Donald McWilliams — Canadian Animation’s Custodian Of Memory

On a Sunday night in 1959, a young market-research worker in Toronto sent his roommate off to see a re-release of Gaslight. When the roommate came home, Don McWilliams asked the most basic question: Is it worth seeing?

“Yes,” the friend replied. “But what you really have to go for is the short.”

The next day, McWilliams went back to the cinema and found himself staring at Norman McLaren’s Serenal (1959), a scratched-on-film experiment the director himself would later dismiss as his worst work. For McWilliams, it was the opposite. The film, etched directly onto 16mm with a dentist’s vibrating drill, blew apart everything he thought cinema was supposed to be.

“I’d seen Fantasia as a boy,” he recalls, “but Serenal was totally abstract. It completely upended all my notions of what cinema was.”

That one short set the course for everything that followed: decades of work at and around the National Film Board of Canada, a life spent oscillating between documentary and animation, and a role, as much accidental as deliberate, as one of the NFB’s most stubborn guardians of memory.

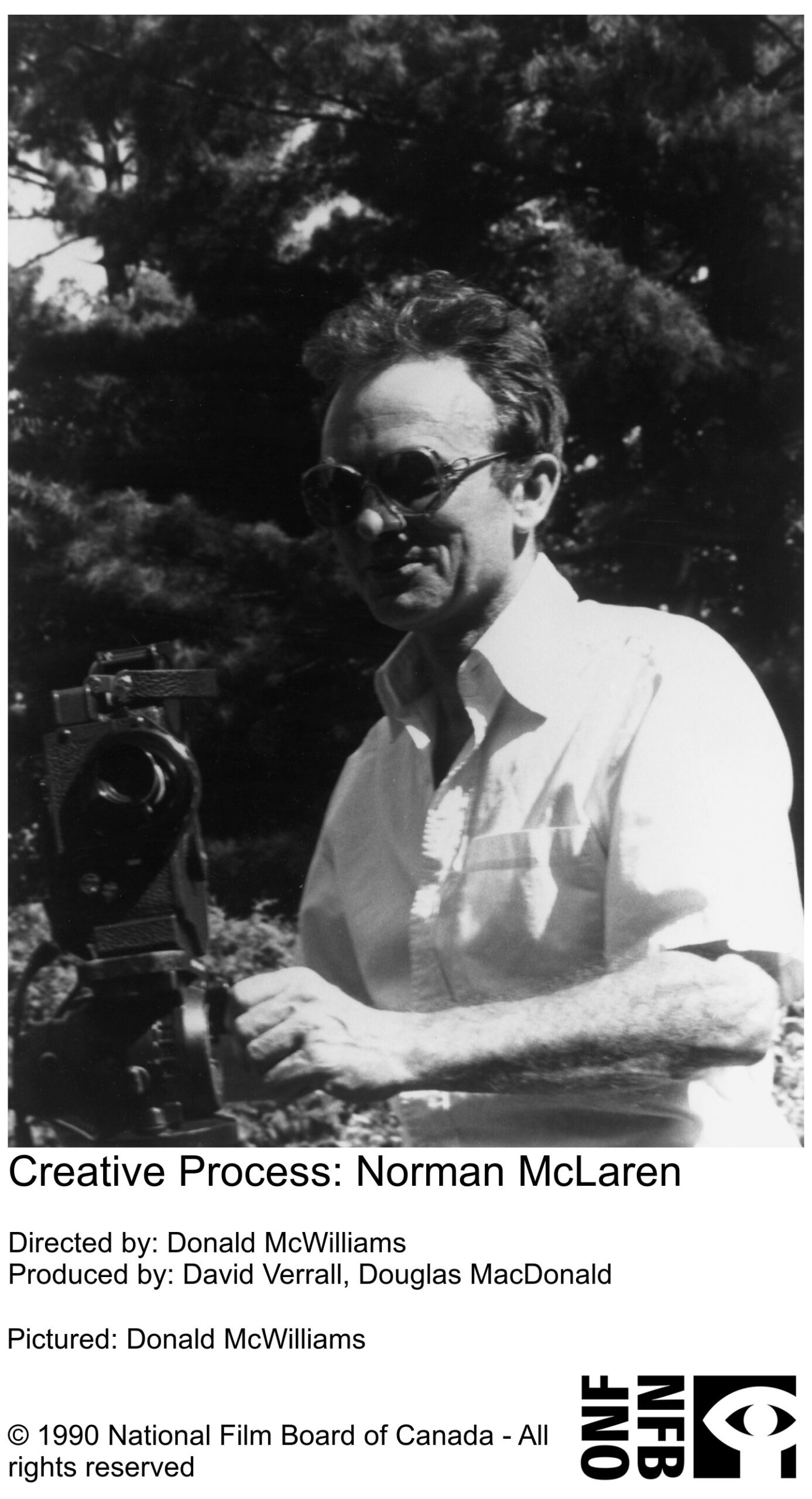

Over the decades, McWilliams has moved freely between documentary and experimental work, often blending live action, archives, and animation in films like Creative Process: Norman McLaren (1990), Norman McLaren: Animated Musician (2014), and Eleven Moving Moments with Evelyn Lambart (2017), which lifts McLaren’s long-time collaborator out of his shadow.

His historical essay films — The Passerby (1995), The Fifth Province (2003), and A Time There Was: Stories from the Last Days of Kenya Colony (2009) — sit alongside his work as producer and editor on the Oscar-nominated Sunrise Over Tiananmen Square. Add in years of teaching experimental animation and documentary in Norway, multiple Writers Guild of Canada nominations, two Focal Archival nominations, and a long residency inside the NFB’s animation studio, and you get the paradox of Donald McWilliams: a non-animator who has become one of animation’s most trusted custodians.

“Donald McWilliams personifies the NFB spirit of risk-taking and creative collaboration,” notes Suzanne Guèvremont, Government Film Commissioner and Chairperson of the NFB. “Over the decades, he has helped shape NFB storytelling through his own poetic, groundbreaking films as well as by mentoring generations of NFB animators and filmmakers.”

Early Encounters With History and Film

