National Film Board of Canada Producers On How Animated Shorts Will Evolve In The New Decade

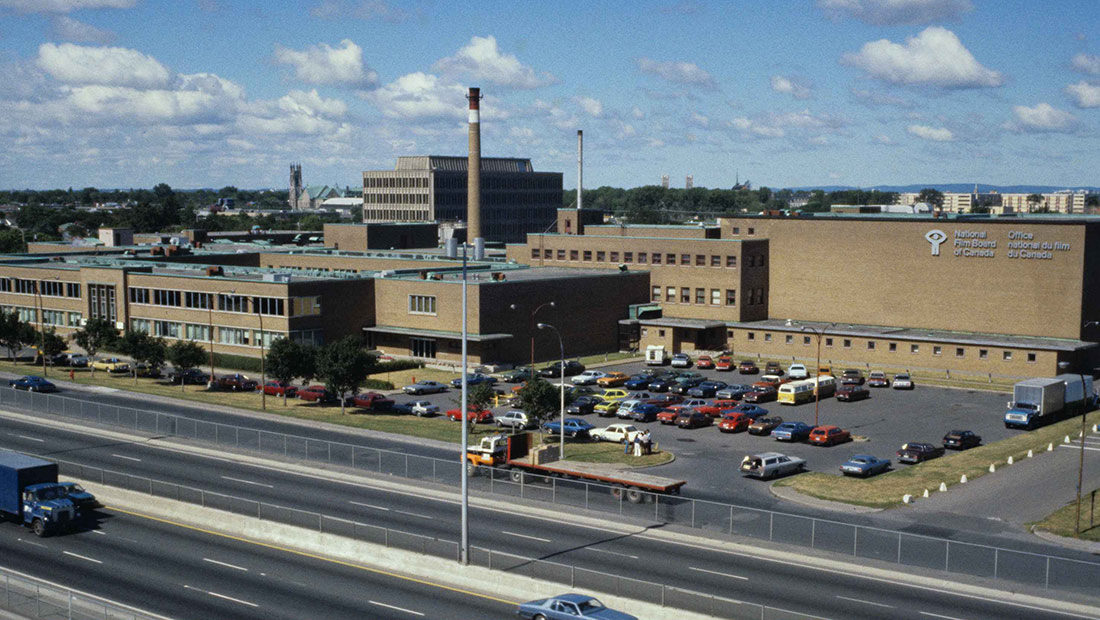

At present, the National Film Board of Canada is relocating from its fabled old studio in the Montreal suburbs to a gleaming new headquarters downtown.

The NFB’s animation division is split into two studios: the English and French programs. The studios are editorially independent, although they share staff and branding, and all their films are released bilingually. They are led respectively by Michael Fukushima and Julie Roy, who, as executive producers, determine the slates and strategic visions of their programs.

On a recent visit to the new building, I sat down with Fukushima and Roy for their first-ever joint interview, which we’ve published in two parts. In the first part, they told me what it takes to become an animation filmmaker at the NFB. Below, we discuss the recent shifts in the wider world of animated shorts and how the format is evolving as we head into the 2020s.

We’re in your brand-new offices. How will the new environment influence how you work with your filmmakers in the short term?

Julie Roy: One thing that’s different from the old building is that the English and French studios used to have separate spaces for filmmakers. Now, the spaces are intermixed, so the two communities will cohabit and work together.

Does that reflect a change in the NFB’s administrative strategy?

Roy: No. It’s about how people mingle on an everyday basis. For example, we’ll now assign spaces based on the needs of the projects: what needs to be installed, what techniques will be used, and the environment.

Michael Fukushima: You know, we went with this route of having the filmmakers mixed between the [two floors occupied by the animation division] because it’s part of what Julie and I believe should be happening — that there should be more integration, collaboration, communication between the two programs.

In all honesty, all of the French animation filmmakers are bilingual; not all of the English animation filmmakers are bilingual. Part of my goal is to compel some of the English animators to have to cohabitate in some way, communicate in some way, with their French counterparts. We had kind of a political subtext for sharing the spaces as well.

