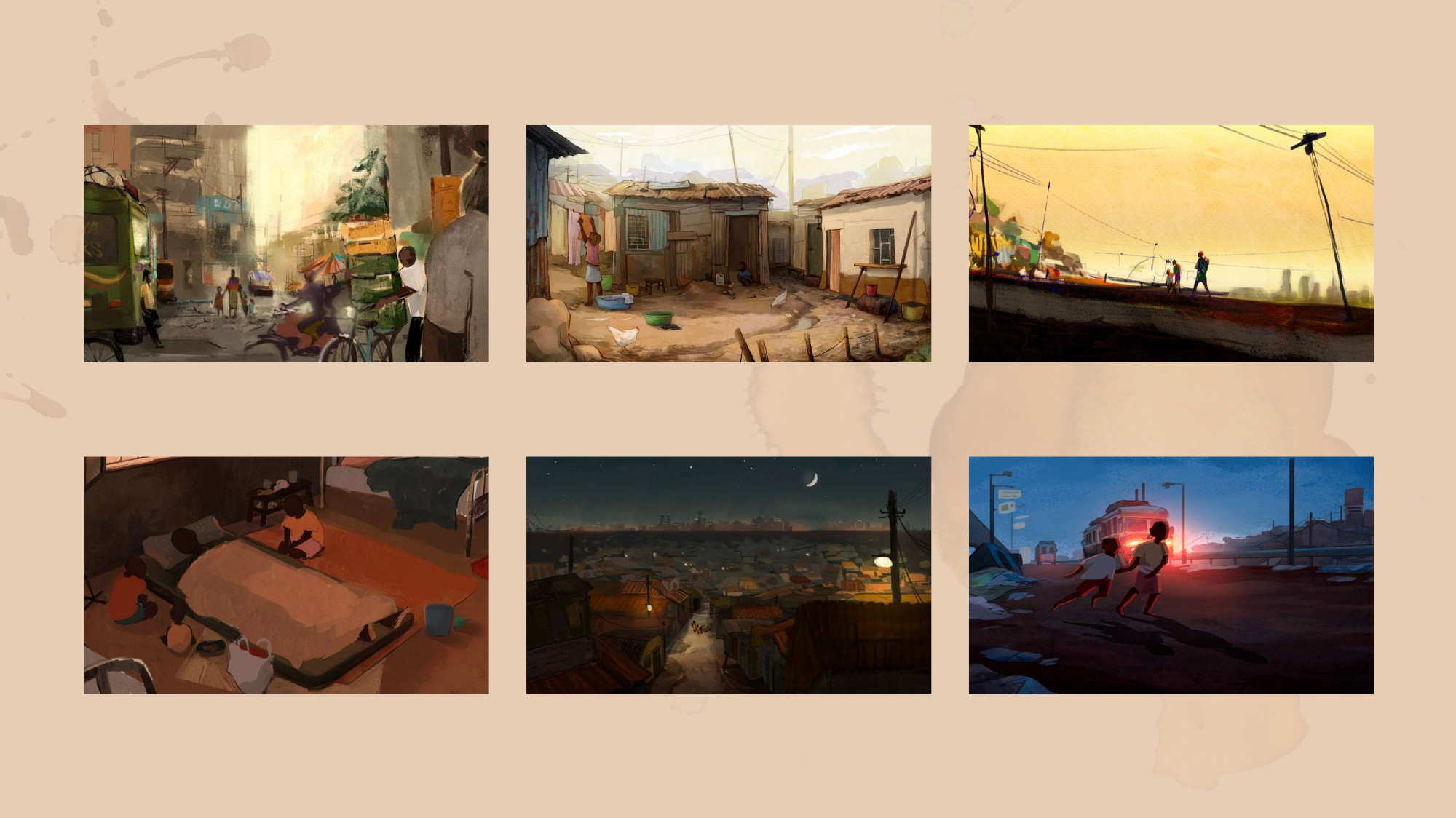

Mariposas Negras is inspired by the lives of three women who lose their homes and culture as a result of climate change. Produced over thirteen years, the film involved a highly sensitive process of development and research in the places where the three stories unfold: Tanit (Turkana / Kenya), Valeria (Island of Saint Martin / Caribbean), and Shaila (Ghoramara / India). This approach imbues the film with authenticity and truth.

It is an independent film whose artistic and animation work in Blender originated in the Canary Islands, with a budget of two million dollars. This has not hindered its journey through international festivals or its receipt of awards such as the Goya for Best Animated Feature in Spain and the Platino Award for Best Animated Ibero-American Film.

