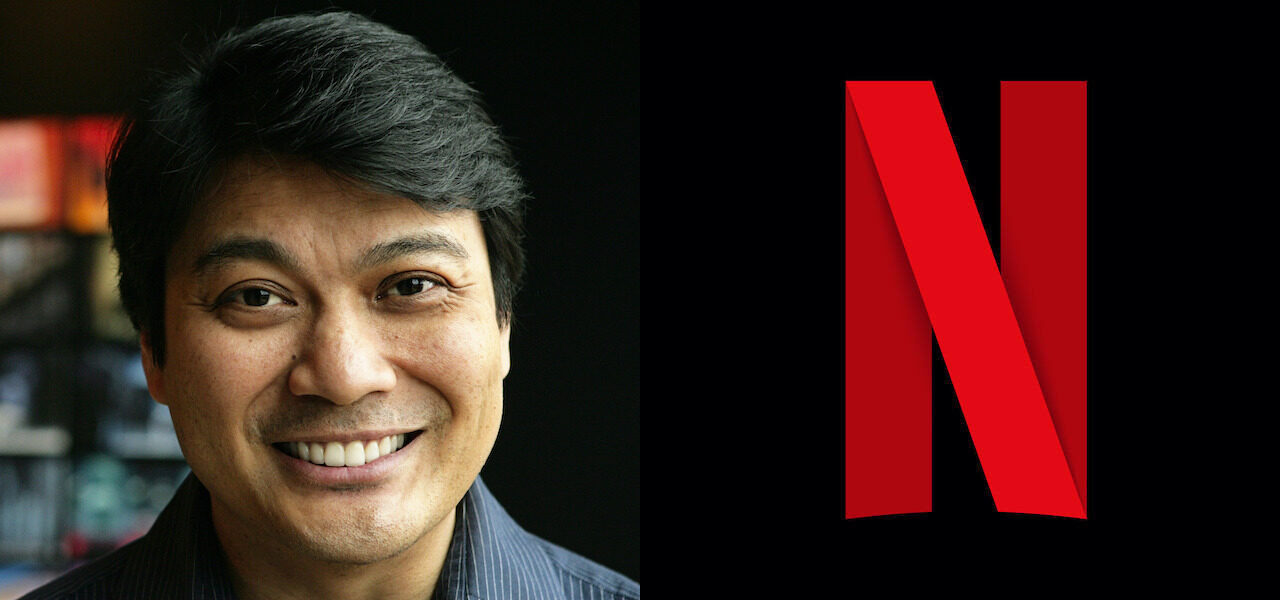

Exclusive: Ronnie Del Carmen, Co-Director Of ‘Inside Out,’ Is Developing An Animated Feature At Netflix

Ronnie del Carmen, the Oscar-nominated filmmaker and Pixar story veteran, has moved to Netflix. He is writing and developing an original animated feature as part of an exclusive overall deal with the streamer, Cartoon Brew can exclusively reveal.

The feature, which del Carmen plans to direct, will be rooted in the lore and mythology of the Philippines, his home country. The deal covers animated series as well as films, and he will also consult on other animated projects at the streaming giant.

Del Carmen got started in the film industry as a painter on the set of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, which was shooting in the Philippines. Arriving in the U.S. in 1989, he worked as a storyboard artist and character designer on Warner Bros. Animation’s Batman: The Animated Series, then directed on the studio’s series Freakazoid!.

Moving on to Dreamworks, then Pixar, del Carmen held a variety of story and writing roles on features including The Prince of Egypt, Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron, Finding Nemo, Up, Coco, and Toy Story 4. He was co-director on Inside Out, on which he also has a story credit; the film earned him an Oscar nomination for best original screenplay.

Having approached storytelling in animation from every angle, del Carmen tells a new story below: that of his own path. He speaks to us about the milestones in his career and the lessons he learned along the way.

One of del Carmen’s first jobs in the industry was as a storyboard artist on Batman: The Animated Series. He recalls being hired by the show’s co-creator Bruce Timm:

In 1991, I landed the gig at Batman: The Animated Series when they were not looking for people. They had a couple of episodes in the can already and a full crew. Bruce Timm saw my portfolio, which had a few samples of animation work I did for DIC [Entertainment] — all two and half months of animation experience — laced with a few samples of storyboard art I did from scripts I bought at Book City in Burbank. Loved buying scripts. Tv episodes of China Beach were my favorite. So I boarded a snippet of one of those.

I had no chance here, you have to understand. The animation shops in town had all crewed up. Especially true for Batman, which was the most coveted show: anyone back then would chop off their left pinky for a spot. Then Bruce asked what I wanted to do. I mumbled, “Character design?” He did not falter: “No. You’ll do storyboards.” And that was it.

I learned cinematic language, dramatic staging and lighting, counting frames and the rudiments of an x-sheet. Dick Sebast coached me patiently, Glen Murakami and I canoodle over comics and design, but most of all I imprint with Bruce. He was a man who had a north star guiding him. He was an individual forging a show in his own image. I had no idea this was the big lesson staring me in the face. Bruce made his work and what he was into the work of his life.

Later in the decade, del Carmen joined the recently formed Dreamworks as a story supervisor on The Prince of Egypt — his introduction to feature animation. Early on, he “bombed” a sequence in which Moses pleads with his adoptive brother Rameses in the hope of avoiding the Ten Plagues. He later had a second chance at it, as he explains:

I used the art department location to stage the sequence: a gallery of giant statues of the Egyptian gods sitting in a row. I placed Rameses up there on the lap of one of the gods. I was remembering my childhood in the Philippines when my younger brother Rick and I would sneak out of the house after lunch. Soon we both hear our mom yell our names out loud. She’s on to us and we’re in trouble. But she does not look up to see us in the tree. We were getting away with something!

