How ‘The Quinta’s Ghost’ Used VR Tools To Revive Goya’s 200-Year-Old Black Paintings Aesthetic

When Emmy-winning filmmaker James A. Castillo (Madrid Noir) set out to make The Quinta’s Ghost, he wasn’t adapting a historical anecdote. He was stepping into the mind of Francisco de Goya, trying to imagine what the painter might have seen as he created his infamous Black Paintings on the walls of his home, La Quinta del Sordo.

“I’ve always been fascinated by Goya as an artist who confronted his own demons,” Castillo says. “These paintings are so raw and personal — they feel like he was painting to survive his own fears.”

The Quinta’s Ghost, which world premiered at Tribeca this summer, is an animated horror short that re-imagines the last years of Goya’s life. In 1819, the exhausted painter retreated to the countryside to escape court politics and the noise of Madrid. But illness, isolation, and memories of Spain’s violent past haunted him. In the film, those ghosts literally arrive at his door, pushing him toward the desperate, hallucinatory art known today as the Black Paintings.

Castillo provided Cartoon Brew an exclusive video to break down how the project advanced through the stages of development and production. We spoke with several artists who worked on the film to find out how they created a VR-fueled pipeline to tell this two-century-old story.

“It’s a ghost story,” Castillo explains, “but it’s also about the creative process — the price artists pay when they face their darkest truths.”

A Small Art Department With Big Ambitions

Despite its painterly complexity, The Quinta’s Ghost was built by a surprisingly lean core art team. “It was a very small art department for the most part,” Castillo recalls. “Pakoto [Martínez], Joaquín [Martínez], and I constituted the core team. We were the ones filtering everything to make sure that the style and look of the film preserved a sense of consistency.”

Around this trio, a “satellite” group of artists joined at different stages. “Jaime Posadas and Estefania Pantoja did the majority of the work creating the house—its layout, designs, and props,” Castillo says. “On the other hand, Alfonso Salazar and Kellan Jett came to help set up the palette and atmosphere of the film.” At the busiest point, about 40 artists were contributing across design, animation, modeling, and rigging.

According to the director, the most challenging task his team faced during production was finding and maintaining a consistent tone across the film’s various departments.

“Each discipline interprets tone differently,” Castillo notes. “In design, we were maximalists — we needed texture, shape language, color palettes, lighting. But in animation, we needed minimalism: nuanced performances, slow movements, stillness. Keeping everyone rowing in the same direction meant constant briefings, detailed documentation, and cross-department tests. We’d show shading tests to animators, animation tests to sound designers so that everyone could feel the same film.”

