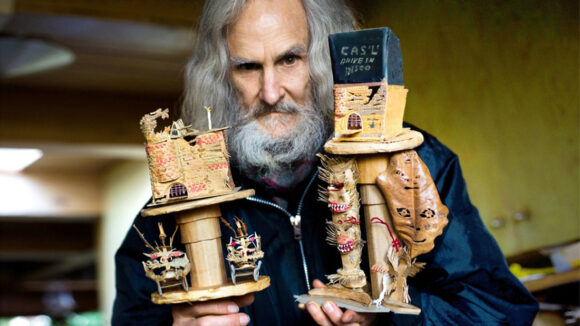

Bruce Bickford, Stop Motion Icon And Frank Zappa Collaborator, Dies At 72

It’s hard to fathom that legendary American indie animator, Bruce Bickford has passed away. He was 72 in age when he succumbed to a cardiac arrest on Monday, April 29th. Yet, in truth, Bickford never lost the essence of a child. He explored the world, seeing, feeling, and discovering the beauty, terror, and wonder of it all each day as though it were the first time.

Although Bickford achieved a cult following in the 1970s through his work for Frank Zappa, from the 1980s to his death, he worked in relative obscurity in his home in Seattle, continuing to create ingenious, baffling, and mesmerizing line and clay animation.

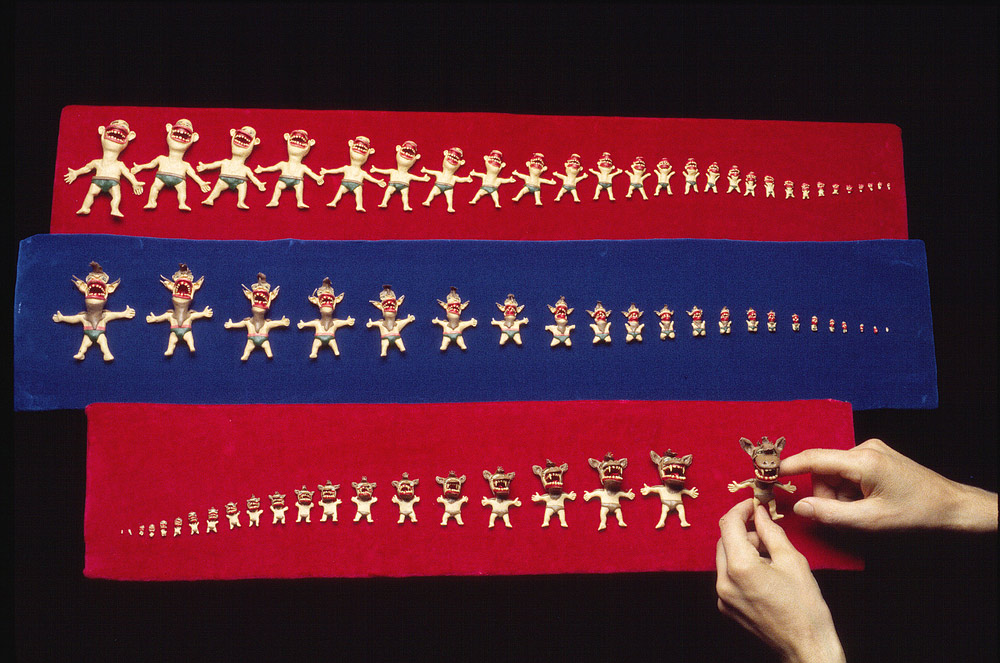

Bickford’s animation (including Baby Snakes, Prometheus Garden, The Comic That Frenches the Mind, Cas’l, Atilla) remain incomparable and indescribable. There was no one like him in animation. The closest comparison might be found in the freewheeling jazz experimentation of Ornette Coleman or Albert Ayler or the freewheeling mystic streams of James Joyce. Nothing is stable in Bickford’s universe. Heads, humans, and landscapes form, re-form, transform. It’s like watching a child blissfully lost in play with his action figures. Most of the time you don’t have a clue what the hell is going on, but you’re mesmerized by the sheer inventiveness and wonder of it all.