You’re now in downtown Montreal, much closer to the city’s big animation and vfx studios. Does this herald collaborations with these companies?

Fukushima: I think it will eventually. I don’t think we’ll ever be able to collaborate as creative partners, but being downtown helps introduce our filmmakers to that milieu. It gives them a chance for side gigs, other work, and other contacts. That’s great.

Once our public space is open [in the ground-level atrium], we’ll be having public events, meet-and-greets, things like that. My hope is that folks from Unreal, from game studios, will now be able to come, meet us, and see how we operate — differently, perhaps, from how they operate. I don’t think it will affect whether we partner or co-produce with them.

Just around the idea of being downtown: it’s going to be a hell of a lot easier and more desirable for the majority of our filmmaker crew to come here every day, rather than trek out to the suburbs.

Roy: I pretty much agree. You know, the NFB is really well known — and well regarded — in the international animation world. But it’s true that we have a hard time getting noticed outside the industry, even among our own Canadians. So arriving downtown in a new building bang in the middle of the cultural scene, with the big NFB logo on it — I think the greatest influence this will have is on our capacity to raise our profile.

The floors above us are occupied by the NAD–UQAC center, which is chiefly a 3d animation school. Most of their students don’t know about us, but now we’ll exist for the hundreds of students who’ll go by. And I think this could lead to collaborations with the NAD; perhaps we’ll get students to come over, or share our spaces. This could spur us on in a way that we didn’t have before.

Are you losing anything by leaving the old building for the new one?