We believe the film deeply affects the viewer, stirring awareness through a poetic, auteur-driven perspective on humanity’s greatest current challenge: climate change. Through its dissemination and with your support, we seek recognition of the figure of the “climate migrant.” Global warming is the leading cause of migration worldwide — a humanitarian tragedy for which we are responsible and which is destroying the lives of millions of people. It is an emergency ignored by the international community and by governments in countries where respect for the planet and for human beings has been sidelined.

Cartoon Brew: Black Butterflies began as a live-action documentary. At what point did you realize animation was not just an option, but a necessity?

Baute: We started the project the way I’ve always worked: as a documentary, following real people over many years. We filmed extensively and stayed in close contact with the women whose stories shape the film. But there came a moment when we simply couldn’t keep filming.

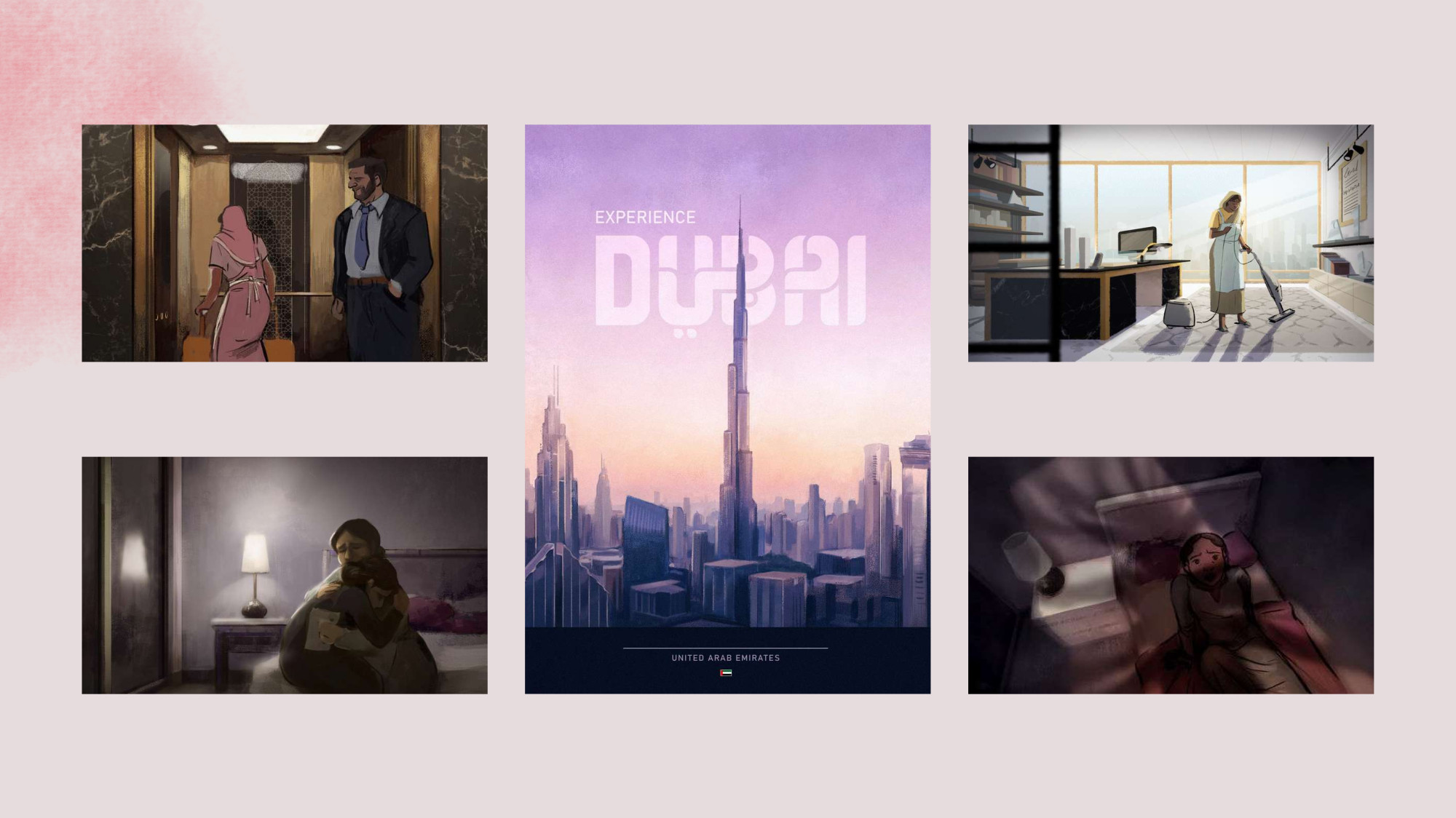

Once climate displacement happens, people scatter. One of the protagonists was taken by an agency to work in Dubai, where filming was impossible. Another had to move to the outskirts of Nairobi and ended up surviving in very dark conditions — prostitution, extreme precarity — places we could not ethically or practically enter with a camera.

