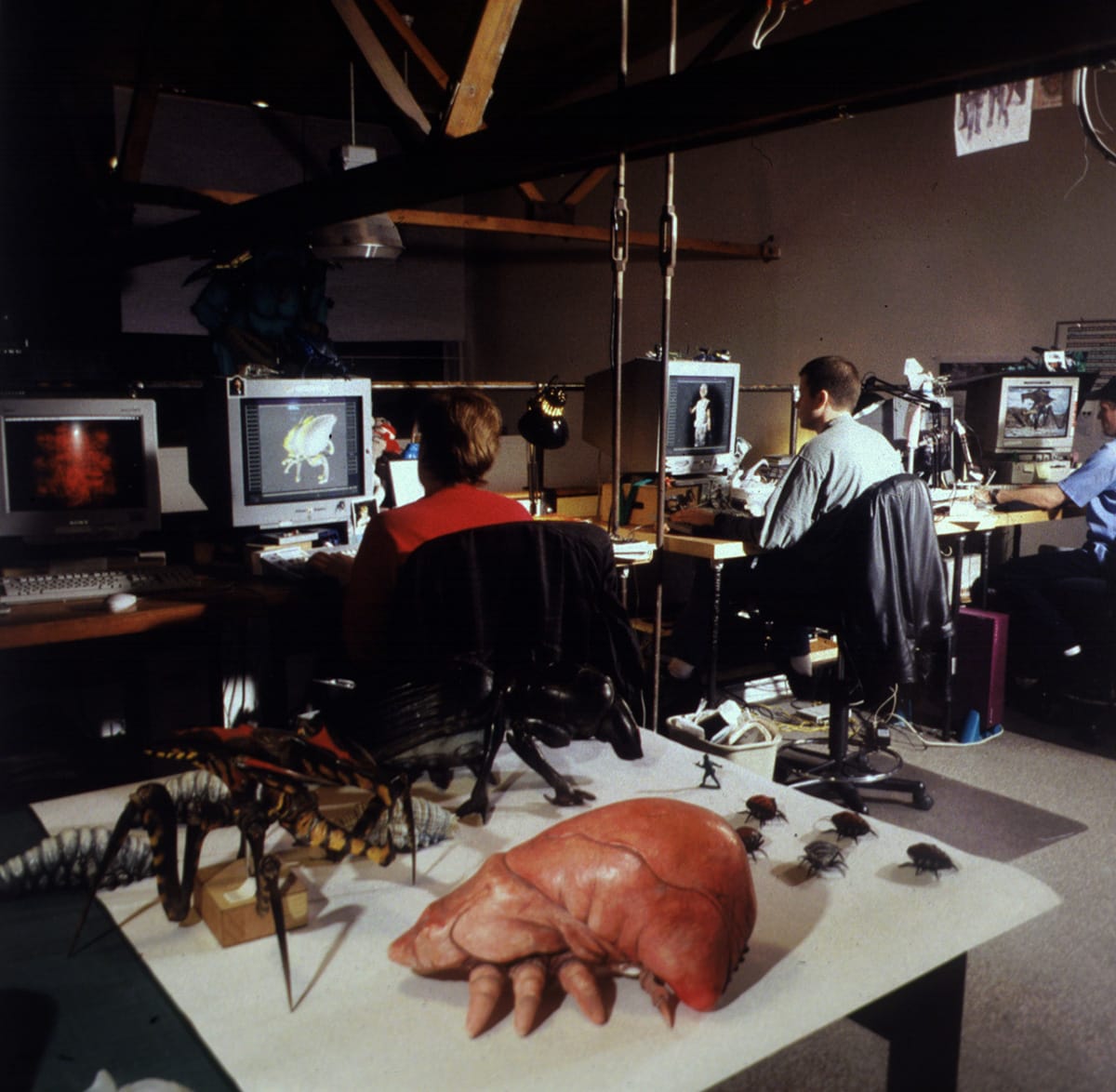

20-Year Anniversary: Creature Supervisor Phil Tippett Reflects On ‘Starship Troopers’

The career of Phil Tippett was famously laid bare during the making of Jurassic Park when his planned stop-motion animated dinosaurs were replaced with cg ones. But the visual effects supervisor quickly embraced the digital realm, continuing on the Spielberg movie and moving onto computer generated characters with Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers.

