The Left Front: Radical Art in the 1930s ‘Red Decade’

Politically-conscious graphic art has a long history, from Daumier up to Lynd Ward and Eric Drooker. The 1930s and ’40s were a rich period in this respect, as the rise of Communism and Fascism coupled with the Great Depression brought issues of social justice to the fore. The John Reed Club, an organization founded by staff members of the Communist magazine New Masses, formed in 1929 to support leftist artists and writers. It allied with the American Communist Party, and spread to thirty chapters nationwide before it was replaced in 1936 by the American Artists’ Congress, which survived until the Second World War.

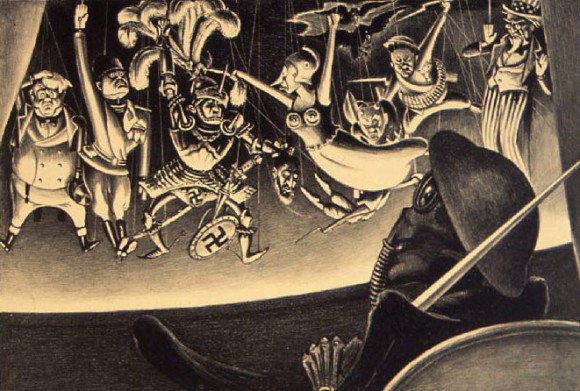

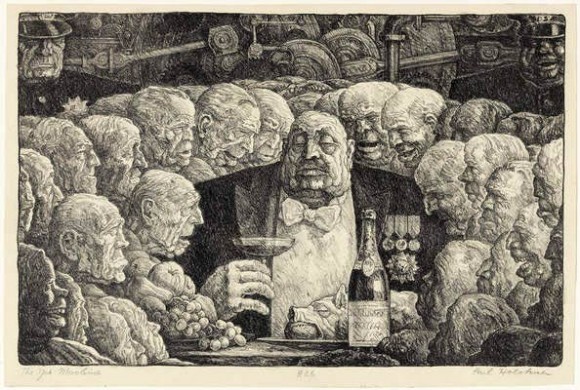

The Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, has mounted “The Left Front: Radical Art in the ‘Red Decade,’ 1929–1940,” an exhibition of artists who showed with the John Reed Club and the American Artists’ Congress. Drawn from the Block’s collection and elsewhere, the show naturally features artists from the Midwest, among more famous names. Some of the lesser-known works holds their own: Mabel Dwight’s “Danse Macabre” (1933-34, above) with its vaudeville show of political caricatures, and Carl Hoeckner’s “The Yes Machine” (1935, below), a scathing look at the capitalist fat cat. Among the famous fine artists included are Rockwell Kent, Stuart Davis, and Raphael Soyer. Diego Rivera, who made such a bad impression on Club members when he addressed them in 1932 that they repudiated him, is represented by his 1934 book, “Portrait of America.”

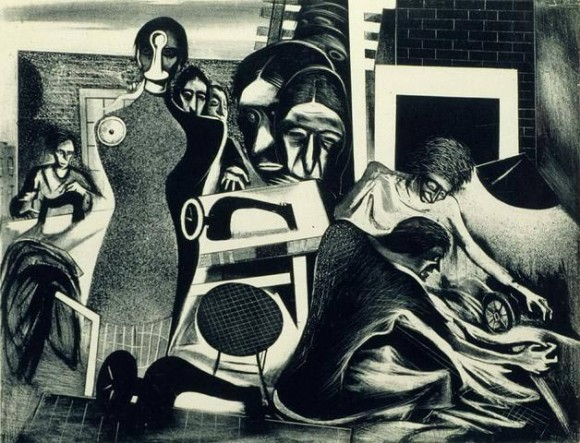

Artists who worked in cartooning and animation are also represented. William Gropper, who helped found New Masses, produced many paintings and cartoons on social themes, and is represented by several lithographs. Boris Gorelick has three lithographs, including his brilliant, Cubist/Surrealist-inflected work, “Sweatshop” (1938, pictured below). Gorelick’s career as a background artist in animated films spanned decades, including UPA’s Brotherhood of Man (1945), Friz Freleng’s Oscar-winner Birds Anonymous (1957), and television work on The Alvin Show and the animated Star Trek.

In a 1964 interview, Gorelick summed up the decade of the 1930s: “There was ferment; there was curiosity; there was agitation; there was activity; there was interest, and there was freedom of thought.” When the U.S. government-sponsord Works Progress Administration (WPA) began combating the Depression by commissioning artwork, Gorelick joined and helped bring other artists, like Gropper and fellow John Reed Club member Harry Sternberg, into WPA programs. Artists with leftist politics would never be quite so welcome on the government payroll again. Gropper was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1953; he pled the Fifth and was blacklisted.

Co-curators (and Northwestern doctoral candidates) John Murphy and Jill Bugajski have done a fine job of scholarship and, I hope, started the ball rolling for future studies of the period. There remain tantalizing avenues to explore: Isadore (Izzy) Klein, a long-time animator and writer, credited with helping to create that protector of the proletariat, Mighty Mouse, was part of the group that started the John Reed Club; or Otto Soglow, who exhibited work in two John Reed Club-organized exhibitions in New York in 1930 and 1932, just as he was inventing The Little King. Caricature and exaggeration run like threads through print cartoons, animated films, fine art, and illustration, from long past to the present minute.

With over one hundred works, “The Left Front” is the largest and most comprehensive exhibition to examine this facet of political art, though, as you can see from the omissions, there’s room for more research. The exhibition runs until June 22.

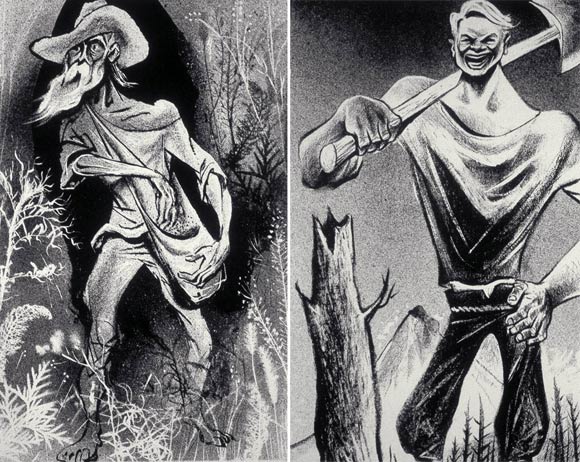

(above: Johnny Appleseed and Paul Bunyan from the series “American Folk Heroes” by William Gropper)

(above: Johnny Appleseed and Paul Bunyan from the series “American Folk Heroes” by William Gropper)

.png)