‘If You Were Into Freak Jazz, You’d Know’: Director Julian Glander Breaks Down A Key Scene From ‘Boys Go To Jupiter’ (EXCLUSIVE)

Julian Glander’s debut feature, Boys Go to Jupiter, extends his signature CG stylings into a capacious, dreamlike narrative space, and the result is as texturally rich as it is emotionally offbeat.

The film expands the pastel surrealism of Glander’s shorts into a 90-minute, sun-baked diorama where adolescent drift, speculative science, and musical whimsy coexist. Built almost entirely in Blender and populated by a cast of comedians and musicians who intuitively sync with its tone, the film is part linear coming-of-age tale and part environmental mood piece.

For this article, Glander walks us through a key scene to illuminate how his graphic instincts, multi-disciplinary approach, and playful animation process converge on screen. His breakdown reveals the film’s deeper architecture, built with tools that allowed Glander to realize the project on a shoestring budget lean enough to qualify for its recent Independent Spirit Award nomination for the John Cassavetes Award.

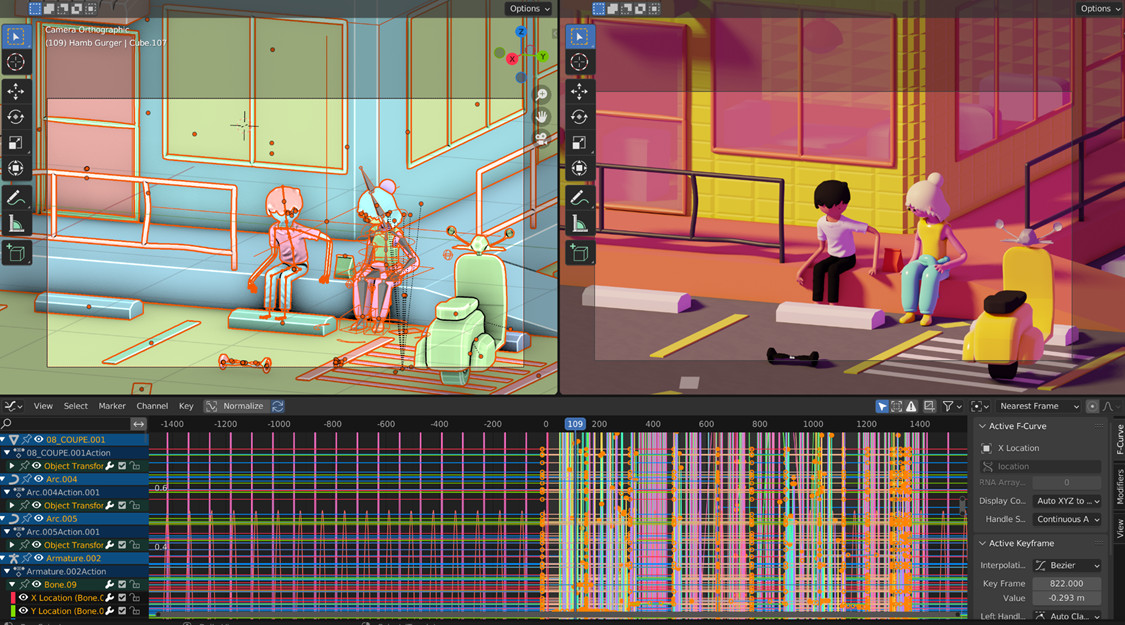

Julian Glander: This is a pivotal scene in Boys Go to Jupiter, where our hero, teenage delivery driver Billy 5000, has a philosophical conversation with Rozebud, an older girl he vaguely knows from school. Billy is trying to figure out if he’s in love with Rozebud or if he just wants to be her, as they share a stolen novelty food item called the Pancake Burger. He’s also asking her for a job. It all folds into his bigger arc: trying to find an identity and a place in this suburban Floridian hellscape.

We recorded the character voiceover with Miya Folick and Jack Corbett and really let those performances dictate how the scene looks and feels. What I loved about working on this movie was that, because we self-financed and self-produced, we didn’t have to follow any traditional pipeline and could make adjustments based on what felt good.