That film celebrates its 20th anniversary today. Although not a hit in its theatrical release, Starship Troopers remains a cult classic, fondly remembered for biting satire and just as much for a collection of grotesque bugs, which Tippett Studio played a big part in bringing to the screen.

Cartoon Brew sat down with Phil Tippett at his studio in Berkeley recently to revisit the making of the film, a discussion initiated by the unearthing of some old Starship Troopers location scout videos and on-set recordings previously thought lost. Segments of those videos are included in this Q&A. Tippett also goes into detail about how the film was originally greenlit, how he got his head around cg, and what he thinks about the state of visual effects today.

Cartoon Brew: In a New York Times article from 1997 about Starship Troopers, Paul Verhoeven was quoted as saying, “I stipulated in my contract that I would not do the movie if Phil wasn’t available.” He goes on to talk about the poetic realism of the creatures you were behind, and also your lifelong observation of the animals. How far did your history go back with Paul?

Phil Tippett: Well, I met Paul shortly after [producer] Jon Davison hired him for RoboCop, and Jon had gone out to every single director in the director’s guide book, and everybody refused it. Then he finally got down to ‘V,’ and sent it to Paul, and Paul refused it. Then his wife, Martine, I think, talked him into it. That’s where I met Paul for the first time, but I had been a big fan of the movies that he made in Holland. So I decided to work with him.

We did RoboCop, and then I got a call from Jon and went out to lunch with he and [director] Joe Dante, because they were developing something, with [screenwriter] Ed Neumeier, that was about soldiers fighting bugs on some alien planet. They went to Sony, and Sony said, ‘We’ll give you money to make a movie like this as long as it’s called Starship Troopers,’ because they had the property. It just went on from there.

There’s a famous test done for Starship Troopers [view below], and Paul Verhoeven introduces it. Was it a test done to convince the studio to make the film?

Phil Tippett: Yeah, that’s exactly what it was. We went out to Vasquez Rocks and shot Olympic gold medalist Mitch Gaylord playing a soldier that was being chased and killed by a bug. Then Jon and Ed and I – Paul was shooting Showgirls – we went to pitch it and it went up the food chain at Sony, and showed them what we were doing.

They would worry about things like, ‘Where’s the mouth on the bugs?’ We’d go, ‘It’s that little hole there.’ They’d be like, ‘Well, how do they eat?’ We’d say, ‘Well, they eat sap from the queen back in the cave.’ They’re like, ‘Really? But if they don’t have mouths, they can’t kill people.’ I go, ‘No, they’ve got these big beaks that can chop people in half, and they’ve got these things that can skewer them, so they just kill people. They don’t eat people. They don’t care about people.’

Then we had to go through the hierarchy of screening for three different executives, and at that time Mark Canton was the head of the studio. He brought his entourage in, and they looked at it, and he turned around and said, ‘Well, is this movie going to be fun?’ We’re like, ‘Yeah. Sure, it’ll be fun.’ So he said, ‘Okay, go ahead and make it.’

There are a lot of bugs in the film, how did you work out how each should be animated?

Phil Tippett: It all began with the overarching concept of, what are the bugs? We laid all that out in terms of ‘the simplest ideas are the best ideas,’ so working from the position of the genre, the war movie, we just attributed various warlike, mostly World War II-like, values to the bugs.

The warriors were the infantry, and then there’s a big tanker bug that’s like a flame throwing tank, and then there’s the hoppers, the Stuka dive bombers, and then there’s the king and his entourage and all that. How things actually move, you just empirically determine. We did a lot of research with documentaries on bugs and that kind of thing. Paul and I had a very similar world view and mindset, and we both like to do things that are very sharp and kind of staccato, and this lent itself to that.

Recently you discovered some old video that shows a scout for the film and some on-set footage. It’s fantastic to see that process. Can you describe the scouting side of things?

Phil Tippett: Generally what we did back then was, I used a Hi8 camera to go on location scouts. When we were scouting on location, I used it as a notebook. I’d just hold up the camera and put my hand in the shot and say, ‘The bugs are out here and they’re running towards us. They come up over this hill and they get blown up.’

