‘Mouse in Transition’: And Then There Was…Ken! (Chapter 4)

New chapters of Mouse in Transition are published on Cartoon Brew. It is the story of Disney Feature Animation—from the Nine Old Men to the coming of Jeffrey Katzenberg. Ten lost years of Walt Disney Production’s animation studio, through the eyes of a green animation writer. Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg. Since 1989, Hulett has served as the business representative of the Animation Guild, Local 839 IATSE, a labor organization which represents Los Angeles-based animation artists, writers and technicians.

Chapter 1: Disney’s Newest Hire

Chapter 2: Larry Clemmons

Chapter 3: The Disney Animation Story Crew

Chapter 4: And Then There Was…Ken!

Chapter 5: The Marathon Meetings of Woolie Reitherman

Chapter 6: Detour into Disney History

Chapter 7: When Everyone Left Disney

Chapter 8: Mickey Rooney, Pearl Bailey and Kurt Russell

Chapter 9: The CalArts Brigade Arrives

Chapter 10: Cauldron of Confusion

Chapter 11: Rodent Detectives and Studio Strikes

Chapter 12: Disney Dead-Ends & Lucrative Mexican Caterpillars

Chapter 13: Basil Kicks Into High Gear

Chapter 14: “Call Us Mike and Frank”

Chapter 15: The Arrival of Jeffrey Katzenberg

Chapter 16: A Gong Show with Eisner and Katzenberg

Chapter 17: The Trials of Oliver & Company

Chapter 18: Goodbye Disney

I was back in Don Duckwall’s office, exchanging insincere smiles with him. I had been on The Fox and the Hound with Larry Clemmons, Woolie Reitherman, and everybody else for half a year. But now Don wanted me to go on another assignment.

“Ken Anderson is working on a project based on a book called Catfish Bend,” Don said. “He needs a writer. I thought this would be a good chance for you to show us what you can do.”

SEE ALSO: Never-Before-Seen Private Photos of Walt Partying—And Performing Surgery on an Orange

SEE ALSO: Never-Before-Seen Private Photos of Walt Partying—And Performing Surgery on an Orange

I wasn’t keen to leave the “A” feature in the midst of production, but after eight months of employment I knew it was a better career strategy to do what I was told and go where I was kicked than to argue. So I widened my phony smile.

“Sounds like a fun project, Don. I would love to do it.”

“Good,” Don said. “You’ll start on Catfish Monday morning. Go down and meet Ken. Let him show you the work he’s already done.”