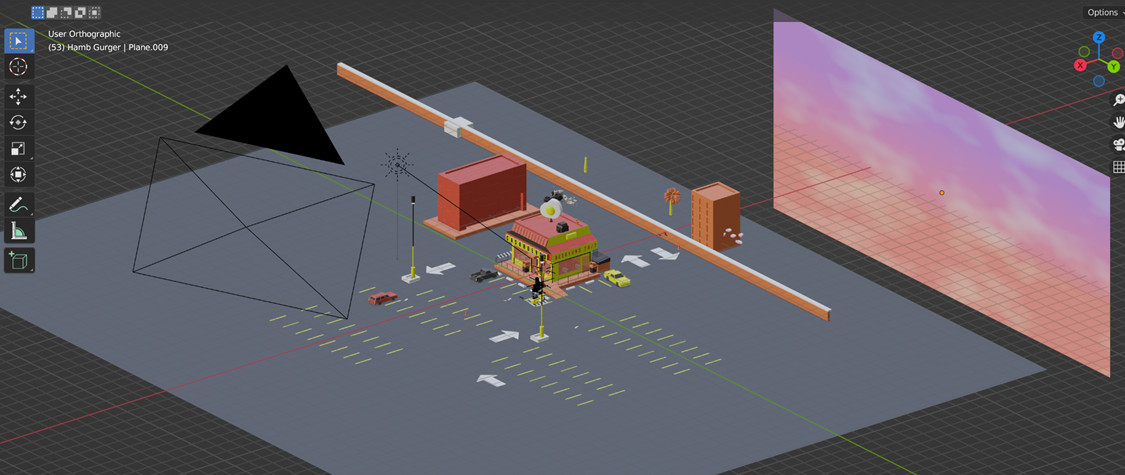

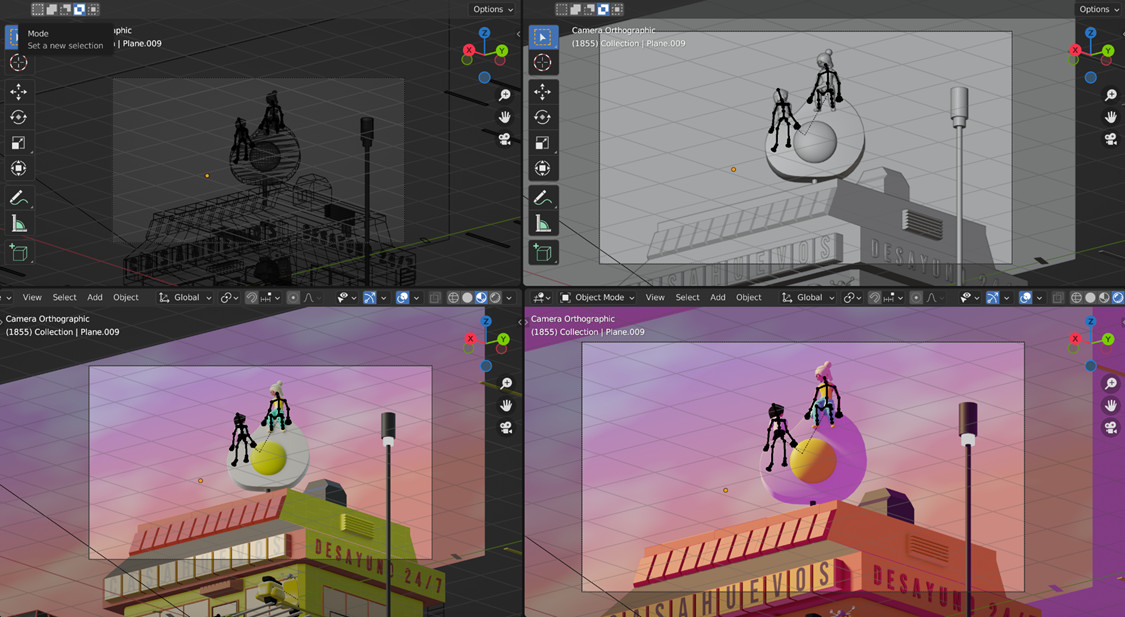

We used Blender 3.3.1 for the whole production and assembled the movie in Final Cut Pro. Most of the scenes are constructed to be viewed from one angle. Think of them as stage setups, postcards, or shoebox dioramas. It probably comes from my background in illustration, where sometimes a ton of information has to be instantly clear and readable. As I’m building a scene, I’m making sure that all of the key props are visible. This keeps production organized, but more importantly, it’s helpful for the viewer—you always know where you are in relation to the rest of the scene, without the disorientation that comes with a lot of cutting and moving.