The seeds were planted long before Serenal. As a child in wartime England, McWilliams spent endless hours poring over a family book called These Tremendous Years, a compendium of photographs from 1919 to 1938. The pages were crowded with “Hitler, murderers, Lindbergh, all this kind of thing,” and the boy became fascinated with photographs as historical artifacts, images that carried time inside them.

His father added another layer. During the war, he told his son that if he ever had the chance, he should see All Quiet on the Western Front because it showed World War I from the German side. When McWilliams was eleven, he spotted the film on the marquee of a local “flea pit” cinema and went alone on a Saturday. Watching the young German protagonist felled by a French sniper, he realized that cinema was not just entertainment; something deeper was at stake, even if he couldn’t yet name it.

Photography, War, and Leaving England

Later, military service in Africa brought him into a camp darkroom in Nairobi. He bought a Kodak Retina 35mm camera, taught himself to develop and print, and began accumulating images. Still, it never occurred to him that this might be a career.

Back in England in the mid-1950s, unsettled by his time in the army and British racism, he decided almost on impulse to leave. New Zealand House had a queue; the Canadian immigration office did not. “I walked in and asked for pamphlets,” he remembers. “The woman shoved them under the grill, looked at me, and said, ‘Upstairs for a medical.’”

A day later, after a perfunctory exam, the doctor/immigration officer asked where he wanted to go. McWilliams, working for a shipping line, suggested Vancouver. “No, there’s a lot of unemployment in Vancouver,” came the reply. “You should go to Toronto.” McWilliams shrugged and said okay.

Four months later, he was on a converted troop ship bound for Canada, arriving on October 23, 1956, the day the Hungarian Revolution broke out. A week after he landed, Britain, France, and Israel invaded Suez.

In Toronto, he drifted through jobs: The Toronto Daily Star, then market research. None of it quite fit. What stuck was his growing cinephilia, the pull of still and moving images, and that nagging, abstract little film called Serenal.

Teaching, Handmade Film, and the NFB

The transition came through teaching. A friend in Burlington offered him a room if he enrolled at Hamilton Teachers’ College. McWilliams took the deal and ended up at Holy Rosary, a Catholic elementary school run by nuns.

The NFB’s Ontario distribution in those days was a tad informal. Staff would turn up with car trunks packed with 16mm prints, some NFB, some not, and offer screenings to any teacher bold enough to thread a projector. McWilliams was happy to oblige.

