Secrets Of A Creative Marriage: 10 Animation And Filmmaking Tips From Disney Directors Ron Clements And John Musker

Ron Clements and John Musker call their creative partnership a “self-inflicted marriage.” The history books will be more flattering: Clements and Musker make up the most successful directing duo ever to work at The Walt Disney Company, period.

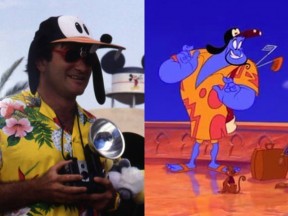

Both coming from backgrounds in story and animation, Clements and Musker flourished in the Disney Renaissance, convincing a skeptical Jeffrey Katzenberg — their boss — that directing in a pair made sense. They helmed (and often wrote) some of the studio’s best-known features, including The Little Mermaid, Aladdin, Hercules, The Princess and the Frog, and Moana. What’s their secret?

The pair reflected on their careers in a good-humored masterclass on Annecy Online, peppering their dialogue with gentle swipes at one another. Their discussion was bursting with advice about animation, storytelling, directing, and the creative life in general. We’ve collected the ten best tips below:

1. Tell stories that exploit the medium of animation. The pair try to avoid stories that could be told as a novel or a play. “That rule has become a little blurrier,” admitted Musker, “as live action … moves so much closer to animation, with the introduction of digital technologies.” He’s skeptical about Disney’s forthcoming live-action remake of The Little Mermaid: “I wish them well with that, but [people speaking and singing underwater] is a convention, a stylization, that I think is easy to accept in a hand-drawn film.”

2. You can find characters anywhere you look. Clements gave the example of Glen Keane, who animated Ariel in The Little Mermaid, and whose personality shaped hers: “We thought of Glen [when developing Ariel]. He jumps into things, he’s bold.” He added, tantalizingly, “There’s a few villains that we based on some of our bosses.”

3. Use songs that advance the narrative. The pair discussed their collaboration with songwriter Howard Ashman, who was courted by Disney in the late 1980s, and chose The Little Mermaid from among the various projects on the table. Ashman and the directors agreed that “any song that was in the movie had to advance either plot, or character, or both. [Otherwise] the story was stopping during the song, and we didn’t want that to happen.”

4. Create each scene five times. Clements learnt this lesson from his mentor Frank Thomas, one of Disney’s Nine Old Men: “You get a scene of animation and you think, ‘I know how I want to do that.’ Don’t just go with your first impulse. Force yourself to come up with five different ideas of how to animate the scene, and then pick the best one.”

5. Let the audience see the funny picture. This specific tip was passed down to Musker by Ward Kimball, another of the Nine Old Men, via animator Cliff Nordberg. It’s essentially about timing in comedy — about pausing when necessary. “Sometimes I have a tendency to go through things so fast,” said Musker, “but there’s some funny tableau that — if you don’t allow the audience to see that picture — you lose something.”

6. Think of the nose. Musker recalled another lesson in visual communication from Nine Old Man Eric Larson, which he’s drawn on many times. Larson urged him to consider a character’s nose as “a graphic pointer that points to where your eye wants to go. So if someone is talking to someone, make sure that nose isn’t leading you in another direction.”

7. Storyboarding is the best path to directing. Musker pointed out that most of Disney’s directors — he and Clements included — have experience in this field. “Storyboarding is kind of like directing on paper,” he explained. “You’re picking where the camera is, you’re trying to put over acting, you’re trying to develop entertainment through a sense of pacing, clarity — all those things.”

8. Directing as a pair can be tough. These two manage through a clear division of labor. When writing, Musker tends to generate raw ideas and Clements polishes them into a draft script. When directing, they supervise different sequences, channeling the Disney tradition of “sequence directors”; Musker often takes comedy and action, Clements more dramatic or heartfelt scenes. Musker vents his emotions about the partnership by drawing caricatures of Clements. Crucially, Clements said, they always feel like they want to make the same picture, even when they disagree.

9. Learn to take criticism. Many artists, young and old, don’t want to hear constructive feedback, said Musker. “Look at your own work and try to get objective about it: what is weak about it?” Nowadays, the abundance of online resources and communities gives people unparalleled opportunities not only to get feedback, but to actively seek it out by putting their work out there.

10. School isn’t everything. “Almost everything I learned about animation, I did not learn at school,” said Musker, reflecting on his time at Calarts. He credits Larson with schooling him in the craft: “The change of shape, positive statements, the value of silhouettes … the idea of timing, character, observation.”

.png)