And Bickford’s world was never really meant to be understood; it was to be experienced, like life. As animation writer/historian Nobuaki Doi told Cartoon Brew, “Bruce’s animation films are overwhelming. They tell so many things at the same time. He doesn’t follow basic rules of animation. He makes everything move and the audience cannot keep track. It was only later when I met him that I realized that that’s how he sees the world. While we see might see one or two things happening, Bruce sees everything!”

“Bruce animates how dreams and even our darkest nightmares might feel,” writes Nicholas Garaas, a stop-motion animator who worked closely with Bickford as a manager/curator/archivist since 2015 and became one of his closest friends. “His works seamlessly bridged the gap between mesmerizing and horrifying while remaining mysteriously relevant.”

During the last decade, there was a bit of a resurgence of interest in Bickford’s work thanks to a bevy of festival appearances (e.g. Ottawa, Portland, Tokyo, Belfast) and art shows. His work resonated with a number of contemporary animators. “Whilst I was studying at Newport University, I made a film called Bluuuuurgh,” recalls British animator, Peter Millard.

One of my teachers, James Manning, told me how it reminded him a lot of this animator called Bruce Bickford and that I should go straight to the university library to rent out his dvds. I don’t say this lightly, but they changed my life. The passion, energy, confidence and uncompromised nature of his work was and still is a constant source of inspiration and assurance to my own work.”

Bickford’s influence extends beyond the animation world. Veteran actor and director Alex Winter got to know Bickford while making a forthcoming documentary about Frank Zappa. “Bickford was a tireless creative force, and an inspiration not only to other animators, but to anyone who, like myself, was deeply impacted by his singular and hugely imaginative work,” Winter told Cartoon Brew. “I feel privileged to have worked closely with Bruce over the last few years on the Frank Zappa doc, and grateful we’ll be able to share unseen work of his, from past and present, in the movie.”

Bickford was born in Seattle on February 11, 1947. One of four sons, Bickford was into arts from the start. One of the earliest cinema impressions he remembers was seeing Vittorio de Sica’s The Bicycle Thief. “The part I remember,” Bickford told me in 2015, “was when this rich kid was eating a cheese sandwich. It looked like the cheese was stretching down. The way I remember it from my childhood was that it was stretching down so much that was it coming out of the upholstery of the chair. It was almost like animation.”

The animation that had the greatest impact, surprisingly, given the complexity and seemingly non-linear layers of his own work, came from Walt Disney. “I saw Disney’s Peter Pan in 1953,” recalled Bickford. “I knew about Peter Pan through a book so I was hyped up on seeing it, but the movie itself exceeded any expectations I could have had. Whatever you say about Disney being cornball or anything like that, you’ve got to admit he was very tasteful. The colors in the movie are stunning. It was so exotic. Going to that island. Captain Hook, I thought, was fascinating. So many things about the movie. I felt like I was transported to that land. At night for the next year before I went to sleep, I’d think about that movie and make my own version of it in my mind. I always hoped that when I went to sleep I’d dream about the movie.”

It wasn’t until he saw a Ray Harryhausen movie that he started to realize that animation was something he could do. “I could move model cars around and I was playing with plastic cowboys and jungle natives and animals and stuff. I’d sit and play with them for hours, so I had that habit. I was having a bit of a crisis. I’d spend hours thinking about movies and what I was going to do with my life. In 1964, I got an 8mm camera and that’s when I started animating my model cars and making crude clay figures.”

Bickford’s artistic start was briefly put aside in the mid-1960s while he served three years in the U.S. Marines – including a stint in Vietnam where he got shot at while defending a munitions dump: “I could see tracers in the distance coming out of the jungle splitting the early morning fog apart in waves as I heard the bullets whiz past my ears…”

The experience had a long-term effect on Bickford’s life and art. One of the common themes of Bickford’s work is violence. His films are littered with bloodshed to the point where it’s sort of commonplace. While Bickford never acknowledged the traumatic impact of his brief war experience, perhaps art was an unconscious form of therapy. In 2015, I asked him where he thought the violence came from: “I don’t know. I guess I’m violent, but I don’t want to be in real life. It’s too costly. We should all just take it all out through fictional means.”