He started with McLaren films. “Every Friday morning was ‘McLaren Day,’” he says. The students became fascinated not just by the films but by the how of them. The Board, sensing an ally, began supplying raw stock. McWilliams and his students built glass animation tables. “Every Wednesday afternoon became ‘handmade film day.’”

In 1968, he was invited to the NFB headquarters in Montreal for a six-week Summer Institute of Film Study with about two dozen teachers. From nine in the morning to midnight, seven days a week, they were bombarded with cinema: Brakhage on four screens, Warhol, classes in mime, editing, everything (including NFB docs and animation).

By then, McWilliams was entering his pupils’ handmade films in amateur festivals. One of them took the top school prize at the Scottish Amateur Film Festival, the same festival where McLaren had shown his earliest work. McWilliams used that tenuous thread as an excuse to knock on McLaren’s office door.

McLaren, weary of always being pestered, tried to brush him off until McWilliams mentioned the handmade student films. He reluctantly took one, ran it through the rewinds, and then booked the screening theatre to view all the films. Afterward, he turned to the young teacher and delivered the sentence that quietly changed McWilliams’ life: the films, he said, weren’t copies of his own.

From McLaren, who complained that most handmade films simply imitated him, that was high praise. For McWilliams, it was the beginning of a mentorship.

Learning From McLaren, Editing Like an Animator

By the early 1970s, McWilliams had left teaching, gone back to university for a master’s degree, and begun making industrial films, starting with a film on the newly invented soft contact lens, which he sold to the manufacturer after shooting it at the University of Waterloo. At the same time, he kept returning to the Film Board, where McLaren was schooling him in the mysteries of the optical printer and animation stand.

McWilliams has always described himself as torn between realism and abstraction. His films are mostly documentaries, often built around archival images and historical traces, yet his deepest lessons came from animation. “The animator is focused on the frame and what’s happening in that frame,” he says. Documentary shots, in his view, often simply “come to an end”; the animator obsesses over the last frame at the cut, the perfect gesture to exit on.

He began editing documentaries like an animator. That sensibility runs through major works like Creative Process: Norman McLaren (1990) and The Passerby, which became something of a secret handshake among filmmakers. One colleague told him that The Passerby “completely upended all our notions of what a documentary film is.”

Part of that effect came from technique. McWilliams borrowed the animation mix-chain technique, taught to him by McLaren, a method of dissolving each frame into the next, to give live-action footage a ghostly, flickering quality. It became a visual signature, a way of making the past literally shimmer into the present.