Here’s some early art, before I had nailed down the color scheme and character design. In this draft, Billy rides around town on a bike, which I swapped out for his iconic hoverboard.

We return to the Casahuevos breakfast restaurant a few times in the movie, but each time it’s a little different. A change in lighting, weather, or time of day can make it feel like a whole new set.

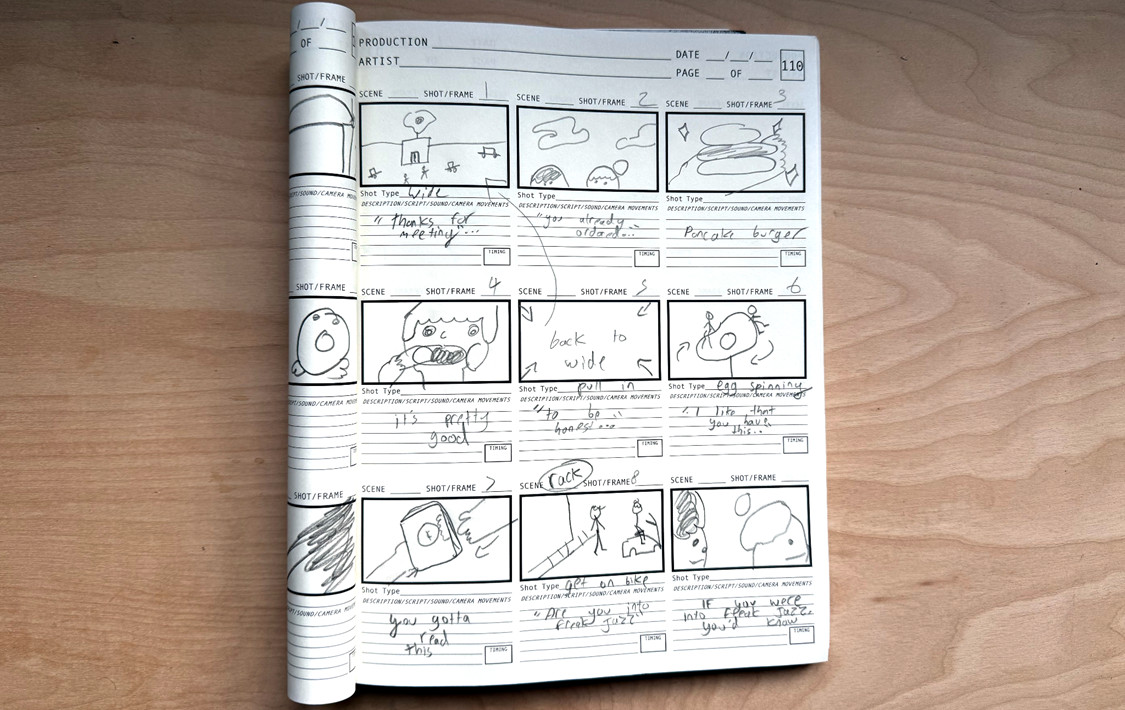

I’m not a huge storyboard person. There’s a type of big-budget animation that’s fully dependent on being faithful to storyboards, and it doesn’t leave room for new ideas further down the road. When a movie costs a billion dollars to make, you probably have to do it that way, but because we had such a small team, we could take a more open-ended approach. That said, I did make thumbnail boards for a lot of scenes. I call them “same-day boards”—they are used to keep track of what shots I need to generate so it’s not all in my head. But if I look at them even a day or two later, they make no sense. The goal isn’t to figure everything out; it’s just to get a sense of what shot setups I need to build in Blender. You can always go back and add inserts and reaction shots, but to me there is an art to doing a scene with as few cuts as possible.