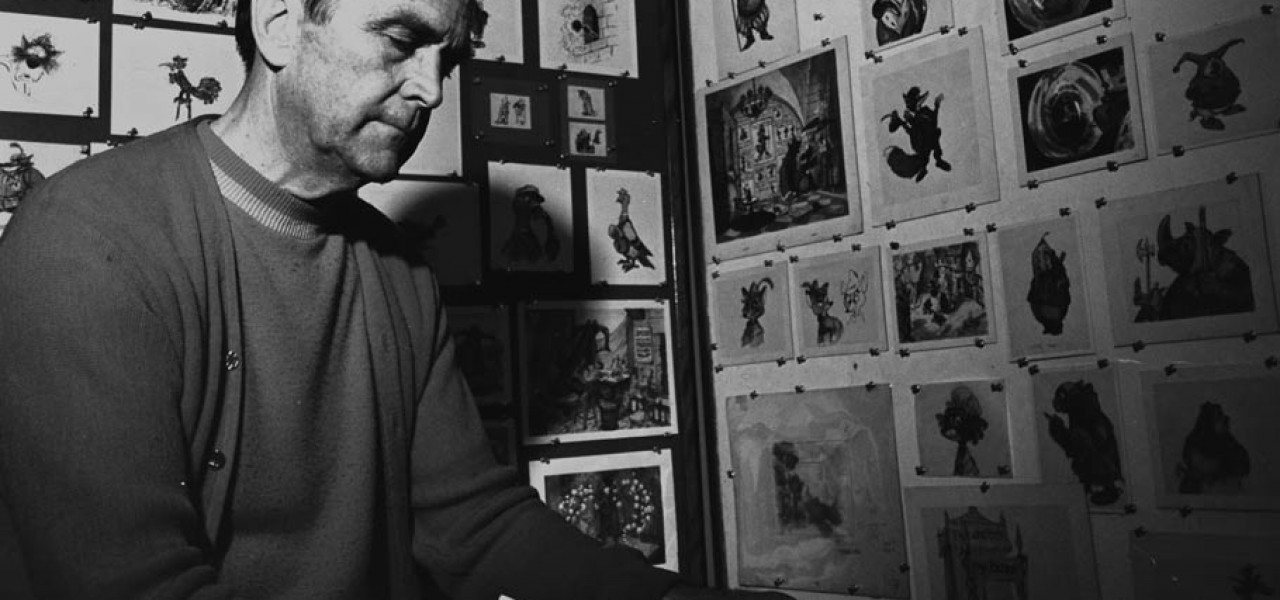

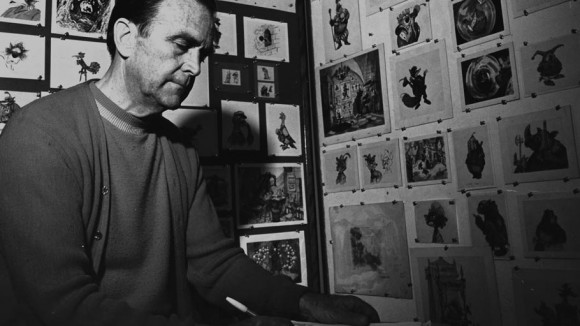

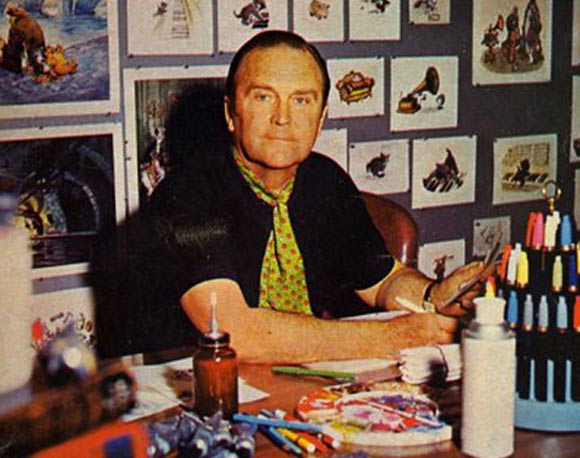

I repaired promptly to Ken Anderson’s large, airy office on the second floor of the Animation building. Ken had been busy since the conclusion of his design stint on Pete’s Dragon, which was only now wrapping up animation. He had several storyboards hanging around the room, each decorated with elaborate story sketches. There were smaller boards with some of Ken’s past triumphs: character designs from Robin Hood, scene setups for The Rescuers, all of them beautifully drawn.

Ken had been at the studio since the early 1930s. A layout artist on shorts and Pinocchio he had risen through the ranks until, as the art director on 101 Dalmatians, he had broken new ground on the look and feel of Disney animated features. There was no question that Ken owned a long and distinguished Disney career. When it came to talent, he was a force of nature inside Disney Feature Animation.

And now I was seated in one of his curved leather chairs, smiling up at him as he pointed out details about his design sketches. He offered me hot tea and I accepted. Then he showed me three “story beat” boards he had conjured from the Catfish Bend novels.