I imagined this story for Rameses and Moses as kids hiding from Seti and the priests. When Moses enters the palace as an adult, no one in the royal court can find Rameses. But Moses knows where he is. He enters the gallery and starts to talk to the giant statues. Rameses is sitting up there. When Rameses needs to get away from responsibility, he sits up there on the lap of the gods. That was where they both hid as kids. They reconnect as brothers.

When I showed this to Brenda [Chapman and the other] directors, they were so excited. I told them where the idea came from. Brenda complimented me and I felt that I had crossed a threshold. After that day, I started to understand what the job was. I wasn’t there to draw. It’s true that in this visual medium, drawing was a way of telling a story — but the story has to ring true to an audience to begin with. It has to come from you.

Del Carmen’s first gig at Pixar was as a story supervisor on Finding Nemo. The studio was not as he expected:

Pixar was such a culture shock. I discovered they did things differently here. There were no producers present half the time. Back at Dreamworks, there were wall-to-wall producers who called the shots. Here at Pixar, it was the director. What notions he had that day or what he’s keen on doing — well, he just did it. [On Finding Nemo, director Andrew Stanton] was writing the entire movie himself, too; he took on the great Bob Peterson in the ensuing reels to help write. It felt lawless.

Also, Andrew convened the story crew all the time. He stayed in there and worked on the movie with us. We were all writing and solving problems that he was facing with the story. We would solve the funny, the action, the drama — all of it. In there this was chaos. It was volatile. It was crazy and unhinged. I was not understanding this, but this is the way they run things here. When the first reels was finished we had a screening. We watched our work. I cried in that screening.

Okay, this did not happen in my previous studio. You can laugh at gags or you can maybe feel sad. But to be moved to tears with storyboard reels? I was not prepared for that. And I worked to make that. It shouldn’t work on me. But it did. Andrew had known what he wanted to say, the man had the goods. He can pitch the entire movie by himself and hold a theater full of people in thrall. No images. Just him. A one man show. That impressed the heck out of me. After this screening I was loyal to him after that. Of course the reels will continue to have problems but we went back into that room and haggled, argued, fought and jeered at each other–all in the service of Story. It remains the most brutal Story Crew experience I’ve ever had. We cared and we were raw and not polite all the time. But we came at the problem, invested of ourselves and used that to crack this story.

Del Carmen was named head of story on Up, where he handled one of the movie’s most famous moments: when old Carl leafs through the photo album that reveals his life with his late wife Ellie. His work on this scene was informed by his personal life:

Bob [Peterson, the film’s co-director and co-writer] gave me one page that describes the moment, but this was to be wordless. This was early in the movie’s story development, so nobody knew how it was going to work. In my personal life I had

something going on in the back of my head: my father was now in a hospice and could not speak anymore. His years of being in and out of hospitals and surgery had taken its toll. He only had his face to show us if he was feeling good or not.So I’d sit on his bed and tell him I was working on a movie where the hero is an old man with a head full of white hair, just like him. He also wore dark rimmed glasses. I showed him my storyboards on my laptop. He’d see Carl and his eyes would “smile” and he’d attempt to speak but nothing would come.

I pitched him the sequence of Carl leafing through the pages of the adventure book. All the poses of his face and his eyes are the only way to say what he is thinking. Same with my dad — I tracked his eyes. His eyes told me he liked it. I used that wordless sequence to feature my father as the inspiration to tell Carl’s story where he remembers a life through pictures.

By Inside Out, del Carmen had been promoted to co-director. His fellow director was Pete Docter, whose daughter was entering adolescence at the time; the changes in her personality were on his mind. Del Carmen had been through the same experience with his children. This phase of parenthood came to inform the story’s portrayal of the emotions inside young Riley’s mind:

I had told Pete that since we chose the center of the movie to be Joy, that meant she must be just like him: a parent. One who loves unconditionally and infinitely. I went through it and did not love it, and now it appeared Pete was about to start it. He tackled the movie in the spirit of discovering his place in this uncertain phase — of telling his story as Joy, the invisible parent — and letting the world see his struggle.

Of course, we didn’t get all of that right off. We started with a hunch that Joy’s main relationship would be with Sadness. I boarded that moment early. But we got scared out of it — it was too early. After a few more screenings and reels where we pitted Joy against Fear, we realized we had to start over. And then we faced what we had before: it had to be about Sadness and Joy.

The parent role in all this is about the lament of losing your little girl when she grows up. She changes and will never come back, not in the same way. She does not return to that idyllic time when we were the center of our children’s life. We did it to our parents. Now it’s our turn. That is the heart of Joy’s story.

As he moves to Netflix, del Carmen is confident his own story will remain integral to the ones he tells.

This is what we are doomed to be: to have what we are going through in life show up in what we make. No matter what we’re making. It can feature toys come to life, invisible guardians in our heads, or what have you — but at the heart of it is the story that we are living through. Our lives are in our movies. If you’re any good at this, then this will be your curse.

I grew up somewhere else. My story starts in a group of islands, in a region that I’ve now traveled back to many times over. Each time I wish I could stay and relearn what I missed. Now I feel the pull of figuring out the beginning. The parts that I use to make movies began there. So on this new journey I go where these stories will thrive. I carried these tales to Netflix, and when they heard my story they asked me to tell it here. So this is where I’m growing and nurturing these stories that have never been told, in an arena they deserve to belong to.

At Netflix I’m inspired by all the creators and storytellers who come from all over the globe, telling tales that are windows into their own worlds which I’m so thrilled to discover. I’m hopeful about seeing how all these stories will help fuel change and bring us all a little closer to understanding each other. That’s my next threshold. I’m where I need to be.

Del Carmen’s comments have been edited for brevity. Photo at top by Deborah Coleman.

.png)