This whole sequence consists of 16 shots across two and a half minutes, which is pretty on par with the cutting speed of the movie. It’s a much lower shots-per-minute average than most films, animated or otherwise, and I really like the way it feels. So much of the appeal of the film is in its tone and texture. When we let the shots linger, we can sit in the world, get comfortable, and soak in the atmosphere. Some of my favorite scenes in Boys Go to Jupiter are uninterrupted wide shots that play out for an entire minute or longer.

The camera work in Boys Go to Jupiter follows some pretty basic guidelines: almost always isometric, almost always with the tripod on the ground. I wanted the footage to feel almost documentary-style, as much as was possible for an animated film. We save the rack-focus effect for a few key moments with Rozebud. From Billy’s POV, she’s so dreamy and unreal, and maybe as a result, he’s not seeing her as a full person.

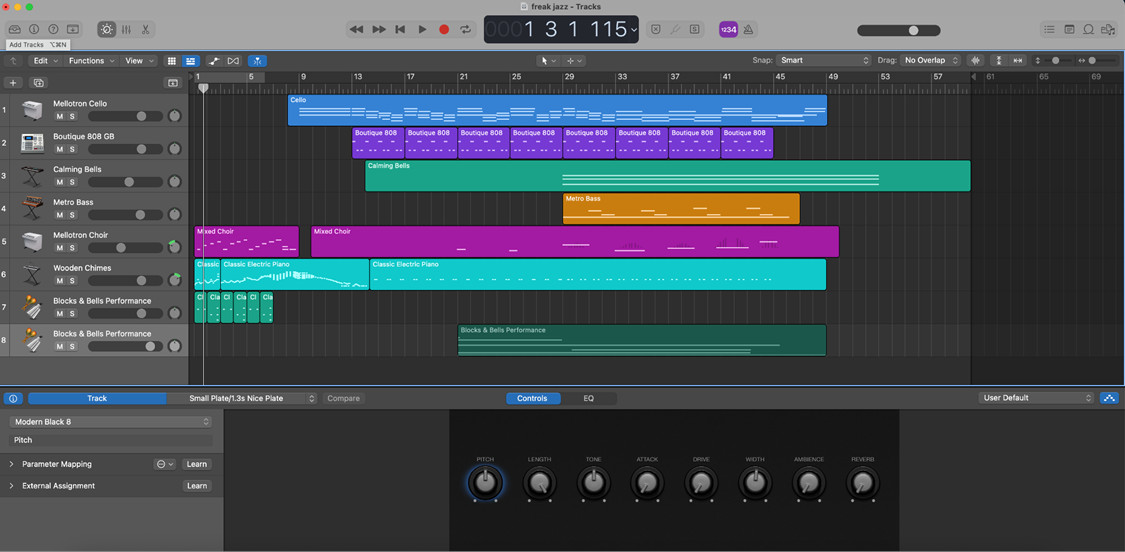

I was writing and producing the music in Logic at the same time as I was animating the film. To amplify the dreaminess and memory-like qualities of the story, the soundtrack has a hazy, distant quality, with a lot of soft bell tones. I hear it as the sound of an ice cream truck that’s driving farther and farther away. Perhaps not coincidentally, a lot of the music ended up sounding like the music I really liked in high school. Because Rozebud is always surrounded by a swarm of bees—my version of a Disney princess with little birds and forest creatures all around her—there’s also often a buzzy synth hum in scenes with her.

The conversation my producer Peisin and I kept having was: we have to be so economical about what we choose to animate and how we animate it. At our budget and scale, we’ll never finish the movie if we try to make it look like every other expensive CGI movie. That doesn’t mean it has to be worse or cheaper-looking; it just means we have to find ways to make it look different and use our limitations to our advantage. Sometimes the story demanded complicated character actions and movements, and we really invested in those. Other times it was okay for that to happen between cuts. For instance: do we really need to see Billy and Rozebud climbing this fire escape ladder to get to the roof of the building? Climbing, staircases, and ladders are some of my least favorite things to animate. So the movement happens between shots. But the dialogue is leading you through the scene, so that jump cut doesn’t feel jarring. It’s actually kind of beautiful and fresh, like something you’d see in live action.