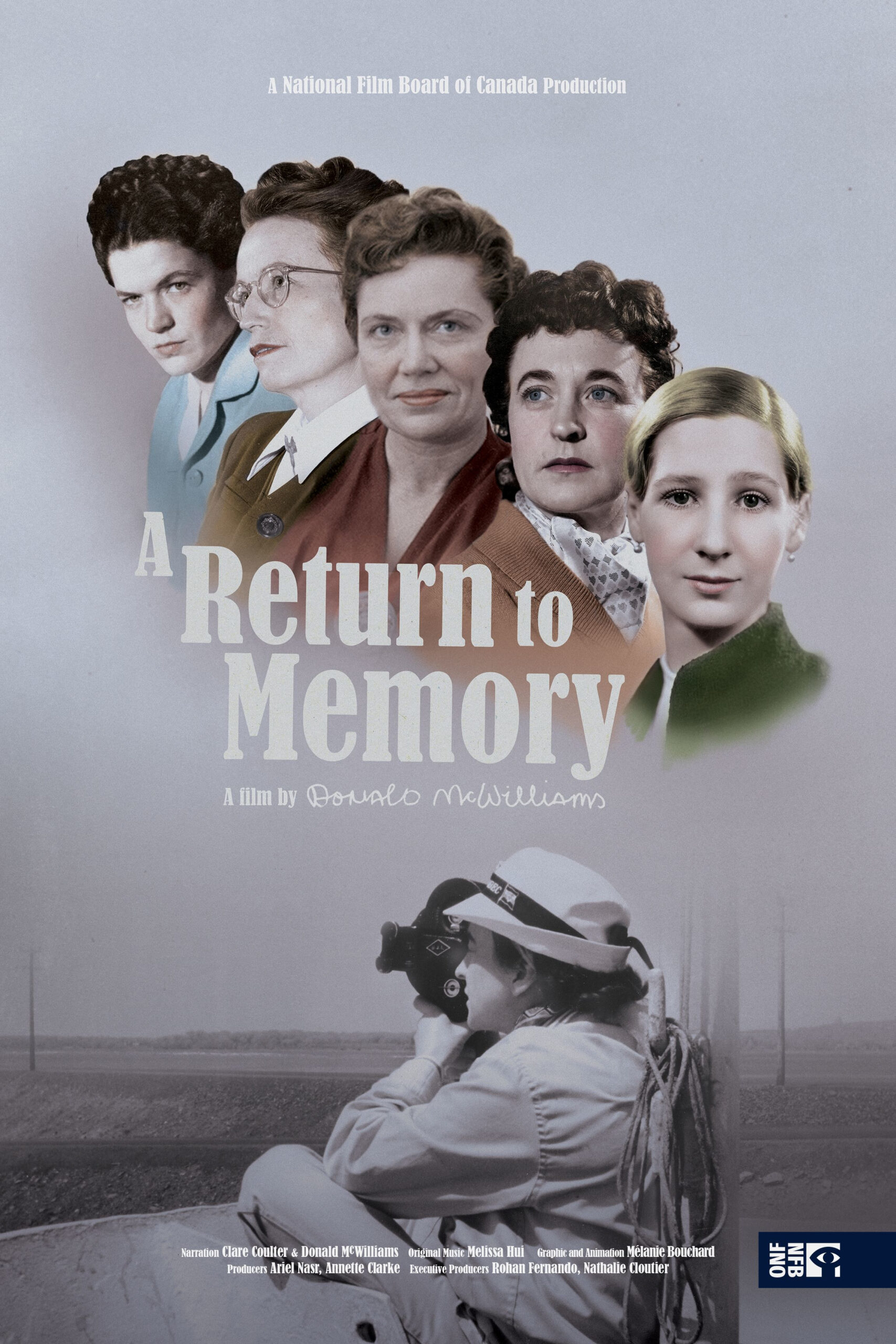

That same mix of archival excavation and animated thinking runs through later works like Eleven Moving Moments with Evelyn Lambart, a film built from Lambart’s films, fragments, and memories, refusing to treat her as McLaren’s footnote, and A Return to Memory, his epic, two-hour tapestry of NFB women and their often-erased histories. Both works underline his instinct to pull overlooked figures out of the margins and into the centre of the frame.

Mélanie Bouchard, who provided animation and graphic design for both films, says: “Don often told me that I can read his mind. In fact, he knows how to explain clearly what he wants and give you the liberty to work it out the way you like. It’s the best collaboration you could wish for.”

“He is a master documentarian, a mentor to countless young filmmakers, and an ardent supporter of experimental animation,” says frequent NFB composer Luigi Allemano, who scored McWilliams’ 2014 documentary, Norman McLaren: Animated Musician. “When Don claims not to be a scholar, he’s being modest—he’s actually a one-man university.”

Working With McLaren Inside the Film Board

In 1980, while helping shoot a complex front-projection film for Patricia Gruben on the NFB’s shooting stage, he would wander upstairs to visit McLaren. He found his mentor despondent, convinced he’d never finish Narcissus now that key collaborators like Grant Munro wanted to pursue their own films. McWilliams, half-joking, half-serious, said, “Why don’t I come and work with you?”

The idea stuck. After a formal process in which McLaren had to officially reject other applicants, McWilliams was given a three-month contract as McLaren’s assistant. It stretched into three years, then into an open-ended relationship with the Board that continues, in one form or another, into his nineties.

Oddly, McWilliams never joined the NFB staff. He has always been a freelancer with a permanent desk. “It gave me freedom,” he says. As a freelancer, he could disappear to Norway to teach for a few years and return to find his office still there.

That semi-outsider status may be part of why so many colleagues see him as the NFB’s conscience. He fought hard against the casual destruction of film elements and played a quiet but significant role in forcing the institution to take its archives seriously. “He is a pillar,” says line producer Mélanie Boudreau Blanchard, praising not just his expertise but his “commitment to safeguarding the essence of the NFB” and his “genuine love for the institution.”

