‘Original One-Off Pieces… Are Really The Only Thing I Want To Make’: Inside Adult Swim’s ‘The Elephant’ With Patrick McHale, Pendleton Ward

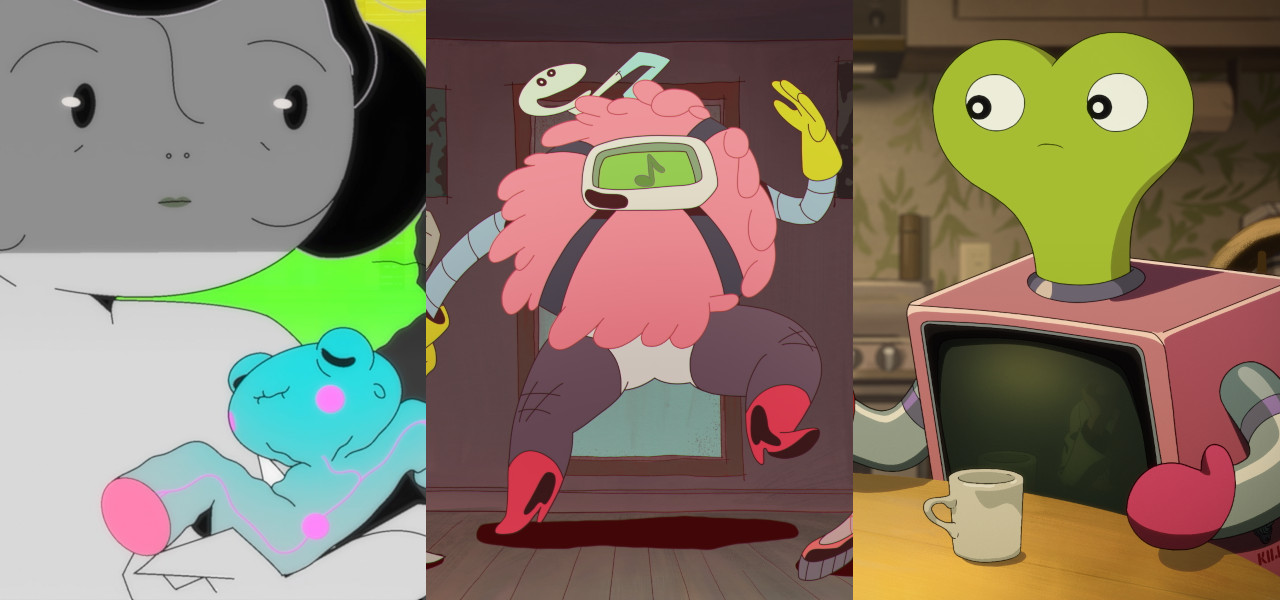

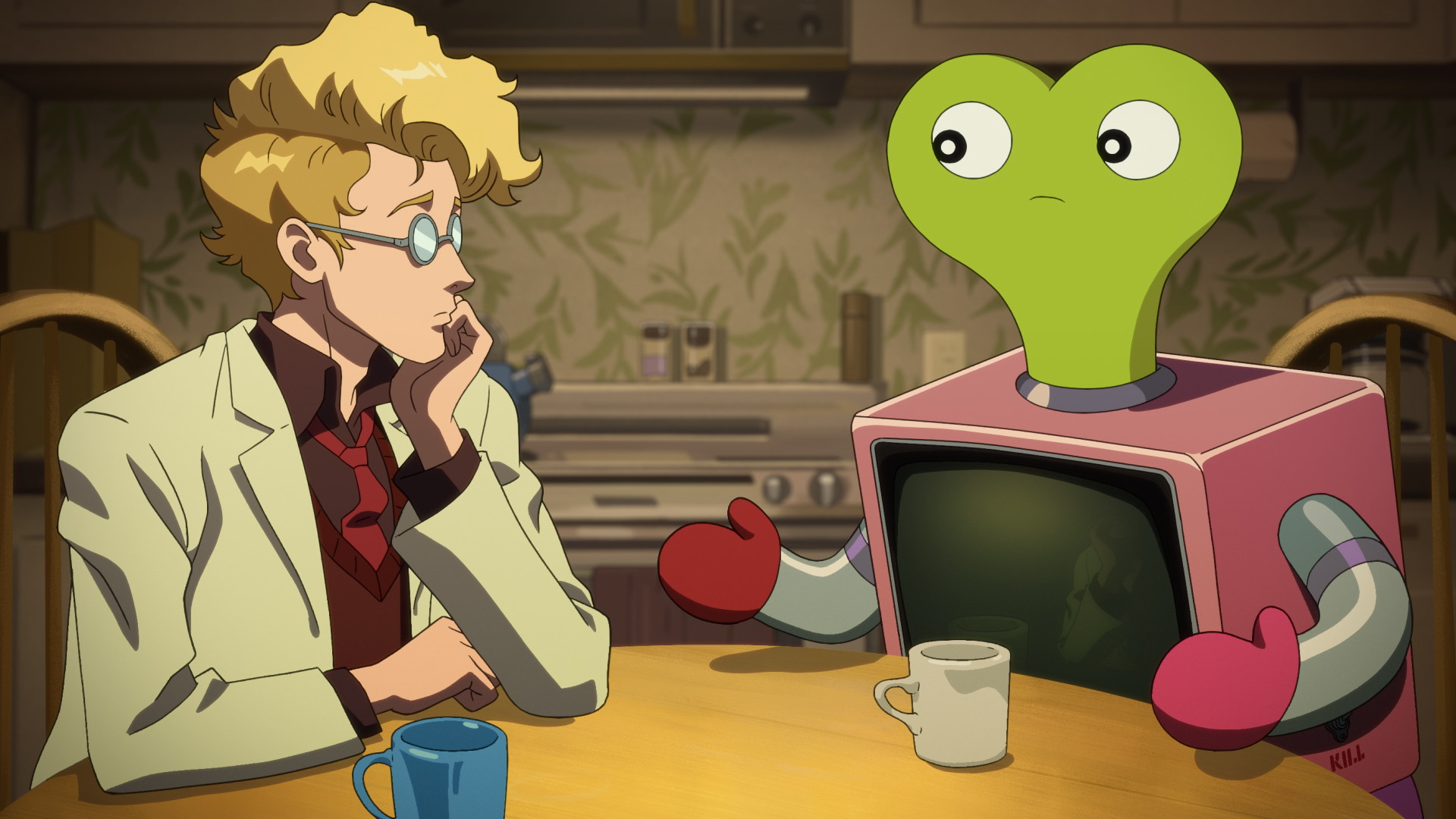

Adult Swim’s The Elephant is not a project that lends itself to easy explanation. Designed as a three-act animated experiment created largely in isolation, the special brings together Cartoon Network legends Patrick McHale (Over the Garden Wall), Pendleton Ward (Adventure Time), Rebecca Sugar (Steven Universe), and Ian Jones-Quartey (O.K. KO.! Let’s Be Heroes) for a rare collaborative, one-off exercise.

Rather than building toward canon or continuity, the project is defined by its limited nature and the deliberate lack of shared knowledge between its creators.

For McHale, that premise meant everything. Asked about the importance of non-canon, standalone work, he tells Cartoon Brew it’s “the most important thing. Original one-off pieces of work are really the only thing I want to make. It’s just hard to get those funded.”

Ward shares a similar sentiment, explaining, “This is a very rare, cool thing that happens in animation like once every, you know, five years or something, where you get to do something very experimental,” he says. “So everyone involved is very aware of that and very appreciative of the experience.”

From the outset, both creators understood that where they landed within the three-act structure would shape how they worked. McHale was clear about his preferences early on. “I knew that I shouldn’t do the first segment, because I’ve never been confident about starting with a bang and hooking audiences from the jump,” he says. “So I campaigned to do either the 2nd or 3rd act.”

Ward, meanwhile, found himself at the opposite end of the spectrum. “We all agreed in the beginning when the directors got together to discuss what we were going to do,” he says. “That was one of the things that we all picked, an act.” In his case, that meant opening the special. “I got the first.”

Ward describes the experience of beginning The Elephant as unsettling. “Everyone was stressed out about how to approach this, because it’s so difficult to write anything where you can’t set up anything,” he says. “You don’t know what’s coming before. It’s so hard to begin.” At one point, he recalls admitting as much directly. “I remember on an e-mail chain, I was like, ‘I’m freaking out. I don’t know what to do.’”

The advice that helped him move forward came from McHale, and it was intentionally minimal. “I remember Pat said something like, ‘The beginnings are beginnings,’” Ward says. “He just gave me the idea that it was beginning vibes.” That idea became Ward’s anchor. “That’s all I understood. So, my character is very new to the world and innocent in that way, and discovering things for the first time.”

