When Animation Work Slowed, ‘Animaniacs’ Showrunner Gabe Swarr Built His Own Game Studio

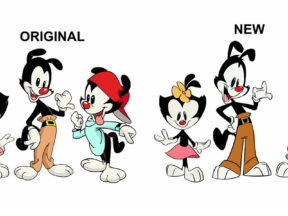

Like many animation veterans navigating a tough job market, Gabe Swarr has been using his downtime to build something of his own. The Animaniacs and El Tigre vet has spent the last few years pivoting from animation to game development, forming his own indie studio, Gabboco Games, and releasing small, handcrafted titles.

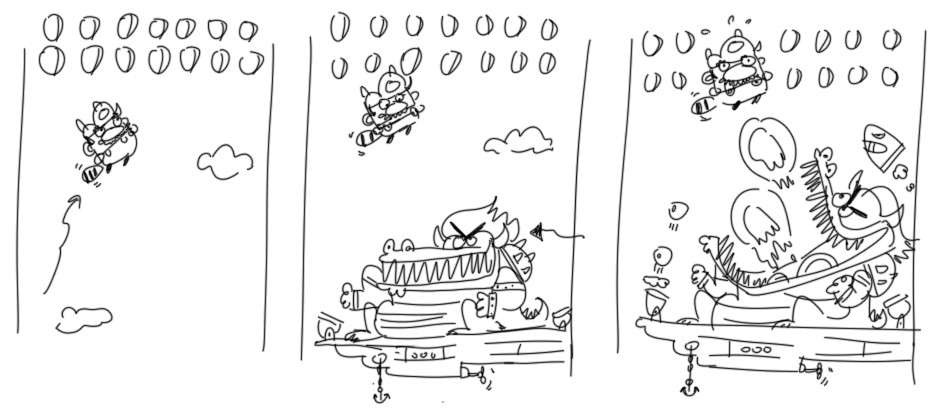

His latest project, Mario Jumpcade, was created for iam8bit’s 20th Anniversary Art Show this weekend and is both a game and a piece of art: a playable Mario-inspired experience that ties into an exclusive print and giveaway piece for the event.

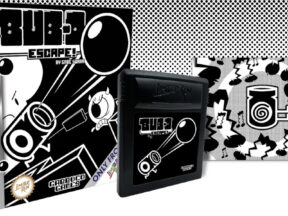

“I’ve been trying to get a game out every year for the last five years,” Swarr says. “The first two were Game Boy Advance games, then I did one for the Playdate — that little system with the crank. After that I started building for consoles. Even a small-budget game is hard to get funded, but I just keep making them. If I’m not working full-time in animation, I’m investing in myself.”

View this post on Instagram

Swarr’s latest game was developed in about 40 working days — a sprint that began after a licensing deal for another project suddenly collapsed. “I had this really good, fully animated demo that was dead in the water when the rights fell apart,” he explains. “So when I found out about the iam8bit show three months ago, I decided to jump in and make something totally new.”

Swarr says the project has sparked a lot of conversations about how artists reinterpret established characters and what it means when fans build on existing IP. “I think this ties into Nintendo’s bigger shift toward being an entertainment company,” he says. “They’re expanding beyond just games and hardware, and I think projects like this show how much cultural reach these characters have.”

Swarr built the game in GameMaker, coding most of the systems himself and designing the art in Flash. “I’m a big Flash person,” he says. “It’s perfect for setting up high-res assets and symbols, just like animation. The more modular you make things, the faster you get — it’s like reusing backgrounds in TV animation.”

That efficiency is part of a deliberate creative strategy. As a solo developer, Swarr keeps his scope small: short, arcade-style projects built around satisfying movement and tactile feedback. “Scope is defined by time,” he explains. “A 20-hour game would take three years for one person, and I don’t have the money for that. I like smaller, twitchy games — more about feel than story. My goal is to form a small studio with friends, make games, pay the bills, and have fun.”

That emphasis on “feel” comes directly from his animation background. “I know how to get a certain emotion out of movement — people see the main poses, but they feel everything else,” he says. “In games, when you combine that animation feel with game feel, you get something special. There’s no anticipation like in film or TV; when you press the button, you want an instant reaction.”

For Swarr, the connection between animation and games isn’t just stylistic, it’s structural. “You can even build a studio on revenue share, which doesn’t really exist in animation,” Swarr says. “I look at small game studios that release a bunch of titles every year. If one hits, it funds the rest. That’s the model I’m following.”

He’s also documenting his development process on YouTube, sharing the ups and downs in real time. “People love the drama when stuff doesn’t work,” he admits. “Every project has that ‘I hate this’ phase, and that’s the emotional arc of making a game. I want to show the human side of creation. not just a polished trailer, but the inspiration, the mistakes, all of it. That’s how you build community.”

Swarr plans to release the Mario project on Itch.io after the iam8bit show, alongside four other small games currently in production. “I’m doing a lot of housework, making old projects modular and ready to go,” he says. “Eventually, I want to build a library of my own IP. The only thing you really need now to make a game is time.”

For Swarr, the convergence of animation and games feels like a natural evolution. “A lot of animation people play games but don’t think they can make one,” he says. “But it’s totally possible now. The tools are there, the communities are there, it’s never been more accessible.”

.png)