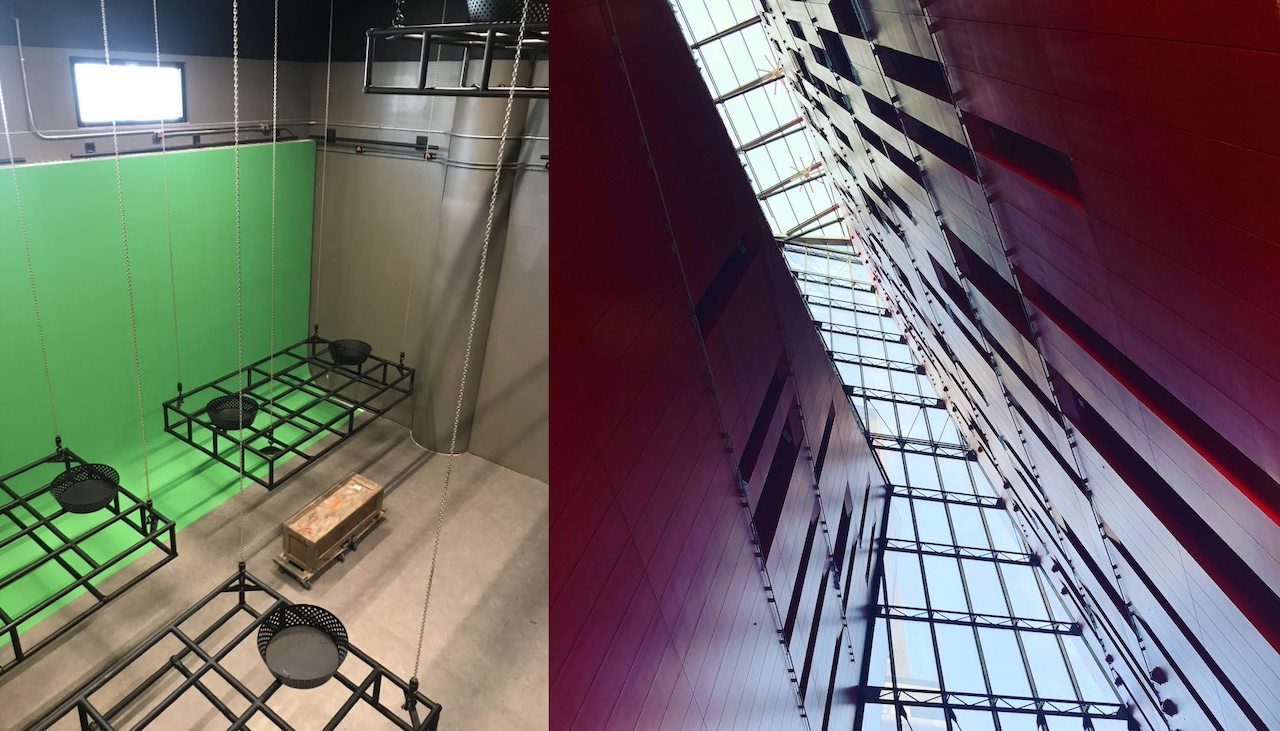

Fukushima: Ghosts! I’ve been here, either as a filmmaker or as a producer, for 30 years, so leaving the old building is definitely bittersweet for me. In truth, that building, as old and institutional as it is, was really a custom-built film studio. Every production space was designed for some kind of film production, and then the building was built around it.

The dilemma with this building is that it was designed as an architectural structure, and then our production spaces were squeezed in to fit into the space that existed, which took two years of our time. It was hard work.

Roy: I spent 25 years in the old NFB. I’ve really got no nostalgia for it — I’m very happy to be here. But I’m impatient for us to finish moving in, for all those empty rooms to be filled, for the soul of the place to come back.

I noticed that Lizzy Hobbs’s [NFB co-production] I’m OK recently premiered online while she was jurying at Ottawa International Animation Festival, which seemed deliberate. To what extent do you adapt your distribution strategy for each film?

Fukushima: There’s a lot of strategy that goes into the online launch. Short animations have no real other life after festivals, so the online life is crucial. The producer, co-producer, and director work very closely with their marketing manager and our social media team to come up with the best path, launch date, and forum for every animated film. In the case of Lizzy, once we knew that she was jurying and doing masterclasses at Ottawa, it just seemed natural to launch online then.

Roy: Strategies are devised case by case, but there’s a shift going on: the windows are shrinking. Before, films could spend two years doing festivals. Now, we try to say that they will go online after a year of festivals. Sometimes, it’s simultaneous, depending on the nature and potential of the project.

You’ve probably seen Lori Malépart-Traversy’s film The Clitoris. It’s an absolutely crazy viral hit, and that absolutely hasn’t prevented it from being selected at festivals, where it’s also a massive success. [Author’s note: Malépart-Traversy made The Clitoris outside the NFB and it premiered online in 2017 as part of Cartoon Brew’s CB Fest, but the organization is producing her next film.]

What’s certain is that when a film does well at festivals and wins prizes, it’s really hard and costly to recreate that buzz a year later for the online launch. That’s why we’re trying to shorten the windows. Putting a film online is fun, but there’s so much stuff online now. In Canada, there’s a fashionable word: “discoverability.”

That’s the main thing institutions are interested in — they don’t ask for marketing plans anymore, but for discoverability plans. So how do we stand out online? The NFB has its own website, but we have lots of partnerships with Short of the Week, Cartoon Brew — the giants of that world.

Does the fact that you’re a public organization influence your distribution strategies?

Roy: Yes, because we’re required to reach Canadians. That’s why our films are swiftly made available for free online, for the most part: they have to be given back to the Canadians who’ve “paid” for them. So, in our strategies, we prioritize Canada a lot. Then it depends on partnerships. With [tv channel] Canal+ in France, for example, they don’t permit us to distribute the film online in their territory for two years. So we geo-block for Canada, at least.

Fukushima: I’ll be honest with you here: sometimes our Canada focus is a bit of a headache for our international co-producers. They might want their film to be released at the same time as the Canadian launch, but they’ve made a deal with [Franco-German tv network] Arte or a European distributor that restricts when they can put the film online in those territories.