Goya’s Legacy, Through New Eyes

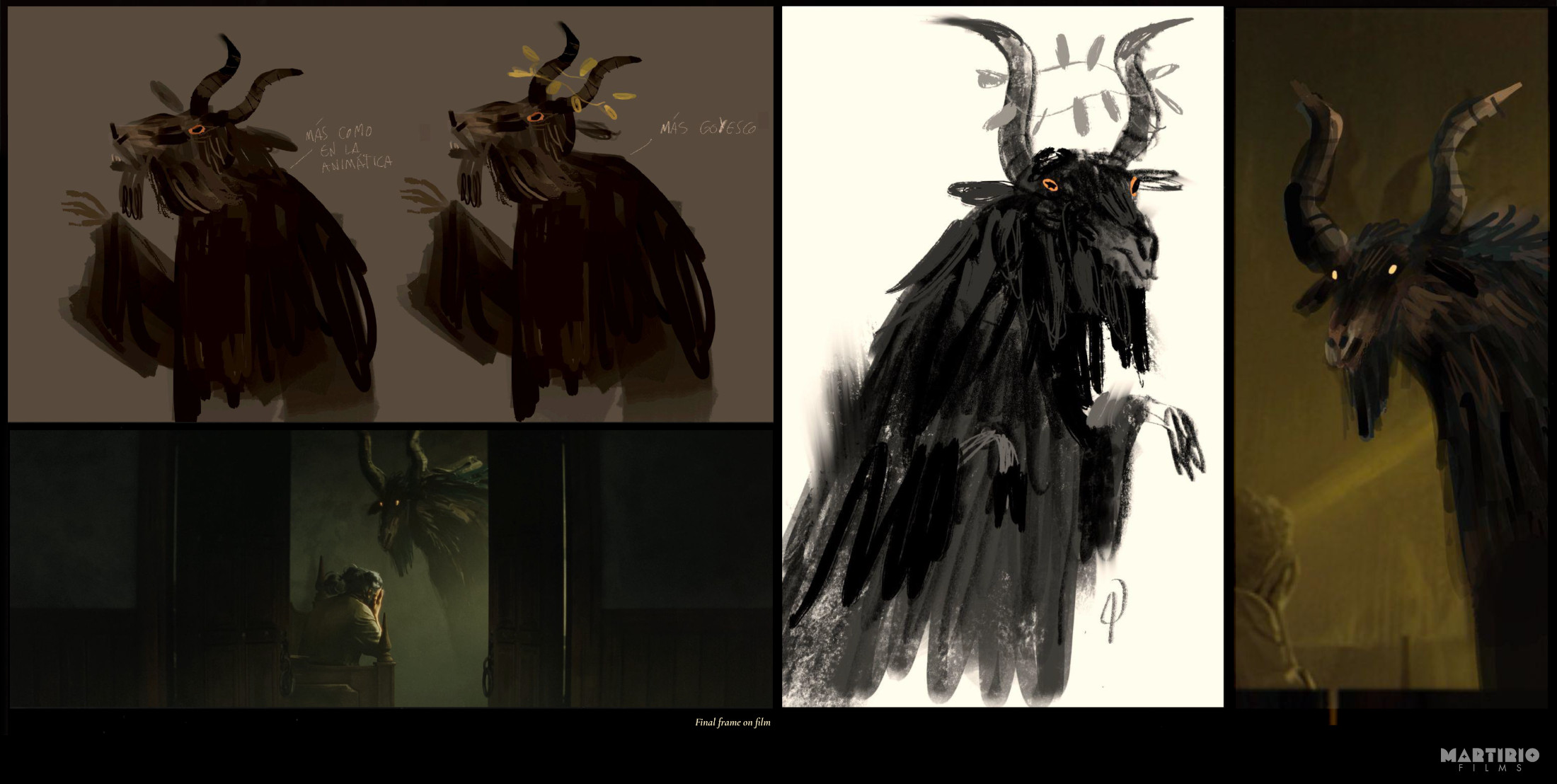

Lead designer Pakoto (The Book of Life, Maya and the Three), known for his visceral, abstract style, faced the tricky task of channeling Goya without imitating him.

“It wasn’t easy,” he says. “It took a lot of study and trial and error. In fact, after almost a year of development, I realized I hadn’t really understood the Black Paintings and decided to start over.”

The goal was to create ghosts that felt born of Goya’s world but were original characters in their own right. “Painting ghosts with my style, but ones that reminded you of Goya and also fit into James’s short film, was a big challenge,” he admits. “Once we found that style, bringing it into 3D was another challenge, but Joaquín is a genius, one of those Renaissance-type artists who can paint, animate, sculpt, and do everything well… His mastery with VR painting made those ghosts come alive.”

A VR Breakthrough

That’s where Joaquín, the film’s VR artist and modeler, stepped in. He used Quill, a virtual reality painting and modeling tool, to sculpt and texture the ghosts in an entirely new way.

“Quill lets you paint strokes as geometry with pure colors, simulating light in a painterly way,” Joaquín explains. “It’s not painting, and it’s not modeling, it’s something in between, which was perfect for bringing the ‘ghosts’ of Goya’s Black Paintings to life.”

But translating Pakoto’s loose, expressive brushwork wasn’t straightforward. “His style is super visceral and breaks perspective in wild ways,” Joaquín says. “At first, I tried to replicate every brushstroke, but it felt stiff. Eventually, I learned to be looser, to fill areas more freely so it stayed true to the original feeling.”

Sometimes he built relief-style sculptures instead of full 360° models. “Because the camera didn’t need to show every angle, I could focus on what mattered for the shot,” he explains. Once sculpted in Quill, the characters moved to Blender for rigging, blend shapes, and controlled animation tweaks. “It was an experimental workflow, a little weird for a traditional pipeline,” Joaquín admits, “but it simplified things. I could solve creative traps myself until it looked good on camera.”

For him, the experiment was worth it. “I’m convinced Quill is a powerful tool, especially for visual development. Combined with Blender, you can do amazing things, even if you don’t have a huge team.”

Illusorium: Building a Pipeline for the Unknown

Spanish studio Illusorium handled the heavy lifting of turning Castillo’s vision into a scalable production. This was their first fully original narrative project, and integrating VR assets was new territory.

“We were excited, but also aware of the responsibility,” the producers recall. “James and Pakoto had spent so much time perfecting the style, and Joaquín translated it impeccably into 3D. We didn’t want to be the weak link.”

VR integration was the big technical hurdle. “We experimented a lot before finding the perfect look and testing it on key shots,” they explain. “Once we nailed that, we built a reasonable pipeline to produce the remaining scenes containing Quill geometry. It was a challenge, but the result surprised all of us.”

Crucially, the process proved repeatable. “For pure animation, the workflow is totally scalable,” they say. “We simplified tedious steps and learned how to integrate experimental tools like VR without breaking production. It gives us confidence for future original projects.”

Illusorium also relished being part of the storytelling from day one. “Usually, service work keeps you in your comfort zone. Here, we were helping shape an IP from the start. That motivation was huge.”

Lessons From the Ghosts

For Castillo, the production reinforced a core belief: trust your artists. “As clear as your vision is, you have to let the artists be artists,” he says. “Set boundaries but trust their instincts, even when you can’t picture the outcome yourself.”

He cites the ghosts as an example. “I had a theoretical idea, but no idea how to implement it. I trusted Pakoto, Joaquín, and Illusorium. It felt weird at first, but it paid off; the final ghosts are something I couldn’t have imagined alone.”

Pushing Spanish Animation to New Places

The Quinta’s Ghost is the first production of Martirio Films, Castillo’s independent studio aimed at blending auteur animation with genre storytelling. “I want animation to break generational and disciplinary boundaries,” he says. “We’re building a place for bold voices to tell universal stories.”

For Illusorium, it’s also a milestone. “Our DNA is about exploring new styles,” they say. “Projects like this push us beyond comfort zones and show what’s possible.”

At its heart, though, the film belongs to Goya’s spirit. “Goya painted to exorcise his ghosts,” he says. “We just gave those ghosts a stage and let them dance in VR.”

.png)