It’s a treat to “find” a shot in the 3D viewport—you never know what cool surprises you will end up with. The spinning egg is my favorite shot in the movie. It’s so instant, and the spinning of the egg emphasizes this delicate dance that Billy and Rozebud are doing—always circling each other, with Rozebud trying to keep the high ground. It is mandatory for every coming-of-age story to have two characters sitting on a rooftop.

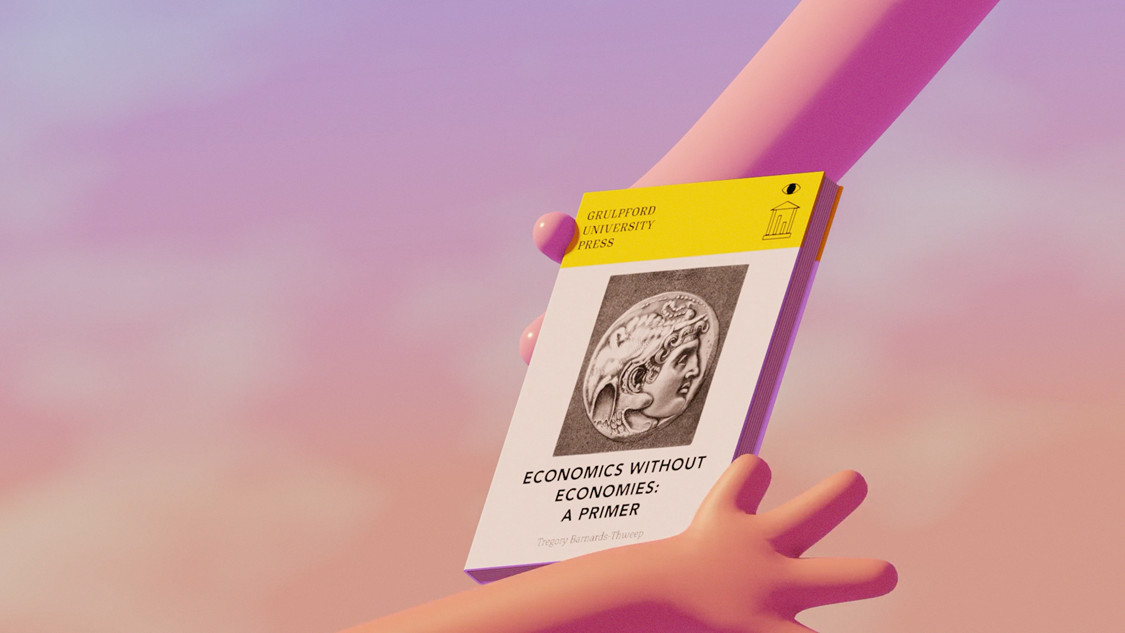

Asset flip alert: the book is a prop from my previous short film, Tennis Ball On His Day Off. Cinematic universe?

This was pretty risky: when we got into the booth with Jack Corbett, I didn’t know what was going to happen in this scene. In the script, it just says “musical landscape sequence.” I wanted to leave space to figure it out later.

Talking with Jack, we decided it made sense for Billy to read some dense economic theory that played into the wider themes of the movie. Together we wrote this passage about “the ants and the snails,” which turned out really great. My direction for Jack was to read the passage like he’s been called on in class and he’s reading the words for the first time. That’s a surprisingly challenging voice-acting note, but he crushed it.

The most exciting sequences to work on were the ones where the visuals don’t have to have a 1:1 correlation with what’s happening in the audio. So much of the story is delivered through dialogue, which means the action onscreen doesn’t have to be redundant. The text here is very dense, so it felt like a good moment for something breezy and beautiful. I was thinking about Gwen Stefani’s music video for “Cool,” where they’re riding mopeds on the Italian coast. It’s the definition of romantic.

And then we pull out into this super-wide shot of the whole landscape. This one ended up being a big labor investment—within Blender, I developed a dynamic road system so we could have dozens of moving cars and headlights creating a sort of glittering effect on the map. In the context of Boys Go to Jupiter, it’s the moment where Billy is starting to understand how big the world is around him and how small he is in comparison. This is what we save the big camera moves for.

.png)