The Making Of Natalia Mirzoyan’s ‘Winter In March,’ An Oscar-Qualified Short Telling A Personal Story Of Resistance

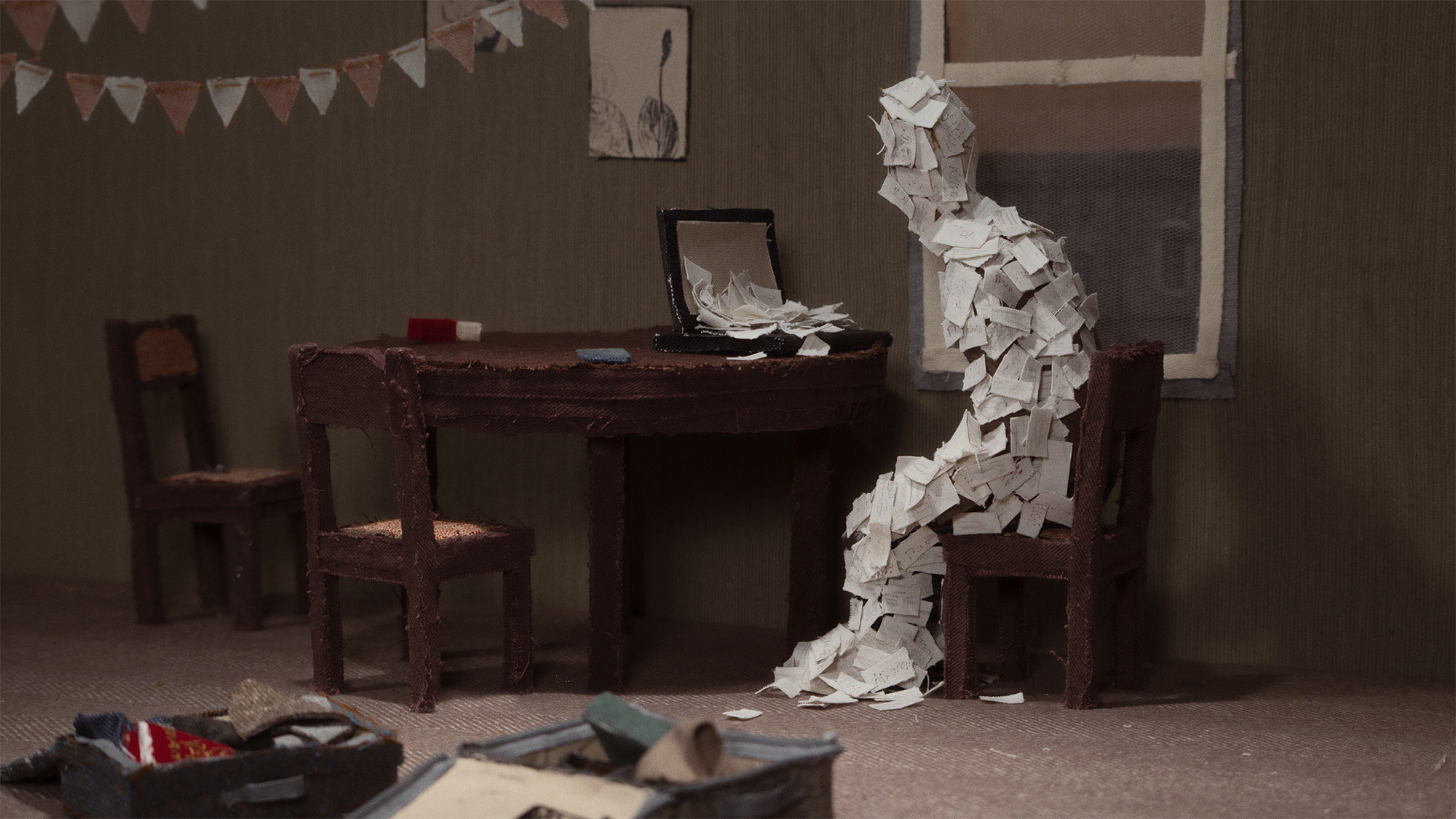

Winter in March is a handcrafted film that uses soft materials to explore difficult, often painful subjects. Director and writer Natalia Mirzoyan has called it “a documentary road movie.” Though based on real events experienced by Mirzoyan’s friends and her own family, the film distorts reality into a dreamlike, surreal experience, blending nightmares and anxieties with recent history.