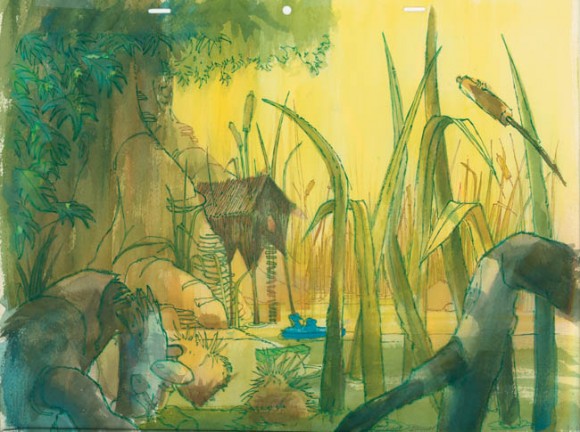

It turned out there wasn’t just one Catfish Bend book, but three. They were populated with eccentric characters akin to Bre’r Rabbit, Bre’r Fox, and Bre’r Bear in Song of the South. All the characters were swamp and river critters living along the banks of the Mississippi: a raccoon, rabbits, turtles and snakes.

Ken had visualized long sections of the Bend stories, building a rough continuity from various episodes out of the novels. There was lots of good stuff, also lot of repetitive and unfocused stuff. But he described all of it to me with relish, ending with: “Steve, you and I are going to develop a feature so rich, so compelling, that the studio will have to put the picture into production. The company won’t have any CHOICE but to greenlight it.”

I said it all sounded great, and that I was eager to work with him on the project. Ken’s bright blue eyes drilled into me.

“Wonderful. But you have to agree to one thing. You can’t breathe a WORD of what we’re doing here to Woolie.”

I blinked at him. “Woolie Reitherman?”

“Woolie wants to get his hands on everything that’s going on in the department. EVERYTHING. We can’t let him have this feature.”

An image of Captain Queeg rolling his steel balls flashed briefly before my eyes, but I repressed it. I told Ken I would keep our forthcoming development top secret. Then I hurried away from there.

My next stop was Pete Young’s room. I told him I had been taken off The Fox and the Hound to work with Ken Anderson on a project titled Catfish Bend. Pete’s eyes lit up.

“Good old Ken. Vance and I boarded sequences of Pete’s Dragon with him.”

“How did that go?”

“If he offers you tea, tell him ‘No thanks.'”

The back of my neck prickled. “Why’s that?”

“Because then you owe him. And you don’t want to owe him.”

Pete declined to tell me any more. I went away bemused. In the main hallway I encountered Vance Gerry, and told him about my pairing up with Ken Anderson.

“Good old Ken,” Vance said. “He’s a good artist. Hard working. I think you’ll have an interesting time with him.”

I nodded. Waited for more.

There wasn’t any more.

Returning to my third floor broom closet, I decided there were perhaps bits of useful information I wasn’t getting.

The next Monday I was back in Ken’s office, notebook in hand, ready to go to work. We went through his boards again, in greater detail. The lead was a raccoon who was a preacher type, and he was leading a small band of river animals through a terrible flood on the lower Mississippi. There was action, there was adventure, and there were three sets of villains: sneering city rats, loathsome river rats, and slinking, hissing weasels. They all had long snouts and were thin and ropey, not unlike the weasels in Disney’s adaptation of The Wind in the Willows.

Ken gave me his “We’ll create a rich and compelling movie that will wow everybody” speech again, and handed me a bulky treatment he had cut and pasted out of the books. He then sent me off to craft a new treatment, one that would sell the studio on the brilliance of the project. (Sadly, his treatment hadn’t achieved this goal.)

Over the next several weeks, I read the books, digested Ken’s treatment and the photostats of his boards, and turned out new pages which I dutifully showed to Mr. Anderson. I soon became aware that he was smiling and enthusiastic when I stayed close to the treatment he had previously hammered out, but dour and monosyllabic when I deviated from his text.

Along about week four on the project, Ben Lucien Burman, author of the Catfish Bend books, showed up at the studio. He was a small, thin, elderly man who was pleased that the House of Mouse was transforming his books into an animated feature. Ken and I posed with him for publicity photographs in front of Ken’s storyboards. Ken’s face was a wreath of smiles.