Credit, Conscience, and Institutional Memory

If there is a single story that encapsulates McWilliams’ understanding of the NFB, it starts with a knock on Norman McLaren’s door. A notoriously demanding camera technician, Eric Miller, came in to thank McLaren for something no one at the Board had ever given him in 30 years: a screen credit. After Miller left, McLaren turned to McWilliams. “This is the most important thing I will ever say to you at the Film Board,” he told him. “The man down in the basement mixing the chemicals to develop the film is working to make your film better. You thank everybody.”

McWilliams took that to heart. He links much of his influence within the Board — the mentoring, the trust, the carte blanche for odd projects — to that simple ethic: treat technicians as creative partners, acknowledge the unseen work.

It’s a lesson that echoes through the way others talk about him.

Torill Kove, Oscar-winning animator: “This may be going out on a limb a little bit, but it’s almost like Don’s presence at the NFB helps us feel good about ourselves and our continued pursuits there. It’s like he validates our place in the NFB’s history. Sometimes I think the NFB is Don’s country, and Don is an ideal citizen in that he cares about the past, present, and future of the NFB, and he also cares about the people in it.”

Producer Marcy Page frames his career in moral as well as aesthetic terms. For her, McWilliams’ true medium is memory: from “baring the moral dilemma of a young conscript in Africa” to documenting wartime massacres and resurrecting eclipsed NFB filmmakers, all the way to his meticulous restoration and contextualization of McLaren’s experiments. “I recently told him that he is a welcome voice in my head,” she says. “We can all use a touchstone, a better angel.”

“Don has a gift for recognizing patterns,” adds Maral Mohammadian, NFB producer. “He makes connections between disparate ideas. He also has a rambunctious spirit. On a personal level, I just love talking with him. He helps me recalibrate. He cuts through the noise and reminds you what’s important.”

McWilliams sees the NFB’s survival as a matter of continuity. He remembers a colleague once putting an arm on his shoulder and telling him, simply, “You are a heritage.” For those who’ve been around, he says, “the whole question of continuity is very important.” Norman McLaren introduced him to people who became his mentors — Maurice Blackburn, Tom Daly — and because he was with McLaren, “they tended to take me more seriously… so I became part of the fabric of the place.” The years have made him, almost by default, a living repository. “The business of tradition and continuity is so important,” he says. “Without that timeline, without that continuity, the Film Board would not be the place it is.”

Asked why he kept returning, coming and going, McWilliams traces it back to the first McLaren film that “caught my imagination,” and then to being “caught up in the whole environment.” As an independent filmmaker, he says, the work could be a grind, but “the Film Board was something much more exciting.” It was also, at the time, “essentially the only game in town”—a hive of staff filmmakers, sound people, recordists, and the energy of Cinema Direct. The NFB gave him an opportunity, and with it loyalty: “People trusted me, and they taught me. I felt I owed the Film Board something, and also Canada.” At its best, he believes, the institution carries a rare dual mandate: “At the National Film Board of Canada, you can be both an artist and a public servant,” and that, he says, is where the conscience comes in.

What the younger generation gives him back is fuel: “I’m still very curious,” he says, and people respond to that curiosity by showing him what they’re making and how things work now. He tries to stay “hands-on,” and to translate “analog thinking” into digital practice, building the kind of relationship where “they don’t try to pull the wool over your eyes.” If anything still surprises him, it’s the small, human continuities: people greeting each other with a smile; technicians who appreciate that, when he’s finished editing, he doesn’t just shut the door and disappear, he makes a point of walking into the room and saying good night to everyone before he leaves. The animation studio remains, for him, “my spiritual home,” and he still looks for that spark in the building, the people who have it, and the way it passes on. After all these years, he says, it comes back to “that central thing of the Film Board being a kind of a family.”

Continuity, Curiosity, and What Endures

In his tenth decade, McWilliams is still at it. His next film, And Yet Oranges, blends documentary and animation, with sequences by Eva Cvijanović and others, circling back through Sarajevo, archives, and the odd, stubborn persistence of images.

For now, McWilliams just keeps editing like an animator, arguing with institutions, making the past move frame by frame, and, as McLaren ordered him to, thanking everybody.

.png)