Roy: In Europe, the festival strategy is longer. French producers I work with don’t want the film to go online too quickly. They’re looking to make money through either tv channels or streaming. It’s true that, as a public institution, we don’t have this burden of generating revenues so much; we prioritize visibility. Our main focus is on being seen.

Short-form streaming is starting to get serious investment from Hollywood — for example, Jeffrey Katzenberg’s Quibi platform will launch next year. Will this trend influence your strategy going forward?

Fukushima: Quibi is new enough that for us it’s a wait-and-see situation. Right now, the interest [is more in] the bigger platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime. Netflix had a great success with the David Fincher series Love, Death & Robots, which was a compilation of shorts. I think, for our sales colleagues, that’s the current model they’re thinking of, in terms of revenue generation.

Roy: The NFB tried business models like a subscription-based Vimeo channel for short films. It didn’t work: we didn’t have enough content. Nobody’s going to pay to have five or ten new films per year. Hence why we came back to prioritizing visibility over revenue. But now I think the idea is to partner with the giants who have their own platforms. We’ll have to keep analyzing and see.

Distribution aside, what has been the biggest change in Canada’s independent animation scene since you became executive producers?

Fukushima: For me, it’s the digital transformation. Digital has completely changed the way animation is made and distributed. This is phenomenal. When I started, you had to film on 35mm film using an Oxberry camera. That was your only option, unless you wanted a crappy black-and-white video signal. So you needed money, an institution of some sort. Now my son can make an animated film on a tablet.

I believe this means that the role of a strong creative producer is now more important than ever, because the producer is like a sounding board, and helps the filmmaker craft a better film. And then, just in terms of dissemination, the ability to post anything you make on Youtube or any other channels — all of that has changed so dramatically.

There is almost no barrier anymore to access. I had to strike prints of my films to get them to festivals. Kids don’t have to do that anymore. They can make a Quicktime Prores file and ship it off via Wetransfer in 20 minutes.

Roy: I’ll go with a completely different point. It’s not just in Canada, but many films are now being made by women about the body and sexuality, in a completely uninhibited way. For me, that’s a remarkable shift. I did a master’s on the films of Michèle Cournoyer, who was really a pioneer in her way of approaching women’s issues. Signe Baumane and Michaela Pavlátová also went into those areas.

But today, with all the feminist movements, the post-MeToo, there’s a kind of liberation, and I’m seeing a proliferation of shorts where women feel totally at ease talking about very intimate subjects, sometimes narratively, sometimes more abstractly. Malépart-Traversy [is working on a five-part anthology film] about female masturbation called Caresses magiques [see image at top] — that’s just one example.

The NFB’s budgets have been declining for years. Recently, filmmakers publicly criticized how the organization is spending what money there is. What can you and your studios do to keep making films that reflect NFB values?

Roy: As executive producers, our role is to assemble a balanced programming slate. That balance is varied depending on what budgets are available. We’re co-producing a series called Comic Strip Chronicles with Sacrebleu Productions in France.

The idea is to try to produce both major films which cost money, and films that are shorter, and cheaper and quicker to make. For example, we’re managing to finance Canadian filmmakers in international co-productions, like Janice Nadeau and Dominic-Étienne Simard. I think it takes creativity to maintain a quantity of films while varying the production model.

Fukushima: It’s exactly the same for us. Programming choices are harder to make, because we have less money, so we have to be more rigorous, more strategic. But different forms of co-production, of partnerships, are crucial. And, honestly, keeping pressure on top management here to be aware that we need more money directed toward production. That’s also a part of my job.

Roy: Yeah.

Fukushima: There’s pressure on the president of the NFB from all directions, and I have to also be one of the people pressuring him.

The NFB/ONF Creation group will officially be included in the organization’s next round of strategic consultations…

Fukushima: It’s a good sign, yeah. I’m hopeful. I just hope the filmmakers can maintain a coherent vision and message, and not break off into 250 different conversations.

(This text has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity. Fukushima spoke in English and Roy in French; her answers have been translated).

.png)