And yet, that final part of their journey was essential. In fact, the film begins there, with them already displaced, dislocated, doing things they never imagined they would do. We wanted the audience to understand how they arrived at that point, and that’s where animation became the only honest way forward.

We could either fictionalize the story and shoot it in live-action with actors, or translate everything we already knew — the years of documentation, conversations, messages, lived experience — into animation. Animation allowed us to complete the story without betraying it.

You’ve got a decades-long career working in documentary. How did animation change the audience you were able to reach with this story?

Baute: In many ways, it didn’t change how I approached the film at all. For us, it remained a documentary, an unreal form built from very real stories and real facts.

But audiences respond differently to the word “documentary.” Many people avoid it because they don’t want to confront reality; they want entertainment or escape. The documentary audience is often already aware of issues like climate change and migration, and already understands their importance.

Animation opened another door. It allowed us to reach people who might never choose to watch a documentary about climate migration. People who aren’t already engaged with these issues. That was crucial because the reality is that climate migration is still largely invisible, despite being an urgent and growing crisis.

Animation helped the film travel further, into schools, universities, cultural centers, museums, and community screenings. Almost every day, we’re invited somewhere to show the film and talk about it. That gives the film a real function. I like to feel that cinema, and in this case, animation, can be useful, that it can contribute something meaningful to society.

Edmon, from a producer’s perspective, Black Butterflies sits alongside very commercial titles you’ve worked on, like Tad the Lost Explorer or Spain’s 2025 Oscar submission, Saturn Return. How do you balance projects with such different goals?

Edmon Roch: For me, everything starts with the same question: Is this a story I would want to see as a spectator? On a Friday night, at a festival, anywhere in the world, would I choose this film? The answer can be yes for very different kinds of projects. It’s yes for Tad, and it’s yes for Black Butterflies, even though they are completely different. What they share is that they feel necessary to exist.

Of course, as a production company, you need balance. Not every film can be commercially risky, and not every film can be purely commercial. Some projects have strong financial structures and very limited risk; others, like Black Butterflies, are made because they need to be made, even if you don’t know how you’re going to finance them at first.

But I don’t see these films as contradictory. The commercial films allow you to survive. The more difficult films remind you why you wanted to make cinema in the first place.

David, working in animation meant designing characters and environments based on real people and real places. How did you approach that ethically and responsibly?

Baute: That responsibility already exists in documentary filmmaking. People are trusting you with their lives, their stories, and their dignity. You can easily harm them if you’re careless.

From the very beginning, we worked with respect and closeness. We didn’t just arrive, film, and leave. We spent time with people. Sometimes I even ask them to film me first, so there’s a sense that we’re building something together.

When we moved into animation, that responsibility didn’t disappear; it intensified. We were no longer just recording reality; we were reconstructing it. Every house, every landscape, every gesture had to feel truthful, not caricatured or sensationalized.

What I think helped is that the animation team adapted to a documentary language. The framing, pacing, and rhythm are closer to observational cinema than to traditional animation. Even the art direction grew out of the earliest sketches, which felt raw and emotionally honest. Sometimes I think the film could have existed just with those first concepts.

There was also a personal discomfort that never went away. When the film wins awards, you sometimes ask yourself: Do we deserve this? These recognitions are built on the suffering of other people. I understand that visibility can help those stories reach more people, but the question never fully disappears.

Edmon, the animation production itself was unusually structured, without outsourcing to large external studios. Why was that important?

Roch: This film required proximity and constant dialogue with David, as well as among all departments. We built the animation teams person by person, not by subcontracting work abroad. We worked mainly from Tenerife and Barcelona, with a third team in Panama. Everyone was in direct contact, meeting regularly, sharing the same creative space. That closeness was essential because the film’s tone is so delicate. You can’t treat it like a standard pipeline project.

Interestingly, the process also created movement in the opposite direction. Artists who worked on Black Butterflies later moved on to large commercial productions. María Pulido, our art director, later became art director on Tad 4. That exchange goes both ways.

Looking back, what do you feel animation made possible that live action never could have?

Baute: Animation allowed us to tell the whole truth.

Not just the visible truth, but the emotional truth, the internal landscapes, the sense of dislocation, the memory of places that no longer exist. These women didn’t just lose their homes; they lost their relationship to the land, to identity, to continuity.

Animation gave us the freedom to show that without exploiting it. To step back, reflect, and ask the audience not just to watch, but to recognize their own responsibility.

This film doesn’t say, “We’re going to take something from you.” It says, “Can we make a world where others don’t lose everything?” That’s the question we wanted to leave people with.

This interview was translated from Spanish and edited for length and clarity.

.png)