I could send that to the vfx studio in Berkeley from Wyoming where we were shooting, and then the guys back at the studio can get a better sense of what’s going on. Then for the actual shots, each of the setups, various people on the art crew would document it. All the setups and all the takes, there was something like 15 hours of material, and it got lost for 10 or 15 years, and someone discovered it under their staircase. We digitized it all and then I cut that down to about 40 minutes worth of material.

You were involved in Jurassic Park which had gone from a stop-motion project to cg, and Starship Troopers came out in 1997, but there had been talks about doing this film maybe starting in 1994. What was your own cg education between Jurassic and the first test that was done for Troopers, and how did you ramp up the studio to deal with cg?

Phil Tippett: There was really no other alternative to it. Both of those jobs just landed in my lap because there weren’t that many people that were doing that kind of stuff, so I never really had to know anything about computers. I gave it a shot once, and there was just too much information in the manual to do it. It’s just that the process is kind of antithetical to … I would go mad if I had to sit in front of the computer all day.

What I’m required to do, really all I need to know, is the basic principles of what you can do and what you can’t do, and what’s difficult and what’s not difficult. Most of my stuff is more in shaping the thing in pre-production with the team, with the director and DP [director of photography], and then going on location and making sure all that stuff is going to work, and then coming back and putting it together.

One of the bridges between stop-motion and cg was the Dinosaur Input Device or Digital Input Device (DID), which was made for Jurassic Park, but also used on Troopers. Can you talk about how that came into play?

Phil Tippett: Well, at that point in time, it was very hard to find good computer graphics animators. Pretty much all of the animators on Jurassic Park were Canadian, because they had schools that taught computer graphics there, but they had only done stuff like the so-called classic Disney animation, more cartoony squash and stretch type stuff, Pixar-y type stuff, and a lot of flying logos. But these kinds of things require a different kind of a mindset.

You’ve got to get a lot of things right, and so since there weren’t enough computer graphics animators, they put out a cattle call for stop-motion people. We put together a bug armature – [visual effects supervisor] Craig Hayes was a big part of that. It was just steel, and put him on the stage and just shot tests. Then I just picked two or three of the best ones, and then we duplicated the DID design, but configured like a bug.

Despite all the great cg work in the film, there’s still a very practical feel to it, either from practical bug pieces that were made, dummies that were used, or explosions on set. What do you remember about that mix of practical and digital?

Phil Tippett: We let the script and the needs of the script drive everything. Jon and I and Paul were big fans of mixing and matching practical stuff with the post-production stuff. We’d just get together and go over the script and storyboards, and say, ‘For this reason, all these need to be computer graphics, and for these other reasons, Amalgamated Dynamics was going to build those.’ Most of that centered around contact, like when you actually see a real person about to be chopped in half and the beak of a bug. That was a real human until the chomp happens, and then that’s a computer graphics thing, but you want to keep the computer graphics people off screen as much as possible, because they don’t look so good.

What direction were you, and Paul, giving the animators in general terms for the bug behavior?

Phil Tippett: All that stuff was laid out in the script and refined in the storyboards, and then there would be certain logistical things that would lend themselves to a more practical way of doing things, like the first time you see the bugs when the camera booms up over the wall of the fort, and you see this horde of bugs. Paul, in the storyboards and talking about it, said, ‘They’re just swarming everywhere. They’re like ants. They’re just climbing over the hills.’

When you get to the location and you look at it, and you go, ‘Well, the bugs wouldn’t do that. They would take the path of least resistance.’ That was laid out in the geology of the landscape, and so the bugs go where the water would go. They flow that way, so you get this kind of back up. There’s actually kind of an intelligence or a logic behind what they’re doing, but it’s kind of an unconscious thing.

This had to be one of Tippett’s biggest digital shows – how did the production go in post? Did it go smoothly? What was most challenging?

Phil Tippett: I think the worst part was realizing the enormity of the thing. In Jurassic Park, there was something like 50 shots, and we ended up doing 250 shots in Troopers. That was really daunting. One night I had a dream, and in the dream I had an 18-foot piece of bamboo, thick bamboo. On each end of the bamboo was a macramé seat, and Jon Davison got in one seat, and Laura Buff, the visual effects producer on the studio side, got in the other seat. I got in the middle, and I had to walk them up a very tiny path that went thousands of feet up over a sheer drop into the ocean. Then the path took a 90 degree turn, and it was like, ‘I don’t think I can manage it.’ Because I have a horrible fear of heights. Then the idea just dawned on me. It’s just like putting one foot in front of the other. Don’t think about anything else. I woke up and went, ‘Thank you, Lord.’