“Mr. Burman? We love your books. And we’re going to make a movie from them that is so rich, so compelling, that that the studio will be eager to make it.” (This was a sales pitch I had heard more than a couple of times before.)…,”

After Mr. Burman left, Ken’s good humor continued. He sat down with his tea—I declined to have any—and told me about his single darkest day at the studio:

It was during World War II. Walt was very busy running from one project to another, checking on the shorts and government work going on. Walt always had a cigarette, and he came to a story meeting holding an unlit one. I had a new butane lighter and I flipped it open to give Walt a light. Just as he was putting the cigarette up to his face, the flame sprang out. The flare was huge and it burned half of Walt’s moustache off. He yelled ‘What are you DOING?,’ and ran out of the room. Our meeting broke up before it started.

I felt horrible. I went back to my office and tried to work, but word got around about what had happened. Every time I came out of my room, people avoided me, wouldn’t look at me. That went on for days. I was sure I’d be fired.

But then, at the end of the week, Walt came over to my table in the commissary and showed me that he had cut his whole moustache off. And then he sat down and ate lunch with me.

People started talking to me again. Nobody avoided me. And everything was all right.

Sadly, things weren’t all right with Catfish Bend. As time wore on, it became more and more obvious that we had too much story and way too many villains. In looks and temperament, the weasels were like the river rats, who were remarkably similar to the city rats.

Trouble was, Ken had plucked each set of villains out of a different Burman book, and he loved all of them the way a mother hen loves her eggs. One afternoon when I broached the subject of combining the three groups into one unit of evil-doers that we could weave through the various episodes, Ken got a sour look. “I don’t know about that, Steve. I don’t know about that at all.”

“Just let me try it, okay?” I pleaded. “We won’t have to introduce and set up three sets of bad guys, just one. It’ll save us screen time.”

Ken was still dubious, but I hiked back to my broom-closet to work on a story that would show him how well it could work. For the next seven days I cut, rewrote and streamlined Ken’s bulky treatment so that his “rich, compelling” animated feature would slim down to ninety minutes from its current Gone With the Wind running time.

On day eight I took my new pages down to Mr. Anderson, and he read them. And a couple of hours later, he called me downstairs. He asked me to sit in one of the office chairs, and paced before me.

“Steve, I don’t know what you’re doing here. You’ve changed my story around. You cut some of my best characters. You … you obviously have something against me …” He stopped pacing. Leaned down in front of me, blue eyes bright with anger. “Because I know I have something against YOU!”

For half a second I thought he was going to slug me. Or strangle me. I pressed deeper into the cushioned chair.

“You … you don’t like it, Ken, I … I’ll change it! Put the characters back! I’ll rework the story. Do whatever you want.”

I didn’t know why Ken was so set on having so many different bad guys, but I had suspected he was attached to them, and now I had solid proof: Don’t change anything, you young asshole! I also knew imminent termination was glaring in my face.

I scuttled back to my office and started yet another treatment, reinserting Ken’s three gangs of villains. Then I rebuilt all the twists and turns of Ken’s expansive, over-complicated plot. While I was in the middle of the new revamp, I got a call from Don Duckwall. He wanted to see me in his office.

Shit.

As I feared, Don wasn’t jovial and smiling this time. He had me sit down and got right to the point: “It isn’t working with you and Ken. He’s talked to me and complained about you. So we’re putting you back on The Fox and the Hound.

I was depressed, but not really surprised. Ken resented anybody who attempted surgery on his baby, no matter how overgrown and misshapen the infant. I was the interloper. Ken was the angry, self-righteous mother.

But there wasn’t much I could do about that now. I visited Mr. Anderson and let him know I had been taken off his project and reassigned to Fox. His reaction startled me. He seemed surprised and a little upset.

“They can’t DO this to me! I NEED you! I need to get this story done!”

He asked if I could keep working with him, after hours, on a voluntary basis. For no extra pay. I thought it was against studio (and union) rules, but I said I would give it a try. He beamed.