Opening on a young Russian couple, the film follows Dasha and Kirill, on the morning their country launches its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Shocked and appalled, they struggle to comprehend the unfolding events.

While Kirill becomes paralyzed by anxiety, Dasha tries to join protests against the war and the regime. But the protests are quickly suppressed, and Kirill’s mental state worsens. Feeling helpless and saddened, the couple decides to pack their belongings and leave their country for good. On their route to Georgia, Kirill falls deeper into depression, while Dasha remains determined to get them both out of Russia safely. The metaphorical cold of the Russian winter lingers behind them as they experience Kafkaesque encounters at border checkpoints.

Winter in March premiered in May 2025 at the Festival de Cannes, in the La Cinef section, finishing in third place (ex aequo). The film later won an Oscar-qualifying Best Short Film award at the Sarajevo Film Festival and was recently selected as a European Film Awards 2027 Short Film Candidate. Since May, it has received more than ten notable international awards.

The Story and Message

From the outset, the filmmakers behind Winter in March recognized that the experiences of a couple escaping an oppressive regime cannot be compared with the suffering of people being invaded by that same regime. After all, what are anxiety, uncertainty, and uncomfortable circumstances compared to the bombings, killings, and torture endured by the people of Ukraine?

Even so, the message of Winter in March felt important to them: voices of opposition and peace — voices that may one day help influence change from within aggressor states — also have weight and should be heard.

The film’s composer, Evgeny Fedorov of the Russian alternative rock band Tequilajazzz, had to leave Russia after publicly opposing the war and the political regime. After receiving threats against his life, he fled through the Estonian border just weeks into the invasion. Estonia granted him political refugee status. The collaboration between Natalia and Evgeny adds additional layers to Winter in March and reinforces its themes of resistance, individual agency, and peace.

Evgeny hopes the film will reach others who oppose the dictatorial oppression and aggressive behavior of their countries. Natalia admits that when she began working on Winter in March, she hoped the war would be over by the time the film was completed. Sadly, that hope did not materialize, and the war continues today.

With regret, she notes that the film now resonates with even more viewers worldwide, who perceive echoes of their own socio-political realities. As democracies struggle around the globe, people find recognition and solace in the film’s message. She hopes that freedom will endure, that human rights issues will receive the attention they urgently need, and that the people of Ukraine will soon know peace again.

Production and Collaboration

Natalia Mirzoyan had already established herself as an award-winning filmmaker — best known for her 2018 short Five Minutes to Sea — before making Winter in March. Originally from Armenia, she lived and worked in Saint Petersburg until the full-scale invasion of Ukraine began. Like the protagonists of her film, she left Russia in the spring of 2022. She settled in Estonia and, as a long-time admirer of Estonian stop-motion animation, pursued a master’s degree at the Estonian Academy of Arts.

Winter in March is her first puppet stop-motion film and began as her graduation project. Natalia learned puppet-making under the mentorship of Anu-Laura Tuttelberg.

Ülo Pikkov, head of the Estonian Academy of Arts’ animation department, saw the film’s potential and approached Estonian animation studio Rebel Frame with the idea of producing Winter in March professionally. This led to a collaboration between Rebel Frame, the Estonian Academy of Arts, and Armenia’s ArtStep-Studio, later joined by co-producers from France and Belgium.

Metaphors and Symbolism

The decision to use fabric and cotton was deliberate. The fragility of fabric — how it tears or unravels — symbolizes the strained mental state of people who feel powerless to change decisions made by their government, such as waging war on another country. In Russian slang, vatnik — literally “made of cotton” — refers to stubborn supporters of the oppressive regime. In American history, cotton carries its own symbolic associations, evoking the legacy of slavery and systemic oppression.

Ice, snow, and cold also play significant symbolic roles. They reflect the protagonists’ deepening anxiety as they realize they have no choice but to abandon their home and country.

A recurring scene shows Dasha slowly sinking into the snow, as the inevitability and helplessness of their situation take hold.

The creators of Winter in March can only hope that the coldness of today’s geopolitical climate will eventually pass — just as even the harshest Russian winter always gives way to spring.

.png)