The film has definitely acquired a huge following, but do you think people missed the point of Starship Troopers when it was first released?

Phil Tippett: A lot of people totally missed the point, including us, because Jon Davison called me on opening weekend and said, ‘We tanked.’ He was like, ‘We only made 15 million dollars.’ We were like, ‘What do you think happened?’ He said, ‘What happened was we made an R-rated movie for kids, and they couldn’t get in.’ What was interesting about that, though, was we opened up against Mr. Bean, and Mr. Bean was the box office champ that weekend. We figured that was because all the kids were buying Mr. Bean tickets and sneaking into Starship Troopers.

Did you feel like it actually would have this extra life on vhs and then dvd?

Phil Tippett: I had my suspicions. In fact, after Starship Troopers, Paul was interviewed in Artforum. Ten critics had their best ten things that happened during the year, and almost all of them had placed Starship Troopers really high. Paul in that article, quoted me. He said, ‘Phil Tippett said that, ‘Paul, after this, no one will ever give us 120 million dollars to make an art film.’

That’s kind of what happened, because that’s how Paul approaches these things nowadays. Everybody hopes they’re going to make money, and I think that was the lag in the public perception of this stuff – sometimes those kind of ideas or experiences just take time to settle on people.

You directed the sequel to Starship Troopers. How did that come about?

Phil Tippett: That was Jon Davison’s idea. He said, ‘Okay, you’ve got to direct something.’ We went into TriStar and pitched doing a direct-to-dvd thing for about five-and-a-half million bucks, and it went back and forth. The studio wanted it to be Starship Troopers, and we just said, ‘Our approach is we can’t make a big spectacle war movie for five million bucks, but we can make a horror movie. If Starship Troopers was Aliens, this is going to be Alien. It’s going to be like Ten Little Indians in a haunted house.’ Bang. They bought into that.

On Reddit a few years ago, on one of those Ask Me Anything sessions, you talked about the way that people approach visual effects iterations these days. You mentioned something where it’s become, ‘Find what’s wrong with this shot.’ Someone re-posted that on Twitter recently, and it really blew up, perhaps mostly from visual effects artists who totally feel that pain. Can you elaborate on that comment?

Phil Tippett: That was more of a product of, well, stuff like that did not happen until the whole franchise thing went mad. Then everything became like everything else, more corporate in terms of interference by people that don’t know anything, but have to justify their miserable existences by saying stuff so that they’re ‘present.’ That’s just the way it is everywhere.

You know, we had to plead with George Lucas to do the retakes on things in Star Wars. He was, ‘No, it’s fine.’ And we were like, ‘No, please. Let me do it. I can do it better.’ And it was then, ‘Okay, you can do one more take.’ I was talking to [ILM visual effects supervisor] Dennis Muren about it a while back, and he went, ‘Yeah, it’s just we never talked about what was ‘wrong’ with the shot. You could see what was wrong with the shot. You didn’t need to talk about it, you just had to fix it.’ All we did was try and think of what would make it better, what would be more fun.

How are visual effects different now? It seems sometimes there are such long shots with cg creatures in them, and you see everything, whereas in the ‘old days’ things were much more hidden, sometimes by design because there were wires and things hanging out of them.

Phil Tippett: Well, again, I think it was Dennis Muren who mentioned, when Saving Private Ryan had come out, he said, ‘The mindset of the filmmakers in both Private Ryan and Troopers was the same.’ In a lot of ways, they were. Just by its very nature, Troopers is an action film, so there’s going to be more cuts, but you look at World War II footage, and there’s not a lot of long takes. People are ducking bullets.

It’s just both those pictures had this visceral war kind of thing going on, and on top of that, one of the aspects of the design that we wanted for the bugs, specifically those warrior bugs, was that they had a certain level of abstraction.

The first time you’re really going to get to see them for any length of time is at night, and they’re dark, and so your first visceral contact with these things is like, ‘What is that?’ I think that adds to the anticipation, and then the horror if you can’t grab onto something right away. You have to get to know it.

.png)