“You’ll do it? Wonderful! I could really use the help. I want to keep the picture going. THANK you.”

It wasn’t an ideal solution, but I wasn’t leaving poor old Ken in the lurch, wasn’t deserting him. I felt pretty good about this until I told Pete Young about it and he kicked sense into my empty head.

“You’ve got no freaking idea what’s going on, Hulett. Ken went up to Don Duckwall a couple days ago and tried to get you fired. He was angry you were changing what he’d done. Ken always gets angry when somebody changes his stuff. He screamed at the writer on Pete’s Dragon all the time, called him names and was really insulting. He did to you what he does to everybody.”

I didn’t know who Pete had talked to, but his network of spies and stoolies was extensive. So I didn’t doubt for a millisecond that Ken had tried to get me canned. My stomach knotted.

“I … told Ken I would keep working on Catfish Bend,” I stammered. “After hours. Off the clock.”

“That’s stupid,” Pete said. “Especially since Ken told Don you should be fired.”

Stupid seemed to be my middle name, maybe even my first.

After lunch I saw Vance Gerry and went through the same “Adventures with Ken Anderson” story I had shared with Pete. He sighed and shook his head.

“Ken can be … ahm … difficult. I saw him on the phone once, yelling at Don Duckwall that Woolie was his enemy. Ken can be … emotional.”

“How about irrational?” I offered.

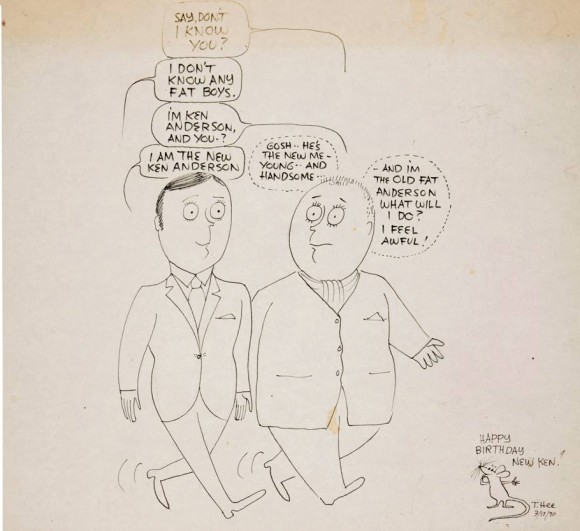

“That, too,” Vance said. “But you need to understand that Ken is a frustrated guy. Walt never liked the Xerox look of Dalmatians, and Ken, being the art director, brooded about that. And years ago, he was overseeing a story about Chanticleer, the French rooster. There was a big presentation with Ken’s drawings. Songs had been written for it, and there were a lot of storyboards. Walt sat through the whole pitch, and at the end of it he shot the project down. He just didn’t think there was enough warmth with chicken characters. Ken took the rejection hard. He shut himself up in his office. Took time off from the studio.”

“So that’s why he’s doing this to me?” I said.

Vance shrugged. “He’s never gotten to be a director, calling the shots. And he wants that, a lot. Did I mention he’s a frustrated guy?”

Ken was also, I decided, a fourteen-karat prick.

The following day I hiked down to Mr. Anderson’s lair and informed him that, on second thought, I couldn’t work on his project after all. He looked disappointed. I was glad.

Catfish Bend was never greenlit for production, and never got close. Disney dropped its option on the books, and Ken Anderson retired three months later.

After Ken hung it up, I had the opportunity to ask Ward Kimball why he had behaved so badly, why he had tried to get me fired. Ward had a different take than Vance did. “Ken’s always been paranoid, and a backstabber. In 1934 when he was a new trainee, he’d get red in the face and fall down if he thought somebody was going around him.”

So there it was. For almost half a century, Ken Anderson had been a model of consistency, fighting off all rivals both real and imagined. He might have tried to get me fired, but at least he didn’t play favorites.

.png)