He returned to animating in 1969, exploring an assortment of techniques (line, cel, clay, stop motion). He began to get some attention with the short, Tree, and then he won his first festival award (at the 1971 Bellevue Arts Festival) with Last Battle on Flat Earth, a frenetic clay animation piece that featured the manic, hallucinatory epic violence that would dominate so much of his future work.

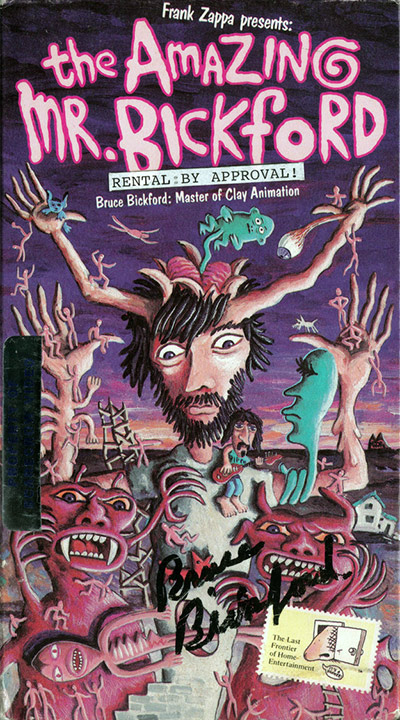

In 1973, impressed by the animation in a Frank Zappa movie, 200 Motels (1971, the animation was directed by Charles Swenson), Bickford headed to Los Angeles to meet the eccentric musician. “I went down to Los Angeles for work and I just went around town until I finally found the studio that did animation for Frank’s movie. They put me in touch with Frank’s main guy, Cal Schenkel. He arranged for me to meet Frank. Bickford impressed Zappa with some of early animation. “It was like an extended bar room scene that went on for about 15 minutes and a battle scene and some line animation,” recalled Bickford. “That initially got his interest and a year later they called me back. I eventually moved down and worked for Zappa for six-and-a-half years.”

During those years, Bickford was set up in a studio in Santa Monica and worked on two projects – A Token of His Extreme (1974) and Snake Eyes (1979) – both matching Zappa’s music with Bickford’s animation.

Working with Zappa was not easy (conversely, I’m sure working with Bickford was no picnic either). “We didn’t get along so hot,” admitted Bickford. “It was the fault of both of us. He was not good at making movies. The projects should have at least had a production manager. And I wasn’t cooperative when it came to doing what I was supposed to do. So it kinda went both ways.”

In Memoriam

The Amazing Mr. Bruce Bickford

February 11, 1947 – April 28, 2019 pic.twitter.com/nwvpQJQYHd— Frank Zappa (@zappa) April 29, 2019

In 1981, Bickford returned to Seattle and his mother’s home. Said Bickford in 2015, “I went to work in her basement and she put up with me. It would be nice to get funding, but after my parents died, I inherited the house and enough of an inheritance that if I’m frugal I can last a few years probably.”

From that time on, Bickford worked almost religiously on an assortment of projects ranging from short films (including the beautifully terrifying clay-animated classic, Prometheus Garden, in 1988) and a feature film (Cas’l, 2015) to graphic novels and unfinished scripts. He also began to get more attention on the art and festival circuit, largely stimulated by Monster Road (2004), Brett Ingram’s feature-length documentary about Bickford’s fascinating and unconventional life and work.

To the end, Bickford never lost his childhood passion for creating or animation: “Animation in my opinion is the great art form. Movies incorporate all the other arts: design, acting, writing, everything. Animation is the most dynamic thing you do in movies because it can create things that wouldn’t be photographable in real life. Things don’t just happen, you have to make them happen. To me that’s special.”

.png)