McHale, meanwhile, was grappling with the opposite problem. Knowing he would close the special fundamentally shaped his process. “It certainly impacted how I approached the project,” he says. “I felt a lot of pressure to make the end come together so that audiences didn’t feel like we’d completely wasted their time.” The stakes, he notes, feel higher at the end of a longer piece. “If they’re watching a 20-something-minute film, the ending better make it feel worth it. So I felt a lot of pressure.”

That pressure was compounded by how little context he had. Writing a final act without knowing what preceded it is not a standard storytelling exercise. “It’s really hard to write the third act of a story that you know almost nothing about,” McHale says. “Really hard. Maybe it would be easier for other people, but it was really hard for me.”

Both creators ultimately responded to that uncertainty by leaning into collaboration rather than control. McHale describes approaching his segment visually without a fixed blueprint.

“Without giving too much away, I wanted to make visual choices that would both complement and contrast well with what I imagined Ian, Rebecca, and Pen might be doing… though of course I had no idea what they were actually doing,” he says. Instead of dictating a single aesthetic, he let people drive the work. “The aesthetics of my segment mostly came from choosing people I wanted to work with and letting them do their thing.”

Ward echoes that instinct. “Really, all I was doing was having fun,” he says. “I was just like, what do you all want to do? What should we, that’s usually how I approach it.” For him, the process was as much about creating space for collaborators as it was about defining a look or tone. “It was really cool to be involved and to work with Rudo [Argentina], the animation studio that I worked with,” he says. “I had seen their work online, and I loved it. It’s beautiful.”

He was also quick to praise the input and support of art director Beto Irigoyen and animation director Patricio Bauzá.

For McHale, that openness represented a meaningful departure from his usual way of working. “I generally like to be in complete control over a film I’m directing, to really understand it inside and out in order to make strong informed decisions,” he says. “But this project forced me to give up on some of that perfectionism.”

When the pieces finally came together, Ward says the individuality of each creator remained visible, even within the shared framework. “Fingerprints is a good word,” he says. “You can see everyone’s influence in any one panel, in one frame.”

In the end, The Elephant does not resolve into a neat and tidy cartoon, but rather a collage of creator fingerprints, influences, and hints at how they interpret the work of their contemporaries.

It is a project shaped by beginnings that don’t know their endings and endings written without knowledge of their beginnings. For McHale and Ward, that tension is not something to smooth over, but something